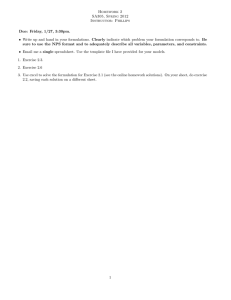

The Limits of Expanded Choice - Berkeley Law Scholarship

advertisement