To LIFT or to Flap? Which Surgery to Perform Following Seton

advertisement

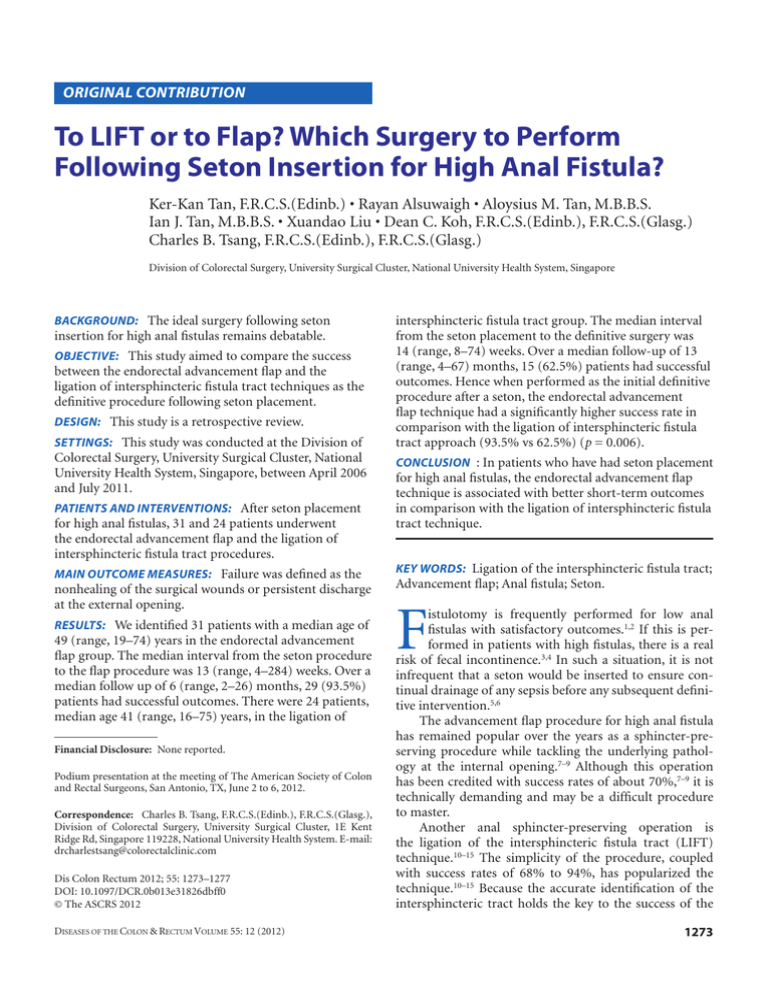

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION To LIFT or to Flap? Which Surgery to Perform Following Seton Insertion for High Anal Fistula? Ker-Kan Tan, F.R.C.S.(Edinb.) • Rayan Alsuwaigh • Aloysius M. Tan, M.B.B.S. Ian J. Tan, M.B.B.S. • Xuandao Liu • Dean C. Koh, F.R.C.S.(Edinb.), F.R.C.S.(Glasg.) Charles B. Tsang, F.R.C.S.(Edinb.), F.R.C.S.(Glasg.) Division of Colorectal Surgery, University Surgical Cluster, National University Health System, Singapore BACKGROUND: The ideal surgery following seton insertion for high anal fistulas remains debatable. OBJECTIVE: This study aimed to compare the success between the endorectal advancement flap and the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract techniques as the definitive procedure following seton placement. DESIGN: This study is a retrospective review. SETTINGS: This study was conducted at the Division of Colorectal Surgery, University Surgical Cluster, National University Health System, Singapore, between April 2006 and July 2011. PATIENTS AND INTERVENTIONS: After seton placement for high anal fistulas, 31 and 24 patients underwent the endorectal advancement flap and the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract procedures. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Failure was defined as the nonhealing of the surgical wounds or persistent discharge at the external opening. RESULTS: We identified 31 patients with a median age of 49 (range, 19–74) years in the endorectal advancement flap group. The median interval from the seton procedure to the flap procedure was 13 (range, 4–284) weeks. Over a median follow up of 6 (range, 2–26) months, 29 (93.5%) patients had successful outcomes. There were 24 patients, median age 41 (range, 16–75) years, in the ligation of Financial Disclosure: None reported. Podium presentation at the meeting of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, San Antonio, TX, June 2 to 6, 2012. Correspondence: Charles B. Tsang, F.R.C.S.(Edinb.), F.R.C.S.(Glasg.), Division of Colorectal Surgery, University Surgical Cluster, 1E Kent Ridge Rd, Singapore 119228, National University Health System. E-mail: drcharlestsang@colorectalclinic.com Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 1273–1277 DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826dbff0 © The ASCRS 2012 DISEASES OF THE COLON & RECTUM VOLUME 55: 12 (2012) intersphincteric fistula tract group. The median interval from the seton placement to the definitive surgery was 14 (range, 8–74) weeks. Over a median follow-up of 13 (range, 4–67) months, 15 (62.5%) patients had successful outcomes. Hence when performed as the initial definitive procedure after a seton, the endorectal advancement flap technique had a significantly higher success rate in comparison with the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract approach (93.5% vs 62.5%) (p = 0.006). CONCLUSION : In patients who have had seton placement for high anal fistulas, the endorectal advancement flap technique is associated with better short-term outcomes in comparison with the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract technique. KEY WORDS: Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; Advancement flap; Anal fistula; Seton. F istulotomy is frequently performed for low anal fistulas with satisfactory outcomes.1,2 If this is performed in patients with high fistulas, there is a real risk of fecal incontinence.3,4 In such a situation, it is not infrequent that a seton would be inserted to ensure continual drainage of any sepsis before any subsequent definitive intervention.5,6 The advancement flap procedure for high anal fistula has remained popular over the years as a sphincter-preserving procedure while tackling the underlying pathology at the internal opening.7–9 Although this operation has been credited with success rates of about 70%,7–9 it is technically demanding and may be a difficult procedure to master. Another anal sphincter-preserving operation is the ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) technique.10–15 The simplicity of the procedure, coupled with success rates of 68% to 94%, has popularized the technique.10–15 Because the accurate identification of the intersphincteric tract holds the key to the success of the 1273 1274 technique, some authors have proposed leaving a seton in situ for a period of 8 to 12 weeks before the LIFT procedure to enable maturation of the fistula tract around the seton.12,13 However, there are currently no published data to confirm the effectiveness of the seton in such situations. This study aims to compare the outcomes between the endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) and the LIFT procedures as the definitive surgery after seton placement for high anal fistulas. MATERIALS AND METHODS A retrospective review was performed on all patients who underwent the ERAF or the LIFT procedure between April 2006 and July 2011 for high anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin following seton placement. Patients with fistulas from Crohn’s disease or HIV were excluded. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. The degree of sphincter involvement was determined by using endoanal ultrasonography (EAUS) in the office. This is performed either preoperatively or subsequent to seton insertion if the fistula was not suspected initially. It is our unit’s routine practice to perform an EAUS in all office patients with suspected anal fistula. The final classification was determined after concordance with the operative findings. A high fistula was defined as one that encompassed more than one-third of the external sphincter complex.16,17 Hence, should a high anal fistula be diagnosed intraoperatively without previous EAUS, the options included inserting a draining seton or performing a definitive procedure. This was left to the discretion of the primary surgeon. Likewise, the decision to perform an ERAF or a LIFT procedure was also determined by the surgeon. Most of the procedures were performed by the 2 senior authors (D.C.K., C.B.T.), with an equal proportion of the ERAF and LIFT procedures being performed by each surgeon. The LIFT technique adopted has been described by our group recently.13 For the ERAF procedure, following preoperative bowel preparation with the use of a sodium phosphate enema, the patient was placed in the prone jackknife or lithotomy position, depending on the location of the internal opening. The seton was removed and the fistula reassessed. Epinephrine (1:200,000) was then instilled into the submucosal area of the planned flap incision. A rhomboid-shaped flap incorporating the mucosa, submucosa and part of the internal anal sphincter was created by using sharp dissection. The base of the flap was 2 to 3 times wider than the apex to ensure adequacy of the blood supply to the distal end. The size of the flap was determined by the area of the intended defect with some overlap. The distal edge of the flap with the internal fistula opening was excised along with the cryptoglandular TAN ET AL: SURGERY FOR HIGH FISTULA AFTER SETON infective focus. The internal opening defect on the internal sphincter was curetted and closed with the use of 2/0 polyglactin suture. The mucocutaneous flap was then advanced distally to cover the defect and secured without tension with the use of 2/0 polyglactin sutures. The external opening was debrided and left open. Postoperatively, all patients were prescribed with oral analgesics, regular irrigation to the operative area by using the shower head, and a 1-week course of oral antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate or ciprofloxacin and metronidazole). Patients were also advised to refrain from activities that could place tension on the flap (excessive squatting or straining). The patients were reviewed in the office 1 to 2 weeks after surgery. Subsequent follow-up was conducted every 2 or 4 weeks until complete healing. A successful outcome was defined as the complete healing of the surgical wounds and the external opening. Failure was defined as the presence of persistent discharge through the external opening or the intersphincteric wound. All failures were diagnosed clinically and verified by EAUS. The Fisher exact test was used to determine variables that were associated with failures. All analyses were performed with the use of the SPSS 17.0 statistical package (Chicago, IL), and all p values reported were 2-sided with values of <0.05 considered statistically significant. RESULTS ERAF Group Thirty-one patients underwent the ERAF procedure following seton placement (Table 1). There was a significant male majority of 87.1% (n = 27), and the median age of this group was 49 (range, 19–74) years. There were a total of 55 previous related surgeries for this group, 18 (58.1%) patients had undergone 2 or more previous operations (Table 2). The median interval from the placement of the seton to the ERAF procedure was 13 (range, 4–284) weeks. Over a median follow-up of 6 (range, 2–26) months, 29 (93.5%) patients had successful outcomes (Table 3). In the 2 failures, 1 developed an abscess over the site of the TABLE 1. Demographics of the ERAF and LIFT groups Characteristics Male sex Median age (range), y Median interval between seton and definitive procedure (ERAF/LIFT), wk Median number of previous procedures ERAF group (n = 31) LIFT group (n = 24) p 27 (87.1%) 49 (19–74) 13 (4–284) 21 (87.5%) 41 (16–75) 14 (8–74) NS NS NS 2 (1–4) 1 (1–3) NS ERAF = endorectal advancement flap; LIFT = ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; NS = not significant (p > 0.05). 1275 DISEASES OF THE COLON & RECTUM VOLUME 55: 12 (2012) TABLE 2. Description of perianal surgeries before the insertion of the seton Characteristics Details of perianal surgeries before seton insertion Incision and drainage Fistulotomy/fistulectomy LIFT Fibrin glue ERAF group (n = 31) (%) LIFT group (n = 24) (%) 19 (61.3) 7 (22.6) 2 (6.5) 1 (3.1) 13 (54.2) 0 0 0 ERAF = endorectal advancement flap; LIFT = ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract. previous external opening 6 months after the ERAF procedure. Only a drainage procedure was required after an EAUS excluded the presence of an internal opening. The other patient had a recurrence of the fistula. He first underwent drainage of the associated abscess with placement of a seton 7 months after the ERAF procedure. A fistulotomy was then performed 4 months later. LIFT Group A total of 24 patients, with a significant male majority of 87.5% (n = 21), and a median age of 41 (range, 16–75) years, underwent the LIFT approach (Table 1). They underwent 31 related surgeries before the LIFT procedure (Table 2). Only 6 (25.0%) of them underwent 2 or more previous operations. The median interval from the placement of the seton to the LIFT procedure was 14 (range, 8–74) weeks (Table 1). After a median follow up of 13 (range, 4–67) months, only 15 (62.5%) patients had a successful outcome. The 9 patients whose procedures had failed underwent the subsequent operations as shown in Table 3. The median interval from the LIFT procedure to their subsequent surgeries was 12 (range, 2–49) weeks. It is noteworthy that 2 patients underwent a successful ERAF procedure, and 1 patient had a successful repeat LIFT procedure performed. When we compared the outcomes between the 2 groups, the ERAF group had a significantly higher success rate than the LIFT group (93.5% vs 62.5%, p = 0.006). TABLE 3. Details of subsequent interventions in patients in whom the ERAF or the LIFT procedure faileda Characteristics ERAF group (n = 31) Details of subsequent intervention, n (%) Incision and drainage 1 (3.2) Fistulotomy/fistulectomy 1 (3.2) Seton 0 ERAF 0 LIFT 0 LIFT group (n = 24) 1 (4.2) 4 (16.7) 4 (16.7) 2 (8.3) 1 (4.2) ERAF = endorectal advancement flap; LIFT = ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract. a Three patients had several subsequent procedures. None of the other variables were statistically significant (Table 4). DISCUSSION Our study demonstrated that the ERAF technique was associated with a higher success rate than the LIFT approach in patients with high anal fistulas who had a seton inserted previously. This was despite the higher proportion of patients who underwent 2 or more previous operations in the ERAF group. This finding was rather unexpected, because it has been postulated by previous reports that the seton should lead to a better outcome because it enables better identification of the intersphincteric tract by allowing maturation of the tract around the seton.12,13 The identification of the tract has always been deemed to be the key to the success of the LIFT technique. We postulate that the higher failure rate in the LIFT group could be attributed to several reasons. First, the scarring following the resolution of the acute inflammatory phase would have resulted in fibrosis and obliteration of the intersphincteric space. This would then make the dissection in the intersphincteric plane difficult. Any buttonhole breach of the internal sphincter and anal mucosa during dissection would also lead to a higher risk of failure. Moreover, the resultant scarring around the seton might have made the localization of the anal gland and its complete excision difficult. On a similar note, the scarring, especially from repeated surgeries, would have rendered the surrounding tissue ischemic, which would then lead to poor wound healing. The internal opening is also more likely to be fixed from fibrosis and adherent to the intersphincteric plane and might not close as readily had a seton not been inserted previously. If the aforementioned holds true, the higher success rate of the ERAF technique is perhaps not surprising.7–9,18–20 Apart from being able to bring healthy and well-vascularized tissues to the "scarred" surgical field, the ERAF approach would have addressed the internal opening and, more importantly, the underlying anal gland, adequately. TABLE 4. Comparison of the outcomes between groups Characteristics Median duration of follow-up, mo (range) Outcome of surgery Successful Failed and required further intervention ERAF group (n = 31) LIFT group (n = 24) 6 (2–26) 13 (4–67) 29 (93.5) 2 (6.5) 15 (62.5) 9 (37.5) p 0.006 ERAF = endorectal advancement flap; LIFT = ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract. 1276 Despite this study being retrospective in nature, this is the first time that a comparative study has been performed between the LIFT and the ERAF techniques in such a highly selected group of patients. Although the number of patients in each group is small, our findings may guide the subsequent management in patients with high anal fistulas with a seton placed previously. Our study would suggest that the ERAF is a better option in the approach to fistulas after seton placement. The technical challenges in mastering the ERAF technique are nevertheless still worth considering. There have also been reports citing incontinence rates of up to 35% of patients after the ERAF procedure.21,22 Deterioration in the anal manometric measurements has also been reported.21,22 This finding has been attributed to the usage of anal retractors causing stretch injury and the part of the internal sphincter that is incorporated in the flap. Although there were no patients who reported any incontinent symptoms, the absence of any functional data is a significant limitation of this study. Given the technical challenges in the ERAF technique and reports of incontinence, we believe that there is still a role for the LIFT procedure in patients with high anal fistulas after seton placement. The attractiveness of the LIFT procedure has always been its technical simplicity and the avoidance of any expensive implants.10,11 Although the presence of the seton has been purported to be useful in delineating the exact location of the intersphincteric tract, bolstering the confidence of the surgeons, we have not seen a commensurate increase in the success rates of the LIFT procedure. Nevertheless, failures following the LIFT procedure are usually easily managed.13 The resultant downstaging of the severity of the fistula leads to a smaller and easier procedure, such as local treatment, drainage of the abscess, or fistulotomy.13 We recognize several limitations in our study. The determination of the outcome of the surgery by the single surgeon leads to a considerable observer bias. The choice of the surgical technique by the primary surgeon may also result in a selection bias. The duration of the follow-up is also not comparable, being shorter in the ERAF group. Given that the 2 recurrences in the ERAF group occurred 6 and 7 months after their operations, the shorter follow-up durations reported in the ERAF group may have masked further failures. Although our study continues to shed more light about the LIFT procedure, further work is still warranted to confirm the long-term outcome of this relatively new technique. In addition, the determination of any predictors of failure of this new technique and its role in low transsphincteric fistulas would be useful in defining its role in the surgical management of all anal fistulas. CONCLUSIONS In patients who have had seton placement for high anal fistulas, the ERAF approach is associated with better outcomes TAN ET AL: SURGERY FOR HIGH FISTULA AFTER SETON in comparison with the LIFT technique. However, given the simplicity of the technique, we would still perform the LIFT procedure in patients presenting for the first time after seton drainage. However, in patients with multiple previous surgeries and a scarred battlefield perianal region, we will recommend an ERAF where expertise is available. REFERENCES 1. Abbas MA, Jackson CH, Haigh PI. Predictors of outcome for anal fistula surgery. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1011–1016. 2. Malik AI, Nelson RL. Surgical management of anal fistulae: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:420–430. 3. García-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong DW, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD. Cutting seton versus two-stage seton fistulotomy in the surgical management of high anal fistula. Br J Surg. 1998;85:243–245. 4. Hämäläinen KP, Sainio AP. Cutting seton for anal fistulas: high risk of minor control defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1443–1447. 5. Williams JG, MacLeod CA, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM. Seton treatment of high anal fistulas. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1159–1161. 6. Van Tets WF, Kuijpers JH. Seton treatment of perianal fistula with high anal or rectal opening. Br J Surg. 1995;82:895–897. 7. Jarrar A, Church J. Advancement flap repair: a good option for complex anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1537–1541. 8. Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, et al. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1616–1621. 9. Christoforidis D, Pieh MC, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:18–22. 10. Rojanasakul A. LIFT procedure: a simplified technique for fistula-in-ano. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:237–240. 11. Rojanasakul A, Pattanaarun J, Sahakitrungruang C, Tantiphlachiva K. Total anal sphincter saving technique for fistula-inano; the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:581–586. 12. Shanwani A, Nor AM, Amri N. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT): a sphincter-saving technique for fistula-inano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:39–42. 13. Tan KK, Tan IJ, Lim FS, Koh DC, Tsang CB. The anatomy of failures following the ligation of intersphincteric tract technique for anal fistula: a review of 93 patients over 4 years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1368–1372. 14. Aboulian A, Kaji AH, Kumar RR. Early result of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:289–292. 15. Bleier JI, Moloo H, Goldberg SM. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract: an effective new technique for complex fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:43–46. 16. van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Fibrin glue and transanal rectal advancement flap for high transsphincteric perianal fistulas; is there any advantage? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:697–701. 17. van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Bakx R, Reitsma JB, Slors JF. Long-term functional outcome and risk factors for recurrence DISEASES OF THE COLON & RECTUM VOLUME 55: 12 (2012) after surgical treatment for low and high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1475–1481. 18. Golub RW, Wise WE Jr, Kerner BA, Khanduja KS, Aguilar PS. Endorectal mucosal advancement flap: the preferred method for complex cryptoglandular fistula-in-ano. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:487–491. 19. Dubsky PC, Stift A, Friedl J, Teleky B, Herbst F. Endorectal advancement flaps in the treatment of high anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin: full-thickness vs. mucosal-rectum flaps. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:852–857. 1277 20. Dixon M, Root J, Grant S, Stamos MJ. Endorectal flap advancement repair is an effective treatment for selected patients with anorectal fistulas. Am Surg. 2004;70:925–927. 21. Uribe N, Millán M, Minguez M, et al. Clinical and manometric results of endorectal advancement flaps for complex anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:259–264. 22. Perez F, Arroyo A, Serrano P, et al. Randomized clinical and manometric study of advancement flap versus fistulotomy with sphincter reconstruction in the management of complex fistula-in-ano. Am J Surg. 2006;192:34–40.