Use of Phillips`s five level training evaluation

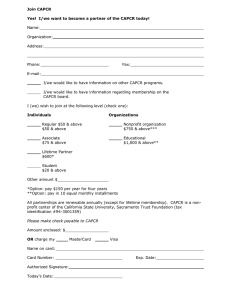

advertisement