Chapter 1 – Introduction to the Research Problem

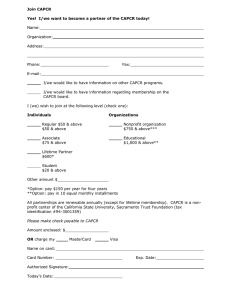

advertisement