ASIC submission to Review of small amount credit contract laws

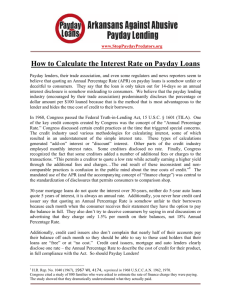

advertisement