Conclusion Results Methods Discussion Introduction

advertisement

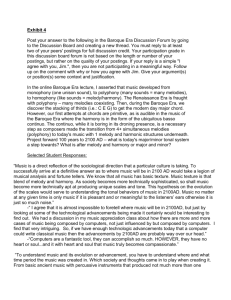

MUSIC PERCEPTION: AN FMRI STUDY OF THE MERE EXPOSURE EFFECT Anders C. Green , Peter Vuust , Tue B. Hartmann , Hans Stødkilde-Jørgensen , 3 1,2 Andreas Roepstorff , Klaus B. Bærentsen 1,2 3,4 1 2 Department of Psychology, University of Aarhus, Denmark, 2MR Research Centre, Aarhus University Hospital, 3Center for Functionally Integrative Neuroscience, Aarhus University Hospital, 4Royal Academy of Music, Aarhus. 1 Introduction Whether we like a piece of music is not solely decided by the actual music itself, but also by how well we as listeners understand it: We tend to like what we know. What we know is greatly influenced by how often we have heard the given piece of music. This is the so-called mere exposure effect1, which has also been shown specifically for music2. However, the neural underpinnings of the phenomenon are not well understood. Some preliminary insights from an ongoing study are presented here. Methods Experimental Design The experiment consists of three main parts: A. Learning phase: Before entering the scanner, the subjects are accustomed to some of the melodies in varying degrees. Details: 18 different melodies from three groups of six, with presentation frequencies of 2, 8, and 32 times, respectively, are presented in pseudo-randomised order. Subject focus is maintained by having them identify the occurence of notes detuned by 50 cents, contained in a separate group of melodies inserted into the stimulus order. B. Rating phase in scanner: In the scanner, subjects listen to each melody again once, along with a group of new melodies. During the scan, the subjects rate by a button press how much they like each melody. Details: The 18 melodies from the learning phase are played again once each, together with 6 new ones. Jittered ISI of 2-8 secs with silence. The subject task is to rate their liking of each melody immediately after its completion (1-5 scale button press). Eyes open, visual fixation. Results Liking Recognition C. Recognition test phase: Subsequently, subjects hear each of all the preceding melodies once again, along with yet another group of new melodies. This time, they rate their certainty of having heard a given melody before. Details: The 24 melodies from the scan phase are repeated again once each, as well as 6 new ones – creating a total of five different groups. The subject task is to rate the certainty of having heard each melody before (1-5 scale button press). Stimuli 30 specially composed, equivalent piano melodies of 15 seconds duration, presented over headphones. Melodies are in three different musical keys, and in both major and minor modes – all evenly balanced. A baseline rating of each melody was obtained from a separate group of 50 subjects. The melodies are split into five groups of six melodies each, such that the mean group baseline ratings are equal: Mean of 2.96 +/- 0.02 on a 1-5 scale. Subjects Six non-professional, but musically interested and qualified, right-handed adults: three male, three female, aged 24-32. Scanning and Data Analysis GE 1.5T MR scanner, EPI, TR 2700 msec., TE 40 msec. 34 axial slices of 5mm (no gap), covering the entire brain. DataanalysisinSPM23:Preprocessing(realignmentandunwarping,normalisation, smoothing 8mm FWHM). Parametric design, fixed effects group model. Behavioural Data fMRI Data Melodies heard the most often are rated the highest, creating a linear relationship between presentation frequency and liking, apart from the fact that the F0 and F2 groups do not differ. ANOVA testing shows the increase in liking from both F0 and F2 to F32 to be significant at p<0.05, whereas the difference either side of the F8 melodies is only approaching significance. Error bars represent SE. Areas with activity increase when melody familiarity and liking grows: Illustration of the positive relationship between recognition and liking for 2, 8, and 32 repetitions. Bilateral BA9 and BA46 Right BA10 Bilateral activations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, BA9 and BA46, in the middle frontal gyrus. A further activation site, also in the prefrontal cortex, is seen more ventrolaterally in right BA10. The expected positive effect of exposure on recognition is apparent, showing that the subjects do in fact learn the different groups of melodies, to an extent controlled by the presentation frequency. The group named F1 is the group of melodies heard for the first time during the previous scan phase. Error bars represent SE. Results from parametric contrast based on the presentation frequency of the melodies: Brain areas showing increased activity with increased number of presentations, and at the same time corresponding to increase in liking (see behavioural results). Fixed effects group result, significance at p<0.001 uncorrected, extent threshold 10 voxels. The reverse parametric contrast yielded no significant voxels. Discussion The resulting activations show that the better known a melody is, and hence the more likeable it is, bilateral BA9 and 46 in DLPFC, and right BA10, become increasingly active. These areas are usually involved in memory retrieval, working memory and executive function – including evaluating the content of memories. Lateral parts of the frontal cortex are the more sensory inputoriented. BA9 has more specifically been associated with response selection based on evaluative processes. The involvement of the right, as opposed to left, frontopolar area BA10 is seen more often in retrieval than encoding, which makes sense in this context. Recently, a study has found the right BA10 and BA46 to be involved in decision making and evaluation in a visual task4. Regarding correspondence with earlier music-specific findings, dorsolateral and inferior frontal areas are in general found to be particularly important for music memory, together with auditory areas, and in interaction with posterior temporal regions5. A PET study of episodic music memory also finds bilateral BA 9 and 10 activation, and again strongest on the right (as well as BA7, not found in the present study)6. The finding of BA9, (right) BA10, and BA46 makes sense on this background: The better known a melody is, the more material the active memory process has to work on, and hence the greater activation in areas serving this function. Furthermore, the specific areas found are not only engaged in memory, but rather also have an evaluative function. It is worth noticing, though, that none of the limbic system areas also associated with emotional responses are found differentially active here, as melodies gets more well known and better liked. This might point to the fact, that the ratings done by the subjects were References: more cognitive than emotional in character – perhaps due to the slightly artificial nature of the stimuli used. Notice also the absence of auditoryspecific activations in the group result, though some individuals showed activation of auditory association areas. On a more general note, the importance of recognition and expectancy for liking has often been stressed within music research. There is some evidence, though, that the effect of recognition on liking might not be linear, but curvilinear, following an inverted-U curve2. That is, a piece of music can become too familiar to the listener, and consequently seem boring and less likeable. On this ground it is somewhat surprising that the present study does not show this satiation effect, given the relatively large maximum number of presentations (32). Post-experiment interviews with the subjects underscore this fact, in that they all mention recognisability and predictability as reasons for rating a melody positively. Conclusion The mere exposure effect was replicated fairly well for the melodic stimuli used, resulting in an overall linear effect of exposure on liking. This positive effect on liking was accompanied by an increase in brain activity in dorsolateral prefrontal regions involved in memory retrieval and evaluative executive functions. 1. Zajonc, R. (1968). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1-28. 2. Szpunar, K. K. et al. (2004). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(2), 370-381. 3. http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ 4. Fleck, M. S. et al. (2006, in press). Cerebral Cortex. 5. Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R. J. (2005). Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 89-114. 6. Platel, H. et al. (2003). NeuroImage, 20, 244-256.