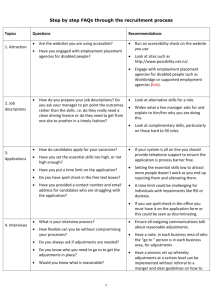

Guidance on making reasonable adjustments for students and staff

advertisement