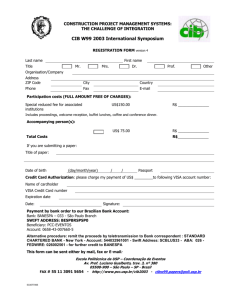

São Paulo, Brazil

advertisement