The margin of appreciation - European Court of Human Rights

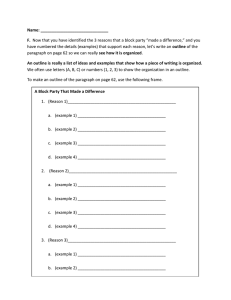

advertisement