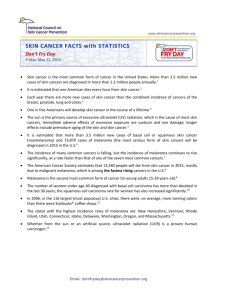

Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers

advertisement