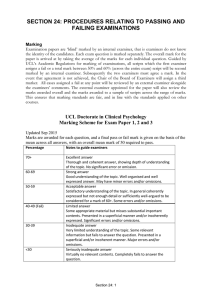

Research into alternative marking review processes for

advertisement