The Laws, Regulations, Guidelines, and Industry Practices

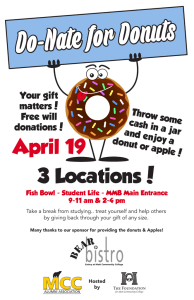

advertisement