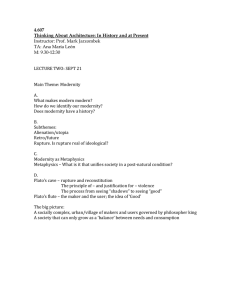

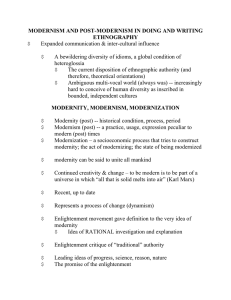

Theorizing Modernity and Technology

advertisement