Final Exam Solutions

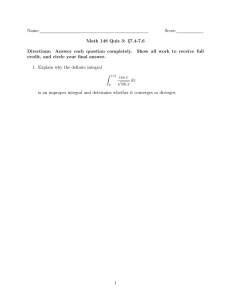

advertisement

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

1

Spring, 2009

(5 points) Indicate whether the following statements are True or False by circling the appropriate

letter. No justifications are required.

T F The (vector) projection of h3, 17, −19i onto h1, 2, 3i is equal to the (vector) projection

of h3, 17, −19i onto h−5, −10, −15i.

Solution: This is True, since h−5, −10, −15i = −5h1, 2, 3i.

T F The angle between the vectors h1, −3, 7i and h−4, 6, 1i is obtuse (greater than π2 ).

Solution: This is True. We calculate the cosine of the angle θ between u = h1, −3, 7i and

v = h−4, 6, 1i by

cos(θ) =

u·v

(1)(−4) + (−3)(6) + (7)(1)

−15

=

=

< 0.

|u| |v|

|u| |v|

|u| |v|

Since cos(θ) < 0, the angle θ must be obtuse.

T F If F = hP, QiZis a vector field with the property that Qx −Py = 0, then Green’s Theorem

F · dr = 0 for any curve C.

implies that

C

Solution: This is False. Green’s Theorem implies that this integral is zero for any closed

path C, but not for any path at all.

T F The tangent plane to x2 − y 2 + 4z 2 = 1 at the point (1, 2, 1) is x − 2y + 4z = 1.

Solution: This is True. The normal to the level surface g(x, y, z) = x2 − y 2 + 4z 2 = 1 at the

point (1, 2, 1) is ∇g(1, 2, 1). Since ∇g = h2x, −2y, 8zi, the normal is n = ∇g(1, 2, 1) = h2, −4, 8i.

The tangent plane is therefore

h2, −4, 8i · hx − 1, y − 2, z − 1i = 0

or

2x − 4y + 8z = 2

or

x − 2y + 4z = 1.

This is the equation given.

T F The two curves C1 , parameterized by r1 (t) = ht2 , ti, and C2 , parameterized by

r2 (t) = h4t2 , ti, both pass through the point (0, 0). At this point, the curvature of

C1 is greater than the curvature of C2 .

Solution: This is False. Here is a graph showing these two parameterized curves:

y ..............

....

...

..

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

.

.................................................................................................................................................................................................

....

..

....

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

....

..

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

..

... C , −1 ≤ t ≤ 1

........ 1

.

.

.

.

.

.

......

.....

.

.

.

.

.

.....

........... C2 , − 12 ≤ t ≤ 12

...... ......................

.

............

.......

....

..........

x

... ..........

1

.

.

.... ............

...............

.....

....

.....

......

.......

........

........

.....

−1

1

Intuitively, the curve C2 is curving more at the origin, so has a greater curvature. Here’s a

rigorous way of thinking of this. The osculating circle for C1 at the origin is much larger than

the same circle for C2 . But the radius for the osculating circle is the inverse of the curvature

κ, so this is saying that κ11 > κ12 . Thus κ1 < κ2 . Put another way, the curvature for C1 is less

than that of C2 , not greater than.

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

2

Spring, 2009

(4 points) Match the sketch of each quadric surface with the appropriate equation. You do not

need to justify your choices.

(a) x2 + 2y 2 + z 2 = 1

(b) x2 + 2y 2 − z 2 = 1

(c) x2 − 2y 2 − z 2 = 1

(d) x2 + 2y 2 − z 2 = 0

I.

II.

III.

IV.

Solution:

One way to do this is to look at traces. Here’s a little table of traces for our four

equations, together with the corresponding sketch:

Equation

x = k trace

y = k trace

z = k trace

Quadric

(a) x2 + 2y 2 + z 2 = 1

ellipses (|x| ≤ 1)

ellipses (|y| ≤ 21 )

ellipses (|z| ≤ 1)

IV

(b) x2 + 2y 2 − z 2 = 1

hyperbolas (all x)

hyperbolas (all y)

ellipses (all z)

II

(c) x2 − 2y 2 − z 2 = 1

ellipses (all |x| > 1)

hyperbolas (all y)

hyperbolas (all z)

I

(d) x2 + 2y 2 − z 2 = 0

hyperbolas (all x)

hyperbolas (all y)

ellipses (all z > 0)

III

The difference between II and III comes in the trace at z = 0 in equation (d). There the ellipse turns

into only a point. Another

√ difference is in the x = 0 trace. For (b) this is a hyperbola but in (d) it

produces two lines z = ± 2 y (a “degenerate” hyperbola).

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

3

(6 points)

Spring, 2009

Compute the integral

Z

1

2Z

√

2−x

2−x

1

dy dx.

2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4

Hint: Change the order of integration.

Solution:

Here’s a picture of the region D over which we are integrating. Notice that√the y

coordinates are bounded below by the line y = 2 − x and above by the hyperbola y = 2 − x

between x = 1 and x = 2.

y ..............

...

.....

...

.....

..

.....

...

.....

.....

...

.....

...

.....

.

.....

.

.....

.......... ...

............

.....

.

.....

.

.

.

. .....

.....

.... ..................

.....

.........

...

.....

.........

.....

...

.........

..

........

...

........ .........

........ .....

...

........ ....

...

.............

...

...

...

..

....

...

.... .

...

......

...

........

........

...

..........

...

..........

...

..........

.......... .

...

............

...

............

...

............

..........

...

..........

...

..........

...

........

.......

...

......

...

....

...

...

..

...

.

.

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..

. ....

...

... ........

.....

...

...

.....

..

...

.

.....

..

.....

...

.....

...

.

...

.

.....

..

.

.....

...

.

.

.

.

.

.

...

..

..

..........

.............

..... ........

..... ........

..... ......

..... .....

..... ....

..... ...

..... ...

........

..

1

1

x

2

That is, we can write R as

R = {(x, y) : 2 − x ≤ y ≤

√

2 − x, 1 ≤ x ≤ 2}.

To change the order of integration, we write x in terms of y for both curves. The line is simply

x = y − 2 and the parabola is x = 2 − y 2 . That is, the region R can also be written as

R = {(x, y) : y − 2 ≤ x ≤ 2 − y 2 , 0 ≤ y ≤ 1}.

Thus we can re-write the integral as

Z 1 Z 2−y2

Z 2 Z √2−x

1

1

dy

dx

=

dx dy.

3

2

3

2y − 3y + 4

2y − 3y 2 + 4

2−x

0

2−y

1

Now we integrate:

Z

1

=

0

Z

=

0

1

x

2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4

2−y 2

dy

2−y

(2 − y 2 ) − (2 − y)

dy =

2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4

Z

0

1

y − y2

dy.

2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4

Now the substitution u = 2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4 produces du = 6(y 2 − y) dy, so we can continue

Z

y=1

−

=

y=0

=

11

1

du = − ln 2y 3 − 3y 2 + 4

6u

6

1

(ln(4) − ln(3)) .

6

1

0

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

4

(7 points)

Spring, 2009

Find the volume of the solid enclosed by the cylinders x2 + z 2 = 1 and y 2 + z 2 = 1.

z

z

y

y

x

x

Solution:

There are

Z Z Zmany ways to set up the integral. Let’s do it as a triple integral, so if E is the

1 dV . We can describe our solid as E = {(x, y, z) : x2 +z 2 ≤ 1, y 2 +z 2 ≤ 1}.

solid, then we want

E

It’s hard to write bounds for z in terms of x and y: we know that z 2 ≤ 1 − x2 and z 2 ≤ 1 − y 2 , so

we would have to write something like z 2 ≤ the smaller of 1 − x2 and 1 − y 2 , which would be a big

mess. We can get around this problem by making the z integral the outer integral. Then we just

have to say that z goes from −1 to 1.

√

√

Since x2 ≤ 1 − z 2 and y 2 ≤ 1 − z 2 , so x and√y both go from − 1 − z 2 to 1 − z 2 . (That is, the

z =constant trace is a square of side length 2 1 − z 2 .) This gives an iterated integral

Z 1 Z √1−z 2 p

Z 1 Z √1−z 2 Z √1−z 2

1 dx dy dz =

2 1 − z 2 dy dz

√

√

√

−1

− 1−z 2

− 1−z 2

− 1−z 2

−1

Z

1

=

4(1 − z 2 ) dz

−1

4z 3

= 4z −

3

=

z=1

z=−1

16

3

Another approach is to split the region up into equally-sized pieces and find the volume of a single,

representative piece. We’ll cut the region by two planes, y = x and y = −x. The advantage here is

that the height (the bounds for z) in each region depend on only x (or on only y). Here’s the region

projected onto the xy-plane:

y

.....

.....

.....

.....

.........

.....

.....

.....

.....

...

.....

.....

.

.

.

.

.

.

.....

...

..

....

.....

.

..

...

...

....

...

.......

......

.

.

.

....

........

..............

....

..........

............

...

............

..............

..............

...

........

........................

.

..........................

...

.................... .. .............................

........... . ...........

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................

..................... .. .....................

................... .. ...................

.................

.................

....

...............

........

.............

....................

...

...........

...........

...

.........

.........

.

.

.......

....

..

.....

........

.

...

...

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.....

.

...

.

.

.

.

.....

.

.

.

...

.

.....

.

.

.

.

.

.....

.

...

.

.

.

.

.....

.

.

.

....

.

.....

.

.

.

.

..

....

...

...........................................................................

.. ......

.. ..

.... .....

.. ......

.

.

..... .....

...

..

.......

...

..

.

..

.. .......

..

.

.

..... .....

.. .....

... .

.. ....

..........................................................................

y=x

x

y = −x

√

√

On the shaded region

z variespbetween − 1 − x2 and 1 − x2 , while on the unshaded regions z

p

varies between − 1 − y 2 and 1 − y 2 . We’ll integrate over the region R (this is one-quarter of the

volume of the full region). Thus the full volume of the region is

Z Z Z √1−x2

Z 1 Z x Z √1−x2

16

Volume = 4

1 dz dA = 4

1 dz dy dx = .

√

√

3

2

2

− 1−x

0

−x − 1−x

R

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

5

(8 points)

Spring, 2009

Suppose the gradient vector of a function f (x, y, z) at the point (3, 4, −5) is h1, −2, 2i.

(a) (2 points) Find the values of the partial derivatives fx , fy , and fz at the point (3, 4, −5).

Solution: Since the gradient vector of a function f (x, y, z) is the vector ∇f = hfx , fy , fz i,

we have that fx = 1, fy = −2, and fz = 2 at the point (3, 4, −5).

(b) (3 points) Find the maximum directional derivative of f at the point (3, 4, −5) and the unit

vector in the direction in which this maximum occurs.

Solution: Recall that the directional derivative Du f = ∇f · u is greatest in the direction

h1,−2,2i

∇f

of ∇f . Thus the directional derivative is greatest when u = |∇f

= h 31 , − 23 , 23 i. The

3

| =

directional derivative in the direction of u is thus Du f = ∇f · u = h1, −2, 2i · h1,−2,2i

= 3. (This

3

is, of course, simply |∇f |.)

(c) (3 points) If f (3, 4, −5) = −2, estimate f (3.1, 4.1, −4.8) using linear approximation.

Solution:

Recall that the linearization L(x, y, z) near (x, y, z) = (a, b, c) of the function

f (x, y, z) is

L(x, y, z) = f (a, b, c) + ∇f (a, b, c) · hx − a, y − b, z − ci

or, equivalently,

L(x, y, z) = f (a, b, c) + fx (a, b, c)(x − a) + fy (a, b, c)(y − b) + fz (a, b, c)(z − c).

Here (a, b, c) = (3, 4, −5), ∇f (3, 4, −5) = h1, −2, 2i, and f (3, 4, −5) = −2. Thus

L(x, y, z) = −2 + h1, −2, 2i · hx − 3, y − 4, z + 5i

The linear approximation of f (x, y, z) for (x, y, z) near (3, 4, −5) is simply f (x, y, z) ≈ L(x, y, z).

Thus we get

f (3.1, 4.1, −4.8) ≈ L(3.1, 4.1, −4.8) = −2 + h1, −2, 2i · h3.1 − 3, 4.1 − 4, −4.8 + 5i

= −2 + h1, −2, 2i · h0.1, 0.1, 0.2i

− 2 + 0.1 − 0.2 + 0.4 = −1.7.

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

6

Spring, 2009

(8 points) Let S be the part of the elliptic cylinder 4x2 + 9z 2 = 36 lying between the planes y = −3

and y = 3 and below the plane z = 0. Here are two views of this cylinder, from different perspectives:

z

z

y

y

x

x

(a) (4 points)

Write an iterated integral which gives the surface area of S. You need not

evaluate the integral, but your integral should be simplified enough so that all that is required

is integration (that is, the integrand contains no dot or cross products or even vectors).

Solution: Recall that the scalar surface area element dS is |ru × rv | du dv, where r(u, v) is

a parameterization of the surface S. So all we need is a parameterization.

There are several ways to parameterizeDthis. Perhaps the most

direct is as a q

graph z = f (x, y).

E

√

2

We solve for z and find that r(x, y) = x, y, − 13 36 − 4x2 has |rx × ry | = 9+3x

, so

9−x2

r

Z 3Z 3

9 + 3x2

dy dx.

Surface Area =

9 − x2

−3 −3

Note the negative sign in the expression for z and also the general unpleasantness of computing

with this expression.

A nicer expression involves parameterizing the elliptical cylinder using sines and cosines:

r(y, θ) = h3 cos(θ), y, 2 sin(θ)i (with −3 ≤ y ≤ 3 and π ≤ θ ≤ 2π). From this we get

i

j

k

0

1

0

ry × rθ =

= h2 cos(θ), 0, 3 sin(θ)i ,

−3 sin(θ) 0 2 cos(θ)

p

and so |ry × rθ | = 9 sin2 (θ) + 4 cos2 (θ). Thus

Z 2π Z 3 q

Surface Area =

9 sin2 (θ) + 4 cos2 (θ) dy dθ.

π

−3

(b) (4 points) Let F(x, y, z) = hx, ey , zi. Evaluate the flux integral

ZZ

F · dS if S is oriented with

S

normal vectors pointing upward (that is, so the normal vectors have positive z component).

Solution:

We use the second parameterization from part (a), namely r(y, θ) =

h3 cos(θ), y, 2 sin(θ)i, π ≤ θ ≤ 2π, −3 ≤ y ≤ 3. From the calculation above, ry × rθ gives

us the wrong orientation (recall that π ≤ θ ≤ 2π, so sin(θ) ≤ 0), so we use rθ × ry =

h−2 cos(θ), 0, −3 sin(θ)i instead. Thus

ZZ

ZZ

F · dS =

F(r(y, θ)) · (rθ × ry ) dA

S

Z

R

2π

Z

3

h3 cos(θ), ey , 2 sin(θ)i · h−2 cos(θ), 0, −3 sin(θ)i dy dθ

=

π

Z

2π

−3

Z

3

−6 dy dθ = −36π.

=

π

−3

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

7

Spring, 2009

(14 points) Let C be the curve of intersection of the cylinder x2 +y 2 = 4 and the plane 3x+2y+z = 6.

(a) (2 points) Parameterize C. Be sure to give bounds for your parameter.

Solution:

This intersection is an ellipse. It is simplest to parameterize by noticing that

its projection into the xy-plane is simply the circle x2 + y 2 = 4. This is parameterized

by x = 2 cos(t) and y = 2 sin(t); the z-coordinate on the ellipse can be found by solving

for z in the plane: z = 6 − 3x − 2y. Thus we end up with the parameterization r(t) =

h2 cos(t), 2 sin(t), 6 − 6 cos(t) − 4 sin(t)i with 0 ≤ t < 2π.

(b) (3 points) Write an integral that gives the arc length of C. You need not evaluate your

integral, but your integral should be simplified enough so that all that is required is integration

(that is, the integrand contains no dot or cross products or even vectors).

Solution: Recall that the incremental arc length element is ds = |r0 (t)| dt. (If we envision

r(t) as describing the path of a particle, then |r0 (t)| is the speed of this particle while ds

dt is the

rate of change of the distance this particle has traveled. These must agree.) This is simply

Z 2π

Arc Length =

− 2 sin(t), 2 cos(t), 6 sin(t) − 4 cos(t) dt

0

Z

2π

q

4 sin2 (t) + 4 cos2 (t) + 36 sin2 (t) − 24 sin(t) cos(t) + 16 cos2 (t) dt

2π

q

40 sin2 (t) − 24 sin(t) cos(t) + 20 cos2 (t) dt

2π

q

2 10 sin2 (t) − 6 sin(t) cos(t) + 5 cos2 (t) dt.

=

0

Z

=

0

Z

=

0

(c) (4 points) A bee is flying along the curve C in a room where the temperature is given by

f (x, y, z) = 5x + 5y + 2z. What is the hottest point the bee will reach?

Solution: Maximize f (r(t)) = 10 cos t + 10 sin t + 12 − 12 cos t − 8 sin t = 12 − 2 cos t + 2 sin t.

The derivative of this is 2 sin t + 2 cos t, which is 0 when sin t = − cos t = ± √12 . So, the

√ √

√ √ √

√

√

hottest point is − 2, 2, 6 + 2 where f (− 2, 2, 6 + 2) = 12 + 2 2. (The other point,

√

√

√ √

√

√

√

2, − 2, 6 − 2 where f ( 2, − 2, 6 − 2) = 12 − 2 2.

Alternatively, use Lagrange multipliers to maximize 5x + 5y + 2z subject to the constraints

x2 + y 2 = 4 and 3x + 2y + z = 6. This gives h5,√5, 2i = λh2x, 2y, 0i + µh3, 2, 1i, so µ = 2, and

h−1, 1, 0i = λh2x, 2y, 0i. Therefore, y = −x = ± 2, as before.

Z

D

E

3

(d) (5 points) Let F(x, y, z) = x2 y, ey − xy 2 , cos z 2 . Evaluate the line integral

F · dr if C is

C

oriented counterclockwise when viewed from above.

Solution:

Use Stokes’ Theorem: let S be the part of the plane 3x + 2y + z = 6

inside the cylinder x2 + y 2 = 4, oriented with upward normals. Parameterize this by

r(x, y) = hx, y, 6 − 3x − 2yi, where the points (x, y) lie in R, the disk x2 + y 2 ≤ 4. Then

rx × ry = h3, 2, 1i (which is the correct orientation for Stokes’), and curl F = h0, 0, −x2 − y 2 i.

Hence

ZZ

ZZ

curl F · dS =

curl F(r(x, y)) · (rx × ry ) dA

S

R

ZZ

=

Z

R

2π

h0, 0, −x2 − y 2 i · h3, 2, 1i dA =

−(x2 + y 2 ) dA

R

Z

=

0

ZZ

0

2

−r2 · r dr dθ = −8π

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

8

(6 points)

Spring, 2009

y ................

..

...

Evaluate the line integral

Z

(x4 + 3y) dx + (5x − y 3 ) dy,

C

where C is the boundary of the square with vertices (4, 0), (0, 4), (−4, 0),

and (0, −4), traversed counterclockwise.

..

4 ..............................

.

.

.

.

.. . . .........

C2 ..................................................................................................... C1

.........................................

.....................................

..................................................................

..

.

................

.

..............................................D

.

.

. . . . . . . ...

.

.

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............

...

.

......................................................................................................

x

−4 ...................................................................................................................................................... 4

................................................................

C3 .................................................................... . C4

.........

−4 ........

...

..

R

Solution: The simplest way to do this is to use Green’s Theorem, which says that C P dx+Q dy =

RR

D (Qx − Py ) dA, where C is the oriented boundary of the region D. In our case, this means D is

the solid square (as shaded, above), P = x4 + 3y, Q = 5x − y 3 , and so Qx − Py = 2. Thus

ZZ

Z

2 dA = 2 Area(D).

(x4 + 3y) dx + (5x − y 3 ) dy =

D

C

√

Since D is a square with side length 4 2, the area of D is 32 and so the line integral is 64.

Another approach is to just compute the line integral directly. I’ve added labels to the picture

(above), so the four line segments are now labeled as C1 through C4 . We’ll do the line integrals

along each curve more or less without comment, starting with a parameterization and proceeding to

the line integral.

Along C1 : Use hx, yi = h4 − t, ti (with 0 ≤ t ≤ 4), so hdx, dyi = h−dt, dti and

Z

4

Z

3

(x + 3y) dx + (5x − y ) dy =

C1

4

1264

(4 − t)4 + 3t (−dt) + 5(4 − t) − t3 dt = −

= −252.8.

5

0

Along C2 : Use hx, yi = h−t, 4 − ti (with 0 ≤ t ≤ 4), so hdx, dyi = h−dt, −dti and

Z

(x4 +3y) dx+(5x−y 3 ) dy =

4

Z

C2

0

624

(−t)4 + 3(4 − t) (−dt)+ 5(−t) − (4 − t)3 (−dt) = −

= −124.8.

5

Along C3 : Use hx, yi = ht − 4, −ti (with 0 ≤ t ≤ 4), so hdx, dyi = hdt, −dti and

Z

4

Z

3

(x + 3y) dx + (5x − y ) dy =

C3

4

0

784

= 156.8.

(t − 4)4 + 3(−t) dt + 5(t − 4) − (−t)3 (−dt) =

5

Along C4 : Use hx, yi = ht, t − 4i (with 0 ≤ t ≤ 4), so hdx, dyi = hdt, dti and

Z

4

3

Z

(x + 3y) dx + (5x − y ) dy =

C4

0

4

1424

t4 + 3(t − 4) dt + 5t − (t − 4)3 dt =

= 284.8.

5

The total line integral around C is the sum of these four line integrals. That is,

Z

1264 624 784 1424

320

(x4 + 3y) dx + (5x − y 3 ) dy = −

−

+

+

5=

= 64,

5

5

5

5

C

as before.

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

9

Spring, 2009

(11 points)

(a) (5 points) Find all critical points of f (x, y) = x2 + y 2 + x2 y + 4, and classify each critical point

as a local minimum, local maximum, or saddle point.

Solution:

A critical point of f (x, y) is a point where ∇f = hfx , fy i = h0, 0i. Here

∇f = h2x + 2xy, 2y + x2 i, so we have 2x(y + 1) = 0 and 2y + x2 = 0. From the first equation,

√

either x = 0 (and so y = 0 from the second equation) or

√ y = −1 (which means x = ± 2).

Thus we have three critical points: (x, y) = (0, 0) and (± 2, −1).

To classify these critical points, we use the second derivative test. Using fxx = 2y + 2,

2 = 4(y + 1) − 4x2 . Thus we have

fxy = fyx = 2x, and fyy = 2, we get D = fxx fyy − fxy

the following classifications:

√

√

Critical Point (− 2, −1)

(0, 0)

( 2, −1)

D

−8

4

−8

fxx

0

2

0

Saddle

Local Min

Saddle

Classification

Z

(b) (3 points)

F · dr, where C be the straight line path from (1, 1)

Evaluate the line integral

C

to (2, 2) and F(x, y) is the gradient vector field of f (x, y) (from part (a)).

Solution: We could parameterize the curve C and compute the integral directly (and we do

so below). It is simpler, however, to use the fundamental theorem of line integrals:

Z

Z

F · dr =

∇f · dr = f ( end pt ) − f ( start pt ) = f (2, 2) − f (1, 1) = 20 − 7 = 13.

C

C

The straightforward-seeming approach is much more complicated. We cab parameterize this

path by r(t) = ht, ti (with 1 ≤ t ≤ 2). Using this parameterization, our line integral is

Z

Z 2

F · dr =

F(r(t)) · r0 (t) dt

C

1

Z

2

2t + 2t2 , 2t + t2 · h1, 1i dt

=

1

Z

=

2

(4t + 3t2 ) dt = 13.

1

(c) (3 points) Here is the gradient vector field G(x, y) of another function g(x, y). (Dots represent

zero vectors.) Find all critical points of g(x, y) in the region shown, and classify each critical

point as a local minimum, local maximum, or saddle point.

Solution: Recall that a critical point of f (x, y) is where

∇f = hfx , fy i = h0, 0i. Thus a critical point is where the

vector appears as a dot, so in this region the critical points

are at (x, y) = (1, 1) and (2, 2).

We classify these points using the meaning of the gradient.

Recall that the gradient points in the direction in which f

increases fastest. The point (2, 2) is a minimum because f

increases when we move away this point in any direction.

The point (1, 1) is a saddle point because f either increases

or decreases as we move away from the point, depending on

the direction.

y

3

2

1

1

2

3

x

Math 21a

Final Exam Solutions

Spring, 2009

10 (10 points) The four points (1, 0, 0), (0, 0, 1), (0, 1, 1), and (1, 2, 0)

are all co-planar and form the vertices of a quadrilateral S. Let C be

the boundary of S directed as shown to the right, and let F = yk.

z

H0, 0, 1L

H0, 1, 1L

(a) (4 points) Find the equation of the plane that contains

the quadrilateral S.

Solution:

The plane contains the point (0, 0, 1)

and is parallel to the vectors h1 − 0, 0 − 0, 0 − 1i and

h0 − 0, 1 − 0, 1 − 1i. Thus the normal is

n = h1, 0, −1i × h0, 1, 0i = h1, 0, 1i,

y

H1, 0, 0L

x

H1, 2, 0L

and the plane is h1, 0, 1i · hx − 1, y, zi or x + z = 1.

I

(b) (3 points)

F · dr.

Calculate

C

Solution:

While we could parameterize the four segments of curve C, it is simpler to

apply Stokes’ Theorem and compute a flux integral instead. We orient the surface S to be

compatible with the orientation of C (that is, with the downward pointing normals). A simple

parameterization is r(x, y) = hx, y, 1 − xi (using the equation of the plane z = 1 − x found in

part (a)). Then S is the surface parameterized by r for points (x, y) in the region R, shown

below:

y ..............

....

...

.

..

...

.....

...

.......

...

.............

.

...

............

...

..............

...

................

... ......................................

... ......................

.............

.......................................

.............

.......................................

..........................

.............

.......................................

..........................

..........................

.............

.......................................

..........................

.............

......................................................................................................

..

..

...

....

.... ...

.

.

.. ..

....

..

.

.

.

.

..

.

1 ..

..

...

... R ...

...

.

.................................

2

1

x

Then rx × ry = h1, 0, 1i is precisely the cross product found in part (a). (Notice this is the

wrong orientation; we’ll use ry × rx = h−1, 0, −1i instead.) Using curl F = h1, 0, 0i, we get via

Stokes’ Theorem:

I

ZZ

ZZ

Z 1 Z 1+x

3

F · dr =

curl F · dS =

h1, 0, 0i · h−1, 0, −1i dy dx =

−1 dy dx = − .

2

C

S

R

0

0

ZZ

(c) (3 points)

curl F · dS.

Calculate

S

Solution: We’ve already computed this integral, assuming that S has the orientation we

gave it in part (b). If S is given the opposite orientation (with upward-pointing normals), this

would simply change the sign of our computation in part (b) and we’d get + 32 .

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

y

11 (10 points)

2

ZZ

(a) (4 points)

f (x, y) dA, where D is the region

Write

D

shown to the right, as an iterated integral of the form

Z b Z g2 (x)

f (x, y) dy dx.

a

Spring, 2009

.....

..........

...

....

..

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

....................

.....

..

...

..

...

...

...

...

.

............................................................................................................................................

...

.

g1 (x)

√

Solution:

The line has equation xy = tan( π3 ) = 3 or

√

y =

3x; this intersects

the circle at the point (x, y) =

√

π

π

3 3 3

(3 cos( 3 ), 3 sin( 3 )) = ( 2 , 2 ). Thus the integral can be written

as

Z

Z √

ZZ

x

9−x2

3/2

f (x, y) dA =

√

0

D

2

y =9

...........x.........+

..............

...

.........

..

....

...

...

.....

..

...

...

.

.

.

...

.

...

...

.

.

...

..

...

...

.

..

.

... π/6....

... ..

... .....

... ..

.......

...

f (x, y) dy dx.

3x

ZZ

(b) (4 points)

Write

f (x, y) dA as an iterated integral using polar coordinates.

D

Solution: The region D can be described in polar coordinates as those points with 0 ≤ r ≤ 3

and π3 ≤ θ ≤ π2 . Thus

ZZ

Z

π/2 Z 3

f (x, y) dA =

D

ZZ

(c) (2 points)

f (r cos(θ), r sin(θ)) r dr dθ.

π/3

Compute

0

cos(x2 + y 2 ) dA.

D

Solution:

We use polar coordinates as in part (b). We get

ZZ

2

Z

2

π/2 Z 3

cos(x + y ) dA =

π/3

D

cos(r2 ) r dr dθ

0

Z π/2

3

sin(9)

sin(r2 )

dθ =

dθ

2

2

π/3

π/3

0

sin(9) π π π

=

−

=

sin(9).

2

2

3

12

Z

=

π/2

Final Exam Solutions

Math 21a

Spring, 2009

12 (11 points) Let W be the solid tetrahedron with vertices (0, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), and (0, 0, 1).

This tetrahedron has volume 61 .

(a) (4 points) Let S be the surface that forms the boundary of W , oriented with the outwardpointing normal. Note that S has four pieces. Compute the flux of the vector field

3

F(x,

Z Z y, z) = (x − 3yz)i + (x + y)j + (tan(xy) + z)k out of the surface S. That is, compute

F · dS.

S

Solution:

We use the Divergence Theorem. There are two hints at why this might be

appropriate. First, computing the flux directly would require that we parameterize each of the

four pieces of S separately. Second, and perhaps even more importantly, the vector field F is

complicated and difficult to involve in an integral, while div F = 3. The Divergence Theorem

implies that

ZZ

ZZZ

ZZZ

1

F · dS =

div F dV =

3 dV = 3 Vol(W ) = ,

2

S

W

W

as we’re told the volume of W is 61 .

ZZ

(b) (3 points)

curl F · dS.

Compute the flux of curl F out of the surface S; that is, compute

S

Solution: Again we apply the Divergence Theorem. This time it’s even simpler, as we recall

that div (curl F) = 0 for any vector field F:

ZZ

ZZZ

ZZZ

curl F · dS =

div (curl F) dV =

0 dV = 0.

S

W

W

(c) (4 points)

Let S1 be the part of S that lies in the yz-plane (where

Z Z x = 0), oriented in the

same way as S. Find the flux of F through S1 ; that is, compute

F · dS.

S1

Solution:

below:

We parameterize S1 by r(y, z) = h0, y, zi where (y, z) lies in the region R shown

z ...............

...

1 .........................

............................

............................................

........................................................

.......................................................

. . . . . ....

.................................R

..............................................................................................................

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................

.....................

...

....

....

y

1

The normal rz × ry = h−1, 0, 0i is the proper orientation (outward from W ), so

ZZ

ZZ

F · dS =

0 − 3yz, 03 + y, tan(0y) + z · h−1, 0, 0i dz dy

S1

R

1 Z 1−y

Z

=

0

=

Z

3yz dz dy =

3

2

Z

0

0

1

0

1

3

2 y(y

1

y 3 − 2y 2 + y dy = .

8

− 1)2 dy