east africa regional conflict and instability assessment

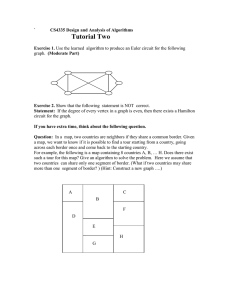

advertisement