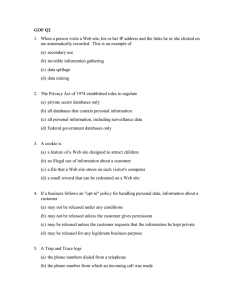

CCTV Code of Practice

advertisement