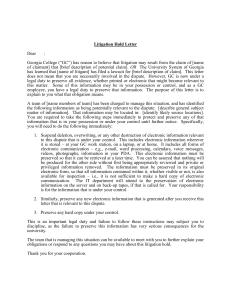

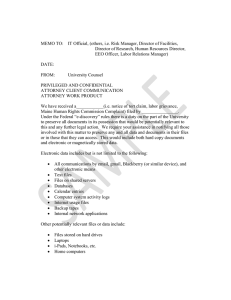

The Duty to Preserve Evidence

advertisement