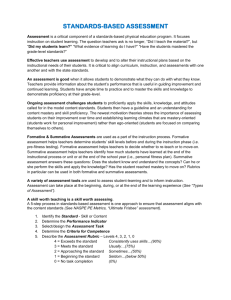

Standards-Based Teaching/Learning Cycle Guide

advertisement