L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012)

advertisement

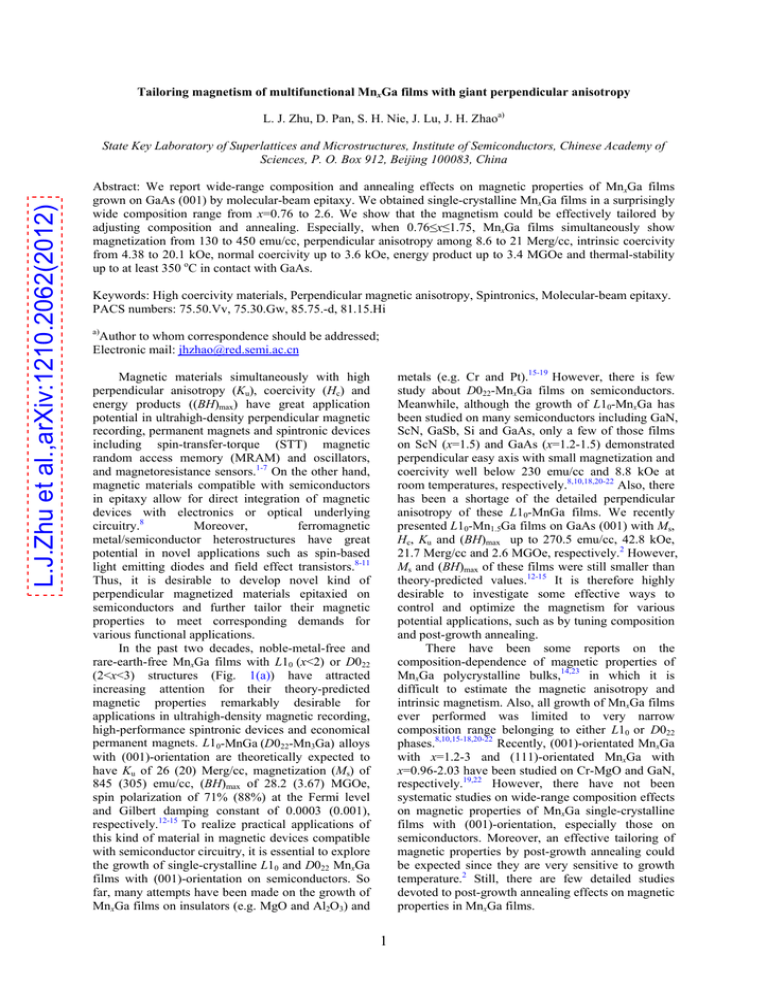

Tailoring magnetism of multifunctional MnxGa films with giant perpendicular anisotropy L. J. Zhu, D. Pan, S. H. Nie, J. Lu, J. H. Zhaoa) L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012) State Key Laboratory of Superlattices and Microstructures, Institute of Semiconductors, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P. O. Box 912, Beijing 100083, China Abstract: We report wide-range composition and annealing effects on magnetic properties of MnxGa films grown on GaAs (001) by molecular-beam epitaxy. We obtained single-crystalline MnxGa films in a surprisingly wide composition range from x=0.76 to 2.6. We show that the magnetism could be effectively tailored by adjusting composition and annealing. Especially, when 0.76≤x≤1.75, MnxGa films simultaneously show magnetization from 130 to 450 emu/cc, perpendicular anisotropy among 8.6 to 21 Merg/cc, intrinsic coercivity from 4.38 to 20.1 kOe, normal coercivity up to 3.6 kOe, energy product up to 3.4 MGOe and thermal-stability up to at least 350 oC in contact with GaAs. Keywords: High coercivity materials, Perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, Spintronics, Molecular-beam epitaxy. PACS numbers: 75.50.Vv, 75.30.Gw, 85.75.-d, 81.15.Hi a) Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; Electronic mail: jhzhao@red.semi.ac.cn metals (e.g. Cr and Pt).15-19 However, there is few study about D022-MnxGa films on semiconductors. Meanwhile, although the growth of L10-MnxGa has been studied on many semiconductors including GaN, ScN, GaSb, Si and GaAs, only a few of those films on ScN (x=1.5) and GaAs (x=1.2-1.5) demonstrated perpendicular easy axis with small magnetization and coercivity well below 230 emu/cc and 8.8 kOe at room temperatures, respectively.8,10,18,20-22 Also, there has been a shortage of the detailed perpendicular anisotropy of these L10-MnGa films. We recently presented L10-Mn1.5Ga films on GaAs (001) with Ms, Hc, Ku and (BH)max up to 270.5 emu/cc, 42.8 kOe, 21.7 Merg/cc and 2.6 MGOe, respectively.2 However, Ms and (BH)max of these films were still smaller than theory-predicted values.12-15 It is therefore highly desirable to investigate some effective ways to control and optimize the magnetism for various potential applications, such as by tuning composition and post-growth annealing. There have been some reports on the composition-dependence of magnetic properties of MnxGa polycrystalline bulks,14,23 in which it is difficult to estimate the magnetic anisotropy and intrinsic magnetism. Also, all growth of MnxGa films ever performed was limited to very narrow composition range belonging to either L10 or D022 phases.8,10,15-18,20-22 Recently, (001)-orientated MnxGa with x=1.2-3 and (111)-orientated MnxGa with x=0.96-2.03 have been studied on Cr-MgO and GaN, respectively.19,22 However, there have not been systematic studies on wide-range composition effects on magnetic properties of MnxGa single-crystalline films with (001)-orientation, especially those on semiconductors. Moreover, an effective tailoring of magnetic properties by post-growth annealing could be expected since they are very sensitive to growth temperature.2 Still, there are few detailed studies devoted to post-growth annealing effects on magnetic properties in MnxGa films. Magnetic materials simultaneously with high perpendicular anisotropy (Ku), coercivity (Hc) and energy products ((BH)max) have great application potential in ultrahigh-density perpendicular magnetic recording, permanent magnets and spintronic devices including spin-transfer-torque (STT) magnetic random access memory (MRAM) and oscillators, and magnetoresistance sensors.1-7 On the other hand, magnetic materials compatible with semiconductors in epitaxy allow for direct integration of magnetic devices with electronics or optical underlying Moreover, ferromagnetic circuitry.8 metal/semiconductor heterostructures have great potential in novel applications such as spin-based light emitting diodes and field effect transistors.8-11 Thus, it is desirable to develop novel kind of perpendicular magnetized materials epitaxied on semiconductors and further tailor their magnetic properties to meet corresponding demands for various functional applications. In the past two decades, noble-metal-free and rare-earth-free MnxGa films with L10 (x<2) or D022 (2<x<3) structures (Fig. 1(a)) have attracted increasing attention for their theory-predicted magnetic properties remarkably desirable for applications in ultrahigh-density magnetic recording, high-performance spintronic devices and economical permanent magnets. L10-MnGa (D022-Mn3Ga) alloys with (001)-orientation are theoretically expected to have Ku of 26 (20) Merg/cc, magnetization (Ms) of 845 (305) emu/cc, (BH)max of 28.2 (3.67) MGOe, spin polarization of 71% (88%) at the Fermi level and Gilbert damping constant of 0.0003 (0.001), respectively.12-15 To realize practical applications of this kind of material in magnetic devices compatible with semiconductor circuitry, it is essential to explore the growth of single-crystalline L10 and D022 MnxGa films with (001)-orientation on semiconductors. So far, many attempts have been made on the growth of MnxGa films on insulators (e.g. MgO and Al2O3) and 1 L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012) FIG. 1 (a) Lattice units of L10-MnGa (left) and D022-Mn3Ga (right), arrows stand for magnetic moment directions. Typical (b) XRR curves, (c) High-sensitivity XPS, (d) Synchrotron XRD patterns, (e) FWHM of MnxGa fundamental peaks, (f) Isup/Ifun and (g) c of MnxGa films. The blue arrows in (d) point to the (002), (003) and (004) peaks of MnGa4 phase appeared in the Mn0.55Ga and Mn0.74Ga. The c value for MnxGa bulks in ref. 14 (red ●) and ref. 23 (green ●) and films grown on GaN in ref. 21 (wine ●) are also plotted in (g), for comparison with films grown on GaAs (001) (wine O). In this letter, we present synthesis of (001)orientated single-crystalline MnxGa films with giant perpendicular anisotropy epitaxied on GaAs (001) in a surprisingly wide composition from x=0.76 to 2.6, and effective tailoring of the magnetic properties by controlling composition and annealing. These results would be much helpful for understanding this kind of materials and approaching functional applications in magnetic recording, spintronic devices and permanent magnets. A series of MnxGa films with different Mn/Ga atom ratio x were deposited at 250 oC on 150 nm-GaAs-buffered semi-insulating GaAs (001) substrates by molecular-beam epitaxy under base pressure less than 1×10-9 mbar.2 After cooling down to room temperature, each film was capped with a 1.5 nm-MgO layer to prevent oxidation. The composition was designed by carefully controlling the Mn and Ga fluxes during growth and later verified by high-sensitivity x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements (Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi) with Al Kα source and relative atomic sensitivity factors of 13.91 (1.085) for Mn 2p (Ga 3d). The thicknesses and crystalline structures of the films were respectively determined by synchrotron radiation x-ray reflection (XRR) and x-ray diffraction (XRD) with wave length of 1.54 Å. The magnetization measurements were performed by superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUID) up to 5 T and physical properties measurement system (PPMS) up to 14 T. The annealing studies were performed at temperatures from 100 to 500 oC under vacuum below 110-8 mbar. Figure 1(b) shows typical XRR curves with the strong oscillations, suggesting sharp interfaces and good homogeneity of these samples. From XRR curves, the thicknesses were also determined to range from 35 to 50 nm. Figure 1(c) shows examples of high-sensitivity XPS of Mn 2p and Ga 3d in the MnxGa films. From XPS results, x was estimated to be 0.55, 0.74, 0.76, 0.93, 0.94, 0.97, 1.07, 1.13, 1.29, 1.42, 1.75 and 2.60, respectively. The asymmetry of these peaks should be attributed to the significant shielding effect to core levels by the high statedensity at the Fermi level due to the alloy nature of these films. Furthermore, no considerable peak shifts are observable for both the Mn 2p and Ga 3d spectrums in all these films because of the protection of MgO cap layers from oxidation. Figure 1(d) shows examples of XRD θ-2θ patterns of MnxGa films with different x. For x ≥ 0.76, only sharp (001) ((002)) superlattice peaks and (002) ((004)) fundamental peaks of L10 (D022) MnxGa films can be observed in the range from 20o to 70o besides the peaks of GaAs substrates, indicating that these are all (001)-textured single-crystalline films. For film with x=0.74, three small peaks irrelative to L10 (or D022) appear, which become dominating for film with x= 0.55. The new phase could be best fitted by cubic MnGa4 24 with enlarged c axis of 3.91 Å, while Mn2Ga5, MnGa6, Mn3Ga5 and Mn5Ga7 phase24, 25 are not the case here. Noticeably, the (001)orientated D022-Mn2.6Ga film is of very poor crystalline quality and chemical ordering, indicating that it is difficult to crystallize the metastable D022MnxGa with high quality on GaAs, even when the lattice mismatch is very small (~2.2%). The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of fundamental 2 L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012) composition range are magnetically phase-pure with perpendicular easy axis. Figure 2(b) shows typically both perpendicular and in-plane hysteresis loops of MnxGa films. The perpendicular M-H curves show square-like shapes, whereas in-plane curves exhibit almost anhysteretic loops and high saturation field even exceeding 14 Tesla. The strong difference between the perpendicular curves and in-plane curves reveals giant perpendicular anisotropy in these films. In consistence with XRD results, MnxGa films with x=0.55 and 0.74 exhibit weak perpendicular anisotropy with very close Mr-T and M-H curves in perpendicular and in-plane directions due to the coexisting of MnGa4 phase and L10-phase. Figures 3(a)-(c) display the x-dependent magnetic properties including squareness (Mr/Ms), Ms and Hc determined from the 300 K perpendicular MH curves of these 250 oC-grown films. The MnxGa films with x=0.97-1.75 exhibit high Mr/Ms exceeding 0.90; but those with x deviated from this range show dramatically decreased Mr/Ms, the tendency of which is just opposite to that of c in Fig. 1(g), indicating that Mr/Ms in this kind of material could be strongly affected by strains. As shown in Fig. 3(b), Ms decreases dramatically from 450 to 52 emu/cc with x increases from 0.76 to 2.60, which should be attributed partly to the increase of antiferromagnetic coupling between Mn atoms at different sites,12 partly to the increase of strains induced by short c axis.2,22 The maximum Ms of 445 emu/cc in Mn0.76Ga, is still below the calculated value of 845 emu/cc for stoichiometric L10-MnGa17 and experimental value of 600 emu/cc in 400-450 oC-annealed Mn1.17Ga grown on MgO 19 probably due to the low growth temperature. Hc climbs up from 4.38 to 20.1 kOe as x increases from 0.76 to 1.75, and then drops to 1.1 kOe at x=2.60. This change tendency is consistent well with that of Ku estimated in Fig. 3(d) following the method used in ref. 2. Ku exhibits large values from 8.6 to 21.0 Merg/cc in L10 range, while quickly degrades to 0.02 Merg/cc in D022-Mn2.6Ga because of increased disorder. As ever discussed,2,14 rare-earth-free and noblemetal-free MnxGa alloys are considerable for economical permanent magnet application. Since intrinsic coercivity Hc determined from M-H curves, normal coercivity HcB determined from B-H curves and magnetic energy products (BH)max are three key features of quality of permanent magnets, we further calculated HcB and (BH)max in Fig. 3(e) and (f). With increasing x in the phase-pure range, both HcB and (BH)max decrease nearly monotonically, corresponding to the decrease of Ms. The film with x = 1.07 exhibit the highest HcB and (BH)max of 3.6 kOe and 3.4 MGOe, respectively. The maximum of 3.4 MGOe is larger than that recent reported in Mn1.5Ga film (2.6 MGOe)2 and ferrite magnets (3 MGOe),3 which makes L10-MnxGa alloys with low Mn compositions still promising to be developed for cost-effective and high-performance permanent magnets applications. FIG. 2 (a) Temperature dependence of remanent magnetization (Mr) and (b) Hysteresis loops of Mn1.4Ga film measured at 300 K. FIG. 3 (a) Mr/Ms, (b) Ms, (c) Hc, (d) Ku, (f) HcB and (g) (BH)max of MnxGa films on GaAs (001) plotted as a function of x. peaks, the integrated intensity ratio of superlattice and fundamental peaks Isup/Ifun (proportional to ordering parameters) and out-of-plane lattice parameters c (c/2) of L10 (D022) MnxGa determined from the XRD results are summarized as a function of x in Figs. 1(c), (d) and (e), respectively. With exception of Mn2.6Ga which is of poor quality and ordering, MnxGa films with x ≥ 0.76 show comparable FWHM and Isup/Ifun, implying similar crystalline quality and long range ordering degree. These films exhibit much short c-axis than bulks with same compositions probably due to tensile strains from epitaxy with GaAs. c first drops dramatically, consistent with the trend in bulks14,23 and film on GaN21; while it slowly comes back toward bulk values when x further increases. This non-monotonic trend probably relates to both tensile strains from epitaxy on GaAs and complicated compositiondependence of high level of dislocation induced by strain relaxation (see Supplemental Information). Figure 2(a) shows an example of temperature dependence of perpendicular remanent magnetization (Mr) of MnxGa film deposited on GaAs (001) with Curie temperature of 630 K. In contrast, the in-plane Mr-T curves shows nearly zero Mr values in the whole temperature range (not shown here). The similar feature holds for all the films with x=0.762.60, revealing that all these films over the large 3 L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012) FIG. 4 (a) XRD of 10 min-annealed Mn0.76Ga films at different temperature. (b) Perpendicular hysteresis loops of Mn0.76Ga films annealed at 450 oC for different time. Annealing temperature Ta (blue O, 10 min) and time (red ●, 450 oC) dependence of (c) Mr/Ms, (d) Ms, (e) Hc, (f) HcB, (g) (BH)max and (h) Ku of Mn0.76Ga films. least 350 oC in respect to both structure and magnetic properties could still satisfy the demand of integration with metal-oxide-semiconductor transistors. It should be motioned that further annealing at 450 oC for a longer time would significantly affect the magnetic behaviors of Mn0.67Ga films as show in Fig. 4(b). We should attribute this change mainly to both the structural improvement of Mn2Ga layer and increasing Mn2As formed at the interface with substrates. As summarized in Figs. 4 (c)-(h), with annealing time increase from 10 to 60 min, Hc drops monotonically from 4 to 1 kOe; Ms increases from 445 to 700 emu/cc; the highest Mr/Ms≈1 and highest Ku were obtained after annealed at 450 oC for 20-30 min. Therefore, for typical L10-Mn0.76Ga film, annealing at 450 oC for 20-30 min would be helpful to applications like magnetic recording and STT devices which favor high Mr/Ms, Ms, Ku and moderate Hc at the same time. From the viewpoint of permanent magnet applications, the best should be annealing at 450 oC for 10-20 min since the largest HcB and (BH)max of 4.4 MGOe were obtained in this range. In summary, both the wide-range composition and detailed annealing effects on the structure and magnetic properties of perpendicularly magnetized MnxGa epitaxial films on GaAs (001) have been systematically investigated. We show that singlecrystalline MnxGa films with L10 or D022 ordering could be crystallized at 250 oC on GaAs along (001) direction in a surprisingly wide composition range from x=0.76 to 2.6. Noticeably, L10-ordered MnxGa Taking into consideration of all the magnetic properties in Fig. 3, low-Mn-composition L10 MnxGa films are more advantageous than those D022 film to be developed for applications in magnetic recording with areal density over 10 Tb/inch2, highperformance nanoscale spintronic devices like MRAM bits with size down to several nm and economical permanent magnet applications, since they simultaneously exhibit high Mr/Ms, Ms, Ku, Hc, HcB and (BH)max. In order to investigate the thermal-dynamical properties and further tailor the magnetic properties of MnxGa films, especially the Ga-rich singlecrystalline films, we performed post-growth annealing experiments taking L10-Mn0.76Ga film as an example, which also exhibits the largest Ms among all the as-grown films with different x (Fig. 2). Figure 4(a) shows XRD patterns of as-grown and 10 min-annealed Mn0.76Ga films, from which we found the Mn0.76Ga film itself is thermal-dynamically stable up to 450 oC, and could keep stable up to at least 350 o C in contact with GaAs. This result roughly agrees with previous report that MnxGa with x<1.5 should keep stable on GaAs below 400 oC.26 Interestingly, very weak Mn2As (003) peak as a result of interfacial reaction is observable by high-sensitivity synchrotron XRD measurement, which may be not detectable by common XRD with Cu Kα radiation. 26 As summarized in Figs. 4(c)-(h), all the magnetic properties only exhibit very weak dependence on Ta in the case of 10-min annealing even when a small mount of Mn2As formed at the interface after 450 oCannealing. Fortunately, the stable temperature of at 4 L.J.Zhu et al.,arXiv:1210.2062(2012) 8 films showed high Ms, Mr/Ms, Ku, Hc, HcB and (BH)max, which make this kind of materials favorable for applications in ultrahigh-density perpendicular magnetic recording, permanent magnets, highperformance spintronic devices. In contrast, D022Mn2.6Ga films exhibited lower perpendicular anisotropy and weaker magnetism due to poor quality and high disordering. Annealing studies revealed thermal-stability of MnxGa up to at least 350 oC in contact with GaAs and effective tailoring of magnetic properties by controlling the formation of Mn2As at the interface through prolonged annealing at 450 oC. These results would be much helpful for understanding this kind of material and approaching the functional applications in magnetic recording, spintronic devices and permanent magnets. M. Tanaka, J. P. Harbison, J. DeBoeck, T. Sands, B. Philips, T. L. Cheeks, and V. G. Keramidas, Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 1565 (1993). 9 C. Adelmann, J. L. Hilton, B. D. Schultz, S. McKernan, C. J. Palmstrøm, X. Lou, H. S. Chiang, and P. A. Crowell, Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 112511 (2006). 10 E Lu, D. C. Ingram, A. R. Smith, J. W. Knepper, and F.Y. Yang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 146101 (2006). 11 H. C. Koo, J. H. Kwon, J. Eom, J. Chang, S. H. Han, and M. Johnson, Science 325, 1515 (2009). 12 A. Sakuma, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 187, 105 (1998). 13 Z. Yang, J. Li, D. Wang, K. Zhang, and X. Xie, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 182, 369 (1998). 14 J. Winterlik, B. Balke, G. H. Fecher, C. Felser, M. C. M. Alves, F.Bernardi, and J. Morais, Phys. Rev. B 77, 054406 (2008). 15 S. Mizukami, F. Wu, A. Sakuma, J. Walowski, D. Watanabe, T. Kubota, X. Zhang, H. Naganuma, M. Oogane, Y. Ando, and T. Miyazaki, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 117201 (2011). 16 F. Wu, S. Mizukami, D. Watanable, H. Naganuma, M. Oogane, and Y. Ando, Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 122503 (2009). 17 H. Kurt, K. Rode, M. Venkatesan, P. Stamenov, and J. M. D. Coey, Phys. Status. Solidi B 248, 2338 (2011); Phys. Rev. B 83, 020405(R) (2011). 18 W. Feng, D. V. Thiet, D. D. Dung, Y.Shin, and S. Chob, J. Appl. Phys. 108, 113903 (2010). 19 S. Mizukami, T. Kubota, F. Wu, X. Zhang, T. Miyazaki, H. Naganuma, M. Oogane, A. Sakuma, and Y. Ando, Phys. Rev. B 85, 014416 (2012). 20 K. M. Krishnan, Appl. Phys. Lett. 61, 2365 (1992). 21 A. Bedoya-Pinto, C. Zube, J. Malindretos, A. Urban, and A. Rizzi, Phys. Rev. B 84, 104424 (2011). 22 K. Wang, A. Chinchore, W. Lin, D. C. Ingram, A. R. Smith, A. J. Hauser, and F. Yang, J. Cry. Growth 311, 2265 (2009). 23 T. A. Bither and W. H. Cloud, J. Appl. Phys. 36, 1501 (1965). 24 H.G. Meissner and K. Schubert, Z. Metallkd. 56, 523 (1965). 25 J. S. Wu and K. H. Kuo, Metall. Mater. Trans. A 28A, 729 (1997). 26 J. L. Hilton, B. D. Schultz, S. McKernan, and C. J. Palmstrøm, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3145 (2004). We gratefully thank G. Q. Pan at the U7B beamline of National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) and W. Wen at the U7B beamline of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) in China for their help with XRD and XRR measurements. This work was supported by the NSFC under Grant Nos. 60836002 and 10920101071. References C. Chappert, A. Fert, and F. N. V. Dau, Nature Mater, 6, 813 (2007). 2 L. J. Zhu, S. H. Nie, K. K. Meng, D. Pan, J. H. Zhao, and H. Z. Zheng, Adv. Mater. 24, 4547 (2012). 3 O. Gutfleisch, M. A. Willard, E. Brück, C. H. Chen, S. G. Sankar, and J. P. Liu, Adv. Mater. 23, 821 (2011). 4 S. Ikeda, K. Miura, H. Yamamoto, K. Mizunuma, H. Gan, M. Endo, S. Kanai, J. Hayakawa, F. Matsukura, and H. Ohno, Nature Mater. 9, 721(2010). 5 D. Houssameddine, U. Ebels, B. Delaët, B. Rodmacq, I. Firastrau, F. Ponthenier, M. Brunet, C. Thirion, J. P. Michel, L. Prejbeanu-Buda, M. C. Cyrille, O. Redon, and B. Dieny, Nature Mater. 6, 447 (2007). 6 F. B. Mancoff, J. H. Dunn, B. M. Clemens, and R. L. White, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 1879 (2000). 7 T. J. Nummy, S. P Bennett, T. Cardinal, and D. Heiman, Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 252506 (2011). 1 5