The Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium

advertisement

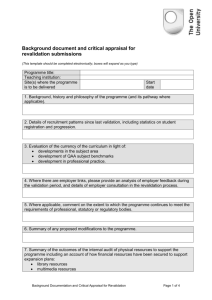

The Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium Sharing Best Practices, Lessons Learned Hosted by Federation of State Medical Boards (U.S.) General Medical Council (U.K.) Washington, D.C. October 7–8, 2013 Historic Meeting of International Regulators Contents Executive Summary2 Revalidation in the United Kingdom 4 Maintenance of Licensure in the U.S. 6 Continuing Professional Development Models from Australia, New Zealand and Ireland 8 Continuing Professional Development in the Canadian Provinces12 15 In the following pages of these proceedings of the Symposium is a series of fascinating progress reports from regulatory leaders in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and Canada. The proceedings conclude with several illuminating presentations addressing the role of medical specialty certification in the assessment of physicians, and lessons the medical profession can draw from the airline industry’s system of testing pilots. Never has it been more essential for medical regulators worldwide to work together to find solutions to the many common challenges we face. In times of volatility and change, we must learn to adapt — a process that is enhanced by our ability to connect and partner with others. We hope you find these proceedings helpful as this important conversation continues through the sharing of best practices and lessons learned. Sincerely, Humayun J. Chaudhry, DO, MS, MACP President and Chief Executive Officer Federation of State Medical Boards Niall Dickson Chief Executive and Registrar General Medical Council 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | Assessment Systems for Medical and Surgical Specialty Certification and Recertification, and in Other Industries Health care systems around the world face great challenges and uncertainty today as dramatic policy changes are implemented, demographic changes accelerate and new technological tools and infrastructure transform our work. With their critical role in the health care system of public protection, the world’s medical regulators are being challenged more than ever to innovate and adapt to address these challenges. This innovative spirit was clearly demonstrated at the Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium — the latest chapter of a growing worldwide movement in medical regulation to assure the public that doctors are competent and fit to practice throughout their careers. 1 Executive Summary Symposium identifies common ground and goal to ensure physician competence T h e S e c o n d I n t e r n at i o n a l “There is a lot of commonality in what we’re doing — how of these programs involve a major culture shift and Maintenance of Licensure/Revalidation Symposium, do we assure the public, which is what all medical regulatory they take time to implement. Sharing Best Practices, Lessons Learned, held on 7 and 8 authorities are about, of the continuing competence of October 2013 in Washington, D.C., brought together nearly physicians, regardless of what jurisdiction they practice in?” 40 participants from seven countries to continue a said Humayun Chaudhry, DO, President and CEO of the process that began three years earlier, of sharing experiences Federation of State Medical Boards. “As our nations embark in developing and implementing systems that assure the on these important measures, there is a lot to be shared. public that doctors are competent and fit to practice throughout This movement is growing; it is no longer confined to a handful their careers. of countries but is becoming a global issue.” Hosted jointly by the Federation of State Medical Boards (U.S.A.) Over the two days of the symposium, participants shared more and the General Medical Council (U.K.), participants sought to than a decade’s worth of regulatory experience and some of share lessons in their efforts to develop and implement systems the lessons learned on the way to developing their competence commonly referred to as Maintenance of Licensure, Revalidation, assurance programs. another hill in front of them.” Continuing Professional Development. • Continuing professional development should be the key Participants agreed that a continuing commitment to sharing motivator. The programs are not intended to be punitive, Although named differently across the world, participants but rather to encourage and enhance self-assessment, found that regulatory programs developed to assure reflection, lifelong learning, and professionalism. third symposium in Montreal, Quebec in October 2015 under • Communication with physicians, the public and key Regulatory Authorities. We look forward to seeing you there. Recertification, Maintenance of Professional Competence or physicians’ ongoing knowledge and skills within their respective countries have much more in common than expected. They are universally supported by a clear consensus that physicians basis. They are also a vital part of a broader international movement to improve the quality of health care and better assure patient safety. By fostering physician self-reflection and professional development, they directly support quality improvement across the profession. stakeholders are critical to the programs’ success. Dickson, Chief Executive and Registrar of the GMC, feels that becoming a global issue” • Governments are no longer asking “if” medical regulators are going to implement these systems but “when,” and are beginning to inquire about the results and impact of these and other initiatives aimed at improving standards in health care. “we’ve (the GMC) come a long way, but we are like the hill walker who reaches the top of the hill and realizes there’s best practices and information is critical to the ongoing growth and success of these initiatives and agreed to convene for a the auspices of the International Association of Medical As one meeting participant — Professor Kieran Murphy, former • Doctors are increasingly accepting that participating president of the Medical Council of Ireland — noted, “One in competence assurance programs is a requirement of of the advantages of these sorts of meetings is seeing that their profession and that participation in the process is of significant benefit to them. •The pace of progress is deliberately slow — there is a general understanding that the development and rollout — Humayun J. Chaudhry across the world there are many ways of doing the same thing.” 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2 should be able to demonstrate their competence on an ongoing With regards to the Revalidation program in the U.K., Niall “As our nations embark on these important measures, there is a lot to be shared. This movement is growing; it is no longer confined to a handful of countries but is 3 Revalidation in the United Kingdom The United Kingdom’s system of Revalidation was officially implemented in December 2012. Prior to Revalidation, doctors remained on the register indefinitely as long as they paid their annual fee and didn’t get into difficulties that led to referral to the General Medical Council (GMC) for investigation of their fitness to practice. It was up to doctors to remain up to date and maintain their fitness to practice. The GMC effectively relied on doctors’ innate professionalism to do what was right for their own development. Moderator: Niall Dickson, Chief Executive and Registrar, General Medical Council Presenters: Una Lane, Director, Registration and Revalidation, General Medical Council Michael Marsh, Medical Director and Responsible Officer, University Hospital Southampton —————————————————————————————— Una Lane Revalidation is about: • Finding and addressing potential problems earlier • Be based in training and education, not Human Resources • Be supportive and robust • Include well-trained appraisers “The concept of Revalidation is about having safety and quality of care at the core of the profession of medicine.” —Una Lane Most of the feedback the GMC received from doctors about engaging in Revalidation was that they were nervous about patient feedback. But most have discovered that patients are very positive. It is important for doctors to reflect on what patients are saying about them — “360 feedback” can be a little bruising but a lot of doctors have found it really useful. —————————————————————————————— Michael Marsh In terms of implementing a system like Revalidation, there must be recognition of the pressures and stresses of modern day health care. Doctors are busy, so they may not take the time to review information in detail. Therefore, myth busting is • Affirming a doctor’s professionalism important. Special efforts must be made to engage doctors • Good Medical Practice in the process and to help them understand that this is about improving quality, not a threat to their livelihoods. If doctors Revalidation is not about a point-in-time test or a pass/fail exam, don’t engage in this process, it’s worthless. A late start with nor is it about a new way to raise concerns with the GMC. It is also engagement is better than an early start without engagement. not the only purpose, or outcome, of appraisal of doctors. •Bringing doctors into a structured process and encouraging self-reflective practice The regulators can’t do this alone. The General Medical Council is dependent on the system — specifically, they’re dependent on the 800 legislatively-designated organizations that are responsible for conducting the annual appraisals of doctors participating in Revalidation. In turn, there is a huge amount of work involved for these designated organizations. Several fundamental principles for ensuring an organization’s readiness for Revalidation are that the process should: The benefits of Revalidation so far include higher quality appraisals, recognition of the importance and quality of patient feedback, an increased ability to deal with “difficult characters,” development of a culture of improvement, and a greater focus on personal development plans and patient outcomes. However, we are not sure if we are sufficiently robust in evaluating doctors; if we are effectively engaging with outside organizations to learn how to improve and be proactive; and if we are too distant from what is happening “on the ground.” We also recognize that some of the areas where we’re weakest is where the potential is greatest, e.g., locum doctors. • Challenge people when appropriate Lessons Learned / Best Practices • Have adequate appraisal support • The profession has to be with you. It’s very important to make an argument for Revalidation — it’s not enough for regulators to simply insist that it is proper and right for every doctor to do this. Even then, a number of things can hinder successful implementation, including: • Lack of leadership from the CEO, Board, and/or Responsible Officer • Conflicts of interest • Lack of an appraisal system and appraisers • Time required to complete the appraisal and portfolio • Data transfer between and among organizations • Prolonged rollout Frontline engagement and leadership at every level is critical, and the organizations need adequate resources to do the job. It is also important to make sure patients are engaged in the process. In the U.K., the public assumed there was a system already in place and were surprised when they found out there wasn’t. • We must make the purpose of Revalidation — a contribution to developing and improving clinical governance and quality of care — absolutely clear to the profession. It is part of a wider agenda of quality of care and patient safety. • It is important to get a basic model in place and make refinements over time. Where we start isn’t where we’ll end up. • This isn’t about individual doctors, but doctors being part of a wider team and part of the organizations they work for. • Consult, pilot and evaluate impact before roll out. •We must ensure Revalidation doesn’t drive individualism at the expense of teams. • Focus must be on patients and improving quality of care. 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 4 • Improving the governance of medical practice A key question to consider is whether Revalidation is about improving practice and moving the bell curve to the right or removing bad apples. These two ideas are not mutually exclusive. In the U.K., it’s about contributing to quality of care, but also about making a contribution to identifying poor performers much earlier to prevent patient harm. We hope Revalidation will drive many more doctors to properly begin to evaluate their practice in relation to their peers. It goes back to the core values of Good Medical Practice, which effectively set out values and principles we expect every doctor to meet — not just on the day they register, but continuously throughout their careers. 5 Maintenance of Licensure in the U.S. The Federation of State Medical Boards, consistent with policy originally adopted in 2004 and a framework adopted in 2010, continues its efforts to introduce a new system of ensuring the continued competence of licensed physicians through Maintenance of Licensure (MOL). A vital step on the path to MOL implementation by state medical and osteopathic boards in the United States is determining what impact this might have on state regulatory authorities and what professional development training tools — both new and existing — physicians could use to meet a state’s requirement for MOL. Feasibility studies to help evaluate these issues and to advance understanding of the MOL concept are currently underway in several states. Moderator: Humayun Chaudhry, DO, MACP, President and CEO, FSMB Presenters: Jon Thomas, MD, MBA, Chair, Federation of State Medical Boards Frances Cain, MPA, Assistant Vice President of Assessment Services, FSMB 70 medical board jurisdictions isn’t the goal anyone seeks, so some element of commonality is crucial for the success of MOL. The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) recognizes that MOL will be an evolving program and will take time and attention to be fully realized nationwide. —————————————————————————————— Frances Cain The FSMB is currently collaborating with other stakeholders to conduct state-level feasibility studies to advance understanding of the process, structure and resources necessary to develop an effective and comprehensive MOL system. Among the key areas that we are exploring include the readiness of a medical board to implement MOL; the potential impact on a state medical board’s license renewal process; and just as importantly, how do we support physicians’ participation in MOL? As we surveyed and listened to medical boards and practicing physicians, we expanded our thinking to include how we could support state boards and physicians in the overall broader system of continuing professional development (CPD). Through this process we have learned that communication is key to making sure the needs of both physicians and state medical boards are met as they explore implementation of MOL. Issues such as costs and potential negative impacts on the physician workforce (e.g., will older physicians retire rather than participate in MOL?) must be taken into account as state medical boards consider implementing MOL. Episodic opposition from state medical societies, difficulty in amending Medical Practice Acts, and turnover in state board members are also challenges to implementation. Mark C. Watts, MD, President, Colorado Medical Board —————————————————————————————— Jon Thomas, MD, MBA A unique challenge to implementing MOL in the United States is that there are 70 medical licensing authorities within the 50 states, each with its own governance structure, laws and regulations. Implementation of MOL may require amendments to some states’ Medical Practice Acts — their statutory authority for licensing and regulating doctors. Finding common language and standards will also be important. Currently, states seem to prefer working in a coordinated fashion, which is particularly relevant as more and more physicians are practicing in multiple states. Having 70 different MOL systems in each of the Currently, Colorado only has very basic and minimal requirements for medical license renewal — updating demographic information, an attestation that the licensee has malpractice insurance at prescribed levels, disclosure of certain legal charges and malpractice cases. Colorado is in the minority of states in that physicians are not required to complete CME (continuing medical education) as part of the license renewal process — in fact, it is statutorily prohibited. Implementation of MOL in Colorado would require a significant amendment to the state’s Medical Practice Act. However, there is a growing awareness that the state medical board should have a responsibility to ensure competence through regulation. This awareness is principally an outgrowth of the enormous amount of work done to craft a comprehensive opioid drug policy to address the prescription opioid drug crisis within the state. There is also recognition of the body of evidence pointing to, and supporting, the need for ensuring physicians remain competent throughout their careers and demonstrate a commitment to lifelong learning. Adoption of MOL would require significant legislative effort. Colorado’s legislature is grappling with multiple major issues. This year it had to respond to widespread damage caused by a series of state-wide hundred-year floods and the ongoing regulation of medical and recreational marijuana. In addition, there was a historically unprecedented recall of two legislators related to new gun control legislation. Currently, MOL seems like a “back burner” issue. It may be one that the legislature might be unwilling to tackle in the current legislative session. The medical board is part of a larger regulatory agency (the Department of Regulatory Agencies, or DORA), and as such, the board would need to obtain approval from DORA to implement any part of MOL that would require a legislative fix. As the board has looked at MOL, we have recognized that partnership with the state medical society is important. Due to a series of regulations, we as a board are unable to send out surveys, polls, or request feedback from our licensees with the renewal of their licenses. In addition, the medical board itself cannot introduce a bill into the legislature. Although DORA has a mechanism to introduce legislation, a limited number of bills can be introduced and many times these bills are fixes to existing legislation. Most recently the medical board worked closely with the state medical and osteopathic societies with the introduction of the FSMB’s MOL feasibility studies. The medical board will likely work closely with the societies on introduction of legislation to implement MOL. That would naturally require the full board’s approval. Communication is also critical. We have learned through our feasibility study work with FSMB that physicians in Colorado do not know much about MOL. While that is not necessarily a bad thing — it perhaps means that people do not have a preconceived notion about what MOL may mean — we have recognized the importance of communicating with frontline doctors about what MOL is really about. Some of the issues we are evaluating as part of a situational assessment in Colorado as we consider implementing MOL are: • How do you engage physicians? • Will MOL have an effect on disciplinary cases? • Is MOL part of the answer to other medical and healthcare-related issues in the state? •Does the protection gained by the public with MOL overcome the regulatory and financial burden to licensees? Lessons Learned / Best Practices • With 70 individual U.S. medical board jurisdictions, the MOL framework must be flexible enough to be easily adapted into the licensing processes of any state, but also must encourage uniformity from state to state with key overarching principles. • Continual communication with the physician community to “myth bust” misperceptions about MOL is critical. • Work closely with a small, manageable cross-section of boards to conduct feasibility studies that later can be adapted by boards across the country. • Make sure MOL programs are administratively nonburdensome to physicians and align as much as possible with CPD activities physicians are already engaged in. • Engage physicians at the grass-roots level through surveys and focus groups to gauge their understanding and/or misperceptions of MOL. • Through collaboration with key stakeholders, identify a wide array of easily accessible resources and tools for physicians to use to meet MOL requirements. 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 6 A rigorous process to gain initial licensure is in place in the United States, but there is very little required afterward of most physicians: they pay a fee and may be required to complete CME, but little else is required. From the public’s perspective, this is not appropriate. “One lesson we have learned over the past decade is that myths — for example that MOL will require physicians to take a high-stakes exam, or that state medical boards will require specialty board certification for license renewal — are persistent. Clear, continuous and consistent communication is important.” — Jon Thomas —————————————————————————————— Mark Watts, MD 7 “Communication with frontline doctors and partnership with state medical societies is critical.” — Mark Watts Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Models from Australia, New Zealand and Ireland There is a strong relationship between the medical regulatory authorities in New Zealand and Australia. Both countries also recognize Ireland as a “competent authority.” Therefore, physicians who graduate from medical schools in Ireland have virtually automatic entry into New Zealand and Australia as well. In recent years the medical regulatory authorities in these nations have recognized that the thinking about Continuing Professional Development is changing internationally toward a greater emphasis on systematic efforts to deliver educational interventions, and to encourage self-reflective practice and performance improvement over time. Above all, these CPD programs are intended to foster professionalism and ensure patient safety. Presenters: Moderator and Presenter: Philip Pigou, Chief Executive Officer, Medical Council of New Zealand Dr. Joanna Flynn, Chair of the Medical Board of Australia Professor Kieran Murphy, Former President, Medical Council of Ireland —————————————————————————————— Joanna Flynn give patients the assurance they seek that any doctor is competent and fit to practice, yet do so in a way that does not undermine trust and professionalism.” — Joanna Flynn • help keep the public safe by ensuring that only health practitioners who are suitably trained and qualified to practice in a competent and ethical manner are registered One way to begin to look at this is — If Revalidation is the answer, what is the question? • To address or prevent problems... —in competence/performance of individuals? —in trust and confidence in the profession? —in trust in the regulatory standards and processes? • facilitate provision of high quality education and training • Identifying “bruised apples”? • facilitate workforce mobility, access to care and enable the continuing development of a flexible health workforce • Assuring the public that “all apples” are good? Regulation of physicians is the responsibility of the Medical Board of Australia. The Medical Board has adopted a CPD Registration Standard by which physicians maintain, improve and broaden knowledge, expertise and competence and develop the personal qualities required in their professional lives. It requires a range of activities to meet individual learning needs, including practice-based reflective elements (e.g., audit, peer review or performance appraisal), as well as activities to enhance knowledge. The Medical Board also has other processes in place to assist in ensuring physicians’ ongoing competence and fitness to practice, including random audits of compliance with the CPD standard, declarations at the time of registration renewal regarding compliance with CPD standards, criminal history, etc. However, not all doctors are included in these processes, so that has led to a conversation about whether CPD is enough or whether we should move toward Revalidation in Australia. Although we are looking at the models and systems that are taking shape in other countries, we have said to the profession that we are not looking at a system akin to that in the U.K., because we have a much more public-private mix in Australia. However, we are grappling with the same questions raised by the U.K. and other countries. Similar to other countries, we have been asking ourselves some key questions, including: • What is the interface between professional regulation and health system regulation and clinical governance? • Is this diagnostic or developmental or both? • Is it for everyone or only for high risk groups? Or should we have screening for everyone and greater depth of requirements for those picked up on initial screen? • Should this be “point in time,” cyclical or a continuing evaluation? • Is this formative or summative? • Should there be a focus on testing or a focus on learning and demonstrating mastery? • What tools can assist physicians? We have been looking at multi-source feedback from patients, co-workers, colleagues; practice visits by peers; review of practice data; audit; self-assessment of knowledge; and formal testing of knowledge. • But, it must be recognized that the practice of medicine is complex and diverse and can’t be reduced to discrete, measurable outcomes • It is important not to harm the fragile trust people have in the profession by raising too many concerns about the profession, but equally important is that this is not an excuse to not address the problem. Ultimately, all of us are better professionals if we’re doing it because we intrinsically know that it is important to do rather than because someone is forcing us to do it. We want to encourage people’s professionalism rather than do anything that potentially harms it. We want to do something with intrinsic worth and that people find valuable and available around the country. ————————————————————————————— Kieran Murphy, MD, PhD “We should be trying to foster intrinsic motivation. The model shouldn’t be lots and lots of rules to force doctors into doing what they should be doing. It should be about providing a framework by which doctors can facilitate and fulfill their own inherent professionalism.” — Kieran Murphy We have identified some answers as well, though — • We must be clear that this is about a focus on patient safety • We will encourage self-reflective practice and improve performance of everyone over time and ensure minimum standards are met by all The Medical Council of Ireland is almost unique in that it has a very broad scope of responsibilities — accrediting all undergraduate and postgraduate training, registering doctors, investigating complaints and now ensuring all practitioners are competent and maintaining professional competence. 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 8 “The overall aim of our efforts is to In 2010, Australia moved to a single National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (National Scheme) for all registered health practitioners. The objectives of the National Scheme are to: 9 For a regulator to be competent and credible it must have the trust of the public and the profession. This is a tough line to walk as these are not necessarily opposing but challenging perspectives. Philosopher Onora O’Neill says that for a system to be seen as trustworthy by the public you have to actually demonstrate that you’re trustworthy, and you must demonstrate that you are vulnerable. Within the concept of regulation, as a regulator you must show that your processes are transparent and robust. And as a practitioner, you must demonstrate that you’re prepared to undergo a process that will demonstrate you are fit to practice. There is a high degree of trust in doctors in Ireland — they are rated by the public as the most trusted profession. The public has confidence in how well doctors do their jobs. However, we also know that studies show that as age increases, there is a higher chance of error creeping in. This brings us back to the issue of trust. Scandals within the health care system led to new legislation in Ireland in 2008. As a result, there is now a legal obligation for doctors to maintain their professional competence, and there is also a legal obligation on the medical council to ensure physicians’ competence. Our perspective is that the majority of doctors are already engaged in this voluntarily; this is just formalizing a process doctors have already been engaged in. • An assessment system is targeting the tail, the underperforming doctors. In Ireland, we have primarily a learning model. However, it is important to keep in mind that a system will always be dynamic and will not be cast in stone. A system should evolve. We have started a process that we have demonstrated is feasible and credible and well regarded by both the profession and public, but we would now hope to evolve that system to include more of the assessment elements. Doctors’ participation in the system is not just ticking a box, it’s much more formal. After assessing their needs, doctors plan their activities over the year, and then reflect on their performance and plan action based on that. The activities and processes need to be relevant to and integrated into doctors’ everyday practice. There is no point in having a wonderful system that is completely disconnected to doctors’ everyday practices. They have to see that it’s relevant to themselves rather than a bureaucratic exercise that is useless to them. Finally, we should be trying to foster intrinsic motivation. The model shouldn’t be lots and lots of rules to force doctors into doing what they should be doing. It should be about providing a framework by which doctors can facilitate and fulfill their own inherent professionalism. • Ensure professional leadership and build support • Hold workshops with patient representatives and doctors • Survey doctors to understand their views and concerns As we developed the system, we also recognized that we needed to determine what type of system this should be — learning or assessment: Philip Pigou The Medical Council of New Zealand’s (MCNZ) traditional approach to ensuring competence uses CPD as a proxy for ensuring competence. Since 1995, CPD — or Recertification as it was called in the legislation — has been mandatory for all New Zealand doctors and includes CME, peer review, and an audit of medical practice. The CPD has been based on self-directed learning with minimal peer assessment or guidance. Since 2008, however, the Council has recognized that thinking about CPD is changing internationally. There is greater emphasis on systematic and concerted efforts to deliver educational interventions, and how you identify what those interventions should be. For example, self-assessment is important, but what about doctors who don’t have the ability to accurately self assess? How do they get feedback in the development they need and want? The MCNZ’s regulation philosophy is that Council interventions should be targeted to situations where there is an elevated risk, and where the profession and other stakeholders may not be effective at mitigating that risk. There is an emphasis on profession-led development and on a “right touch” approach by the regulator. Our key principles are that: • All doctors should regularly assess and reflect on their performance with the assistance of their CPD provider • Review should be undertaken in a doctor’s own work environment and be tailored to their own practice • Start simple, basing our efforts on voluntary structures that work • Consult with all stakeholders on rules and standards ————————————————————————————— “In 2008, there were numerous questions about why we need to do this. Now we are moving to how we are going to do this.” — Philip Pigou The ultimate goal is to improve the quality of care that a doctor’s patients receive by facilitating the doctor’s professional development. We are currently drafting our future Vision, which includes the following: • CPD providers would be expected to offer tools which are intended to help doctors to reflect on their own practice and identify areas for improvement. The key difference between the current situation and the vision is that the Council would expect the providers to review the results of CPD activities with the doctor. • A tiered system with increased assistance for the provider if areas for improvement are identified. • Specific CPD targeted to doctors who may need increased assistance — a quality assurance approach. • A protocol that identifies the small number of doctors who require referral to the regulator where risk to public health and safety is identified. —————————————————————————————— Lessons Learned / Best Practices • To start, formalize professional responsibility and voluntary practice — use that as the basis for further development of the system. • Communicate, engage, and build support — with the profession and the public to ensure it is supported. If people on the ground don’t buy into it, it won’t go anywhere. • Keep things straightforward — doctors are very busy and don’t want to be burdened with a complicated system. • Ensure the system is practice-based. • The activity should link to a professional development plan for the doctor • Keep an eye to process and focus on outcomes. • Standards of the profession should be emphasized • Be honest about limitations. • Oversight and enforcement — must be built on trust. 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 10 Our overriding principle was to establish a system that was feasible and credible — we didn’t want to start with a very complex system that was destined to fail. Involving the profession in the development of the system was critical to its success. Consultation with the public and other stakeholders was also important. Some key steps we took were to: • A learning system is purely a CPD approach. The motivation is to shift the curve to the right and to raise the floor for all doctors. 11 Continuing Professional Development in the Canadian Provinces In Canada, there is a long history of work on this topic that serves as the foundation for the current work. This was formalized 20 years ago, when the registrars of the provincial and territorial colleges made a request to the Federation of Medical Licensing Authorities of Canada (now the Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities of Canada) to start working on a program to assure the maintenance of performance in physician practice. FMLAC then held a series of workshops with medical regulators and leaders to start working on a national strategy to build consensus on key terms and goals, and best practices. Moderator: Mark Staz, MA, Director, Continuing Professional Development, FSMB Presenters: Trevor Theman, MD, FRCSC, Registrar, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta Bill McCauley, MD, Medical Advisor in Practice Assessment and Enhancement, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario —————————————————————————————— Trevor Theman, MD In Canada, Revalidation focuses on demonstration of competent performance rather than just on competence. We believe the assurance of performance must be relevant to the physician’s practice. We want the process to be largely formative rather than summative, reflecting our view that what we’re seeing is a snapshot in time, and that the goal is continuing improvement over time. Currently, most Canadian jurisdictions require The concept of Revalidation in Canada began with a series of conferences in the 1980s, which led to development of the “wedding cake” model: • Step 1: screening of all physicians and subsequent feedback • Step 2: more in-depth review, such as peer review • Step 3: very detailed needs assessment. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta’s Physician Achievement Review (PAR) program, which has been in place since 1999, is aimed at accomplishing Step 1. The goal of PAR is to provide feedback to all physicians about their practice; to help identify learning needs and, when needed, to look more closely at a physician’s practice. The information gathered is confidential and entirely for the purpose of quality improvement; the tools have been created by peers and scientifically validated. Information from PAR is protected from the College’s complaint process, although the rules for its administration allow for the identification of a physician who is believed to be putting patients at risk. Findings from physicians who have participated in PAR indicate that 49% of participants said they made a change in their practice as a direct result of PAR. Most changes focused on aspects of patient care, communication with patients, colleagues and co-workers, and stress management. We think this is pretty profound. The feedback from colleagues, coworkers and the public is meaningful because physicians tell us they’ve made changes to their practice. And physicians care how they rate relative to their peers. We think the program has largely met its objectives. One of the most important outcomes — but one that is impossible to measure — is the value of PAR simply because we have it. We now have a profession with 9,000 practicing doctors in Alberta, and almost everyone undergoes PAR every five years; the profession accepts it. As we develop more tools and create more requirements for our members in terms of their demonstration of competent performance throughout their careers, the fact that we’ve gotten the profession to accept this is really important. Some of the critical success factors we have identified are: • Communication — frequent communication was essential; frequent messaging was needed to address various myths that arose • Goal — that this was meant as a pure quality improvement program “Our big goal is to do our best to raise the tide for everyone — because a rising tide lifts all boats. We also need to be aware there may be a small fraction of our membership that is putting our patients at risk and we need to identify and act on those.” — Trevor Theman We’ve also identified a number of issues and concerns: • Results not available to the regulator • Not the best assessment for the clinical expert role • Exemptions (numbers should be higher) •We understand physicians make changes to their practice as a result of assessment, but we’re not so sure how significant they are, how meaningful they are to patient outcomes, and how much it feeds into their continuing professional development • Frequency — only occurs once every five years • Interpretation of scoring •Results considered in isolation — not combined with other knowledge about the physician/practice Overall, though, we’ve found it’s doable. It isn’t cheap, but not too expensive either. It assesses certain competencies better than others, but we know it’s relevant and physicians make changes based on feedback. We know we can do this across the various domains of practice and that it works in various settings. We know that for the fraction of our membership that are flagged (about 10%), they get really good value. We’re not so sure the other 90 percent of our members who easily complete the review get the same value; that’s where we need to do more work. • Organizational support and buy-in In terms of what we would consider ideal, the following have been identified: • Clarity of purpose • Multiple and integrated sources of regular feedback • Instrument construction • Addressing all aspects of a practice • Logical, efficient processes • Relating to all roles (CanMEDS)/competencies • Testing — reliability, validity, utility, feasibility • Patient outcome information • Implementation — mechanics, feedback report, follow-up • Focused learning and measurable changes in practice • Reported to a “responsible agency” 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 12 Revalidation in Canada is based on the idea that physicians must remain competent throughout their careers. As regulators, we also believe that all physicians can benefit from continuous quality improvement. As in other countries, the public in Canada believed this was already being done. participation in CPD, and physicians are required to track and document CPD activities. The CanMEDS competencies/roles serve as the basis for the Canadian Revalidation system. 13 Assessment Systems for Medical and Surgical Specialty Certification and Recertification, and in Other Industries —————————————————————————————— Bill McCauley, MD We’re trying to develop a system in which physicians are regularly provided with feedback on their performance, either through activities they undertake themselves, or through activities they undertake with regulatory authorities, with their hospitals or colleagues — feedback that helps them know what they’re doing, how well their doing, and how they can improve. In many respects Canada is far down the road. We have a lot of tools that can be used, such as the PAR program; the Colleges of Ontario and Quebec have very robust peer assessment programs that have been in place for years. What we don’t have is a national framework. But we are in the early stages of developing one. In 2004, FMRAC sponsored a Revalidation Working Group, which developed a Revalidation definition and position statement: Revalidation Definition: “A quality assurance process in which members of a provincial/ territorial medical regulatory authority are required to provide satisfactory evidence of their commitment to continued competence in their practice.” Although this position was endorsed by FMRAC, a process did not exist. As a result, there has been fallout. Although multiple provinces now have mandatory CPD requirements (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec) as a direct result of the Revalidation position statement, many jurisdictions adopted or endorsed the statement but may not have a process in place. Similarly, while many jurisdictions are using mandatory multi-source feedback as part of their process, there is no national implementation strategy. Canada is much like the U.S. in that there are multiple (13) jurisdictions; it is possible to come up with an implementable national Revalidation process, but at this stage we’ve just started to think about that. FMRAC currently has a “Working Group on Physician Performance Enhancement” (WG-PPE), whose goal is to develop a pan-Canadian strategy for physician performance enhancement to help: • All practicing physicians in identifying opportunities for improvement Moderator: Jon Thomas, MD, MBA, Chair, FSMB Board of Directors General • All stakeholder organizations in identifying their roles and responsibilities in physician performance enhancement Presenters: • Communication; understanding Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA, President and Chief Executive Officer, American Board of Medical Specialties • Time, cost, administrative burden of participation Capt. (Ret.) Peter J. Wolfe, FRAeS, Executive Director, Professional Aviation Board of Certification •Relevance Manoj S. Patankar, PhD, FRAeS We have noticed, however, that certification and MOC is making a difference. For example, there is an increased focus on professionalism, including positive regard for push-style continuing education, improvements in simulation training and assessment, MOC is improving evidence-based decisions about laboratory testing, and MOC is impacting population health (e.g., pediatric screening and referral patterns, adult immunization). The Vision for the Working Group is that 1) Canadians are assured of the competence of physicians; and 2) physicians are supported in their continuous commitment to improve. Guiding Principles are also being developed — around WHO participates, WHAT should be assessed, HOW the assessments should be carried out, and WHAT resources need to be available post-assessment. The guiding principles describe a broad assessment framework that will allow 1) all physicians to receive feedback on their performance (primarily formative), 2) medical regulatory authorities to dig deeper when concerns are identified, and 3) stakeholders to participate using their areas of expertise. Questions and challenges remain in terms of developing and implementing a national Revalidation strategy — e.g., Would medical regulatory authorities and the public be sufficiently reassured if this process were in place?, How do we assess professionalism?, Authority rests with medical regulatory authorities and government, but is there universal buy-in to get a “National Strategy”? The Working Group will continue to develop recommendations to operationalize the Guiding Principles and to consider a Revalidation framework. This will include external consultation with all stakeholders and, ultimately, support of the medical regulatory authorities in their implementation of Revalidation. —————————————————————————————— Lessons Learned / Best Practices • CPD programs should focus on the demonstration of competent performance rather than just on competence — the assurance of performance must be relevant to the physician’s practice. •The key program used in some provinces identifying physicians with learning needs (Physician Achievement Review) is relevant to physicians — half of the physicians who participate make changes in patient care, commu­ nication with patients, colleagues and co-workers, and stress management as a direct result of their participation. • The program works across the various domains of practice and it works in various settings. For the fraction of our membership that is flagged during the process, they receive excellent feedback to help them improve. —————————————————————————————— Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA The mission of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) is to serve the public and the medical profession by improving the quality of health care through setting professional standards for lifelong certification in partnership with Member Boards. While ABMS and board certification is distinct from licensure to practice medicine, from specialty societies, and from medical education accreditation, it is part of the education/assessment/regulatory system that engages all of these organizations. •Change • Perceived conflicts of interest Proxy “The extraordinary opportunity for Maintenance of Certification is to positively impact the care of patients and communities, our national capabilities and outcomes, Unlike medical licensure, specialty board certification is a voluntary process. Following initial certification by an ABMS Member Board, physicians participate in continuing certification through a process called Maintenance of Certification (MOC). Currently: physician learning, and health care conversations; to support the social compact between the Public and Profession, and by doing so to help maintain medicine as a profession; and • More than 800,000 U.S. licensed physicians have initial ABMS Board Certification • More than 500,000 U.S. licensed physicians are participating in MOC programs to support physicians throughout their careers.” — Lois Margaret Nora For many years, the Board Certification process included initial certification only (i.e., a “diploma” or “point-in-time” model”). Over time, however, there was consensus to move to continuing certification. Three broad categories of anti-MOC sentiment were expressed during the transition to continuing certification: • Leadership makes a difference Specific aspects of the MOC program • ou cannot over-communicate • Prove it • The “why” is important • High stakes, secure exam • Changes the relationship between the Boards and the diplomates • Part IV requirements A number of valuable lessons learned have also been identified: • Change management and cultural change is difficult • Frequent communication is essential to address the various myths that arise about CPD programs. • Attention to the appropriate level (granularity) of the requirement • The program is economically viable. • Don’t require what is not available 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 14 Revalidation Position: “All licensed physicians in Canada must participate in a recognized revalidation process in which they demonstrate their commitment to continued competent performance in a framework that is fair, relevant, inclusive, transferable and formative.” • All medical regulatory authorities in identifying physicians who may benefit from focused assessment and enhancement 15 —————————————————————————————— Captain (Ret.) Peter J. Wolfe, Executive Director, Professional Aviation Board of Certification; and Manoj S. Patankar, PhD, FRAeS The Professional Aviation Board of Certification is an independent, non-profit organization serving as the certifying body responsible for professional airline pilot preparedness. It sets training standards for aspiring professional pilots, certifies (tests) pilots’ knowledge against those standards and has established criteria for keeping the certification current over time. The dominant process used today for the initial training and recurrent training of airline captains is called the Advanced Qualification Program (AQP), and is a significant change from previously prescriptive criteria that relied on counting classroom and flight hours, and event cycles (i.e., takeoffs and landings) as a measure of competency. AQP has identified the full spectrum of knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed by pilots and evaluates their performance in each subject and skill area over a threeyear cycle. AQP recurrent training includes classroom and online studies, simulator training and flight checks that confirm the pilots’ capability to exercise command authority and compliance with federal and company standards for aircraft and crew operations. AQP recurrent training also includes Line Oriented Flight Training ( LOFT), a series of simulator tests that include a complicated mix of scenarios such as mechanical problems, weather changes, medical emergencies, etc. — similar to some patient care issues — to train and assess crew responses to such events. Airlines have found the LOFT program to be extremely valuable because of its relevance and realism. It is important to note that the vast majority of the above reports come from voluntary safety programs that derive information from onboard flight data recorders that show what the airplane did at any given moment in the flight — but not why. The recorder data, coupled with narrative reports from the pilots of the flight enable the regulators, companies and pilots to draw high value information from an event that is then distributed as noted above. Trust is the key to the success of this incredibly effective safety system. This collaboration includes the regulator, the flight crew, the airline and a representative from the union. Everyone holds each other accountable for the integrity of this process, because they all understand that any breach of confidentiality in the system will cause an immediate cancellation of the entire process and the immediate loss of the many thousands of reports it has collected over its more than 20 years of operation. In 2012, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) — the aviation arm of the United Nations — created a set of core competencies, several of which are similar to ones identified by medical regulatory community. The ICAO wanted to identify the fact that training and checking should be performance and competency based and include a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes, with subsets of competencies that include observable behaviors. These will be published as a global guideline for airlines and represents a quantum leap in our industry in the endeavor to globally harmonize airline pilot training and assessment. Speaker Biographies Frances Cain is Assistant Vice President of Assessment Services for the FSMB and has responsibility for FSMB’s Maintenance of Licensure initiative. The Assessment Services department provides registration services for Step 3 of the United States Medical Licensure Examination and the Post-Licensure Assessment System, both of which are collaborative initiatives with the National Board of Medical Examiners to provide assessment tools to assist state medical boards in assessing physicians’ knowledge and competence for licensure purposes. Dr. Joanna Flynn is Chair of the Medical Board of Australia and a member of the Management Committee of IAMRA. A general practitioner in Melbourne, Victoria, Dr. Flynn has been involved in medical regulation for more than 20 years. In 2009 she was appointed the Inaugural Chair of the Medical Board of Australia, which is now responsible for registration and regulation of all doctors in Australia. Prior to 2010, Australia had medical boards in each state and territory. Dr. Flynn also has served as President of the Australian Medical Council, which is the independent national standards body for the country’s medical education and training, and she chaired the working party that developed the seminal ‘Good Medical Practice: A Code of Conduct for Doctors in Australia’ in preparation for the introduction of national medical registration. Una Lane, Director, Registration and Revalidation, General Medical Council, joined the General Medical Council in October 2002, taking responsibility for planning and implementing reforms to the GMC’s fitness to practice procedures. In 2010 she became Director of Continued Practice and Revalidation, successfully steering the GMC towards the implementation of Revalidation in 2012. She now leads the Registration and Revalidation Directorate. She previously worked at the Legal Services Commission and was responsible for the quality assurance program for legal aid practitioners and managing the Commission’s contracts with suppliers of legal services in London. Dr. Michael Marsh, Medical Director and Responsible Officer, University Hospital Southampton, is a consultant in Paediatric Intensive Care. In 1998 he was named Director of Paediatric Intensive Care at Southampton and led the development of the service. In 2006 he was appointed Clinical Lead for Child Health leading on the integration and modernization of paediatric services. In 2007 he became Divisional Clinical Director for Women and Children’s services. From 2002-2008 he served as Honorary Secretary for the Paediatric Intensive Care Society providing leadership and specialist advice on children’s intensive care. He assumed the position of Medical Director for University Hospital Southampton in 2009. Dr. Bill McCauley was appointed as Western University’s representative to the Council of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario in 2002 and he was subsequently hired by the College to serve on staff as a Medical Advisor in Practice Assessment and Enhancement. This position gives Dr. McCauley the opportunity to be involved in education and assessment program development both at the CPSO and through interaction with many external stakeholders to the College’s work. Dr. McCauley is the Past President of the Coalition for Physician Enhancement, and he continues to practice Emergency Medicine in London, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Jon Thomas is Immediate Past Chair of the FSMB and a Past President of the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice. He also is the President and CEO of Ear, Nose and Throat Specialty Care of Minnesota. Dr. Thomas was appointed to the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice in 2001 and was reappointed in 2005 and 2010. He has served on a variety of FSMB committees and task forces. continued on next page 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 2014 Second International MOL/Revalidation Symposium | 16 “Requalification” for pilots occurs before a pilot returns to line flying duties after taking personal, academic or medical leave for an extended period of time, i.e., a Family Medical Leave absence or a U.S. military member called up for duty for an extended period. Requalification requirements, again, are set on a caseby-case basis. A pilot may only have to successfully complete the company’s recurrent training program or, for extensive absences, may have to complete the entire initial qualification course for new hire pilots. The intent is to bring the pilot up to speed and make sure he or she is ready to safely resume flying. The training curriculum is largely driven by data provided by a wide range of safety reports from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), mechanical reports from manufacturers, and the safety management systems (SMS) of the pilots’ respective companies. Airlines continually receive reports about safety issues that occur within their respective organizations, as well as aggregate and de-identified data from across the industry. As this information comes in, each carrier incorporated the lessons learned into courses, special training modules/ events, operating procedures and checklists. 17 continued on back page Speaker Biographies continued from previous page Dr. Kieran Murphy was appointed to the Medical Council of Ireland in 2004. He was subsequently elected President in 2008 and served a five-year term which concluded earlier this year. In 2012, he was elected to the Management Committee of IAMRA, and earlier this year he was appointed to the Council of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland, the country’s pharmacy regulator. In 2002, he began his current appointment as Professor and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry for the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and as Consultant Psychiatrist in Dublin. He runs a Behavioural Genetics Service in association with the National Centre for Medical Genetics and also a tertiary-level Neuropsychiatry service in association with the National Neuroscience Centre. Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA President and Chief Executive Officer Dr. Lois Margaret Nora is President and CEO of the American Board of Medical Specialties. The mission of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) is to serve the public and the medical profession to ABMS, Dr. Nora served as Interim President byPrior the quality of health care andimproving Dean of The Commonwealth Medical College (TCMC) in Scranton, Pennsylvania, one of the nation’s through setting professional standards forleadership, lifelong certification newest medical schools. Under Dr. Nora’s TCMC achieved major milestones en route to fulfilling promise to improve health careDr. in northeastern in partnership with itsMember Boards. Nora has more than Pennsylvania through innovative, community-focused, patient-centered, medical education. From 2002-2010, Dr. Nora served as with a career 20 yearsevidence-based of experience in academic medicine, President and Dean of Medicine at Northeast Ohio Medical University (then NEOUCOM). During Dr. Nora’s tenure, institutional accomplishments included the founding of a College of including roles as clinician, teacher, scholar, medical school Pharmacy and College of Graduate Studies; a founding partnership in the Austen BioInnovation Institute in Akron; and selection as one ofPrior Ohio’s best workplaces, among others. Previously, president and dean. to joining ABMS, Dr. Nora served as Dr. Nora served as Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Administration and Professor of Neurology at thePresident University of Kentucky College of Medicine, and Assistant Dean and Assistant Medical Interim and Dean of The Commonwealth Professor of Neurology at Rush Medical College in Chicago. College in Scranton, Pennsylvania, one of the nation’s newest Dr. Nora’s scholarly work focuses on issues in medical education, particularly the student environment, and issues at the intersection of law and medicine. Her honors include the medical andPresident’s from Recognition 2002-2010 American Medicalschools, Women’s Association Award, theshe AAMCserved Group on as President Educational Affairs Merrel Flair Award in Medical Education, The Phillips Medal of Public Service and Dean of College Medicine at Medicine, Northeast Ohio Medical University. from the Ohio University of Osteopathic and the 2010 Northeast Ohio Dr. Lois Margaret Nora is President and Chief Executive Officer of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). ABMS is a not-for-profit organization that supports its 24 medical specialty Member Boards in developing and implementing educational and professional standards to certify physician specialists and encourage lifelong learning and assessment. Through these efforts, ABMS helps ensure high quality health care for patients, families and communities. Medical University College of Pharmacy Dean’s Leadership Award, among others. Dr. Nora received her medical degree from Rush Medical College, a law degree and certificate in clinical medical ethics from the University of Chicago and a Master of Business Administration degree from the University of Kentucky Gatton College of Business and Economics. Philip Pigou has been Chief Executive Officer of the Medical Council of New She is Board Certified and participating in Maintenancesince of Certification in neurology the Zealand 2005 andbyserved as Chair American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. of the International Association of Medical Regulatory Authorities from 2012-2014. He has a background in strategy and change management, introducing a strategic program in the Medical Council. He has also led major initiatives in primary health care in New Zealand. Dr. Trevor Theman was elected to the Council of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta and served two terms as Council President prior to accepting a position as an Assistant Registrar for the College’s complaints department. This position sensitized Dr. Theman to the systems of care in which physicians and other health care workers practice, and led to his interest in patient safety. Dr. Theman assumed the position of Registrar in 2005. He is a keen advocate of quality and measurement in medical practice, and believes that the future of medical regulation is in the use of databases to proactively monitor processes and outcomes around quality patient care. Dr. Mark Watts earned his BA in Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry from Yale University in 1986 and he earned his medical degree from Stanford University School of Medicine in 1991. Dr. Watts then went on to a general surgery internship and neurosurgical residency at The Johns Hopkins Hospital under then Chairman Dr. Donlin Long. He also completed his two-year fellowship in Neuro-Oncology at Johns Hopkins under the direction of Dr. Henry Brem. In 2004 he accepted a position with Kaiser Permanente and he joined the staff at Exempla Saint Joseph Hospital. In 2008 Dr. Watts was appointed Vice-Chair of Surgery at St. Josephs and in 2011 he was subsequently appointed Chief of Surgical Services and Medical Director of the Operating Room and Perioperative Services. In 2007 Dr. Watts was appointed by the Governor to the Colorado Medical Board, where he currently serves as Immediate Past President. Captain Peter Wolfe is the Executive Director of the Professional Aviation Board of Certification. PABC is an independent, non-profit organization now being developed to serve as the worldwide certifying body responsible for assuring the preparedness of pilots to enter qualification training for employment by commercial and business air services. PABC sets the global pre-employment standards for knowledge training, and tests candidate pilots against those standards. Previously, Captain Wolfe served at Southwest Airlines as a line pilot and human factors specialist for Flight Operations. A retired U.S. Air Force colonel, he held a variety of staff and command positions involving flight operations, safety, maintenance and training, including duty as the Assistant Director of Operations for the North American Air Defense Command.