Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of

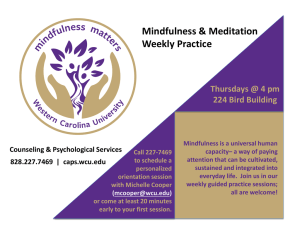

advertisement