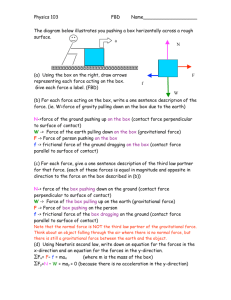

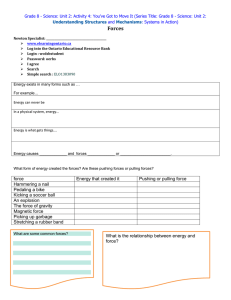

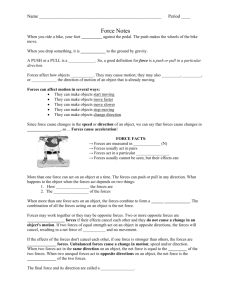

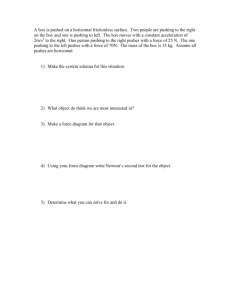

Pushing, pulling and applying force

advertisement