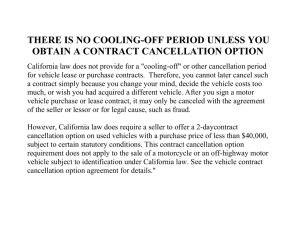

Cooling-off periods in Victoria: their use, nature, cost and implications

advertisement