as a PDF

advertisement

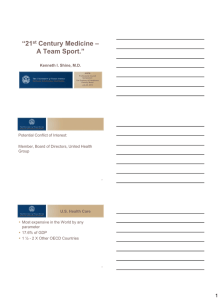

DISEASE MANAGEMENT Volume 11, Number 1, 2008 © Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/dis.2008.111723 Guided Care: Cost and Utilization Outcomes in a Pilot Study MARTHA L. SYLVIA, R.N., M.S.N., M.B.A.,1 MICHAEL GRISWOLD, Ph.D.,2 LINDA DUNBAR, Ph.D.,1 CYNTHIA M. BOYD, M.D., M.P.H.,2,3 MARGARET PARK, M.P.H.,2 and CHAD BOULT, M.D., M.P.H., M.B.A.2,3 ABSTRACT Guided Care (GC) is an enhancement to primary care that incorporates the operative principles of disease management and chronic care innovations. In a 6-month quasi-experimental study, we compared the cost and utilization patterns of patients assigned to GC and Usual Care (UC). The setting was a community-based general internal medicine practice. The participants were patients of 4 general internists. They were older, chronically ill, communitydwelling patients, members of a capitated health plan, and identified as high risk. Using the Adjusted Clinical Groups Predictive Model® (ACG-PM), we identified those at highest risk of future health care utilization. We selected the 75 highest-risk older patients of 2 internists at a primary care practice to receive GC and the 75 highest-risk older patients of 2 other internists in the same practice to receive UC. Insurance data were used to describe the groups’ demographics, chronic conditions, insurance expenditures, and utilization. Among our results, at baseline, the GC (all targeted patients) and UC groups were similar in demographics and prevalence of chronic conditions, but the GC group had a higher mean ACG-PM risk score (0.34 vs. 0.20, p 0.0001). During the following 6 months, the GC group had lower unadjusted mean insurance expenditures, hospital admissions, hospital days, and emergency department visits (p 0.05). There were larger differences in insurance expenditures between the GC and UC groups at lower risk levels (at ACG-PM 0.10, mean difference $4340; at ACG-PM 0.6, mean difference $1304). Thirty-one of the 75 patients assigned to receive GC actually enrolled in the intervention. These results suggest that GC may reduce insurance expenditures for high-risk older adults. If these results are confirmed in larger, randomized studies, GC may help to increase the efficiency of health care for the aging American population. (Disease Management. 2008;11:29–36) BACKGROUND ciaries have at least 1 chronic condition, 63% have 2 or more, and 20% have 5 or more.2 The United States currently spends more than 75% of its $1.4 trillion health care budget on chronic disease.3 A strong association exists between the number of chronic conditions and the like- B Y 2010, 141 MILLION AMERICANS are expected to be living with at least 1 chronic condition, and 70 million will have multiple chronic conditions.1 Already, 78% of Medicare benefi1Johns Hopkins HealthCare, Glen Burnie, Maryland. Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland. 3Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. 2Johns 29 30 lihood of hospitalization and overall health care utilization. The number of chronic conditions is related to per capita annual medical costs, increasing from $163 for those with no chronic conditions to $13,730 for those with 5 or more conditions.2 Currently, 24% of Medicare beneficiaries account for 80% of Medicare’s total health care spending.2 Not only are individuals with 4 or more chronic conditions more likely to be hospitalized, they are 99 times more likely to have potentially preventable hospitalizations.4 Today’s acute-care-focused health care delivery system, which emphasizes the treatment of episodic events, is not designed to deliver the type of chronic care needed by the majority of older Americans who have complex chronic conditions.5,6,7,8 With this system, people with chronic illnesses often find it challenging to get the necessary support to manage their conditions, obtain treatment, prevent complications, and participate in their care plans.9 To improve quality of life for older adults with multimorbidity and complex care needs and promote the efficient use of resources, we designed an enhancement to primary care. Guided Care (GC) is primary health care infused with the operative principles of recent innovations to ensure optimal outcomes for patients with chronic conditions and complex health care needs. A registered nurse who has completed a supplemental educational curriculum works in a practice with several primary care physicians (PCPs) to provide costeffective chronic care to 50 to 60 multimorbid patients. Using a Web-accessible electronic health record (EHR), the guided care nurse (GCN) collaborates with the patient’s PCP in conducting 8 clinical processes: assessing the patient and primary caregiver at home, creating an evidence-based care plan, promoting patient self-management, monitoring the patient’s conditions monthly, coaching the patient to practice healthy behaviors, coordinating the patient’s transitions between sites and providers of care, educating and supporting the caregiver, and facilitating access to community resources. A more detailed description of GC has been published previously.10 SYLVIA ET AL. In 2003–2004 we conducted a pilot study of a partial version of GC, in which the chronic disease self-management classes and the caregiver education and support components were omitted because of budgetary constraints. We sought to compare the cost and utilization patterns of patients assigned to receive GC and those assigned to receive Usual Care (UC). METHODS Study design We conducted a quasi-experimental study of the partial version of GC. Four general internists at an urban community practice were assigned to provide either GC or UC to their highest risk patients aged 65 years or older who were enrolled in a capitated health plan with benefits similar to Medicare. We used insurance information and a predictive modeling algorithm, the Adjusted Clinical Groups Predictive Model® (ACG-PM), part of the Johns Hopkins ACG® Case Mix System, to identify these physicians’ high-risk patients for the study.11 ACG-PM software analyzes health insurance enrollment records and diagnostic information from claims to compute the probability that patients will generate insurance expenditures that will rank within the highest 5% of the population during the following year. Values of R2 in ACG performance studies measuring costs or utilization as the outcome variable vary between 0.07 and 0.23, which is consistent with the performance of other similar predictive models.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 C-statistic results for the ACG system in predicting utilization outcomes vary between 0.69 and 0.73 depending on the outcome measured.18,21,22 Through insurance records, we observed each participating patient’s use and cost of health services for 6 months. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved the study. Intervention One GCN was assigned to work with 2 of the physicians and their high-risk older patients. GUIDED CARE OUTCOMES The GCN completed a 25-module curriculum covering chronic disease management (ie, depression, falls, congestive heart failure, diabetes, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, angina, dementia, osteoporosis, and constipation), patient preferences, case management, geriatric assessment and care planning, transitional care, information technology, patient education, ethnogeriatrics, community resources, communication with physicians, and insurance benefits. The GCN then underwent a 3-month integration into the practice by working with the 2 GC physicians and their office staff. After the integration phase, the GCN began contacting the high-risk patients of the 2 physicians by phone to schedule times to conduct initial assessments in the home. When caregivers were identified, they were encouraged to be present. During October 2003–March 2004, the GCN visited each patient’s home to assess the patient’s medical, functional, cognitive, affective, psychosocial, environmental, and nutritional characteristics. The GCN enrolled 31 of the 75 identified high-risk patients into her caseload during this period. Reasons for nonenrollment included death, moving out of the area, changing PCP, and already being enrolled in a case or disease management program. The GCN and the PCP worked collaboratively with the patient and caregiver to develop a care guide that incorporated relevant “best practice” guidelines for each of the patient’s conditions. The GCN, who was based in the primary care practice, then provided regular monitoring and coaching, transitional care, care coordination, and access to community resources in collaboration with the 2 PCPs. Measures From the health plan’s enrollment data and insurance claims, we obtained information about participating enrollees’ baseline characteristics and about the health plan’s subsequent expenditures for their health care services. The utilization and expenditure data were not adjusted for inflation. Total expenditures included all costs incurred by the health insurer for all fee-for-service care. Primary care, labo- 31 ratory, and radiology services, which were capitated by the health plan, were not included. Pharmacy costs also were excluded because health plan enrollees used multiple pharmacy benefit providers within and outside of the health plan. Utilization outcome measures included hospital admissions, hospital days, and emergency department (ED) visits (except those that resulted in a hospital admission). We used the ACG-PM software to categorize International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic codes submitted with the insurance claims to estimate the prevalence of the chronic conditions shown in Table 1. Statistical analysis We analyzed the data using an “intent to treat” (ITT) framework, thus including all patients assigned to receive GC or UC. We used the ITT approach as a primary method to compare cost savings to account for those unmeasurable factors, such as adherence and compliance, that made GC-assigned patients likely to take up the intervention. ITT is considered one of the best ways to ensure that evaluation results are unbiased by these unmeasurable factors.23 For demographic comparisons of the GC and UC groups, we used histograms, boxplots, t-tests, and chi-square statistics to evaluate ACG-PM scores, gender, age, and disease prevalence. Insurance expenditures, hospital admissions, hospital days, and ED visits were compared between the groups. Nonparametric smooth mean response curves were used to explore the relationships between costs and continuous variables, and a regression plateau model was developed accordingly to quantify the trends in expenditure differences between groups across increasing ACG-PM risk levels, adjusting for age and gender.24 The regression plateau model is a special case of a linear spline regression model, which parameterizes a leveling off of the mean response past a given cut point after adjusting for other confounding variables.25 Here, the empirical “leveling off” observed in the exploratory smoothed response curves captures a biological effect of a similarity in illness burden across the range of higher ACG-PM scores. 32 SYLVIA ET AL. TABLE 1. BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS GC (n 62) UC (n 65) p-value* Demographics Age, mean Female ACG-PM, mean 74.1 60.3% 0.34 75.8 47.7% 0.20 .7620 .1241 .0001 Health status Ischemic heart disease Congestive heart failure Hypertension Diabetes Osteoarthritis Parkinson’s Disease Dementia Depression COPD Chronic conditions, mean (total of 9) 51.6% 30.7% 88.7% 29.0% 48.4% 1.6% 8.1% 12.9% 19.4% 2.9 49.2% 21.5% 86.2% 20.0% 46.2% 7.7% 13.8% 18.5% 21.5% 2.9 .7884 .2421 .6644 .2362 .8011 .1065 .2984 .3900 .7605 .8204 *Chi Square for categorical variables, Student’s t-test for continuous variables. GC, guided care; UC, usual care; ACG-PM, Adjusted Clinical Groups Predictive Model; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. RESULTS Sixty-two GC-assigned and 65 UC-assigned patients remained enrolled in the health plan for 6 months and were included in this analysis. At baseline, the GC- and UC-assigned patients were similar in age, gender, number of chronic conditions, and chronic condition prevalence (Table 1). GC-assigned patients, however, had a significantly higher mean TABLE 2. ACG-PM risk score than UC-assigned patients (0.34 vs. 0.20, p 0.0001). Unadjusted and adjusted expenditure differences between GC and UC groups are reported. Table 2 shows the unadjusted mean insurance expenditures and utilization of health care services by the GC and UC groups. Despite the higher baseline risk of utilization, the GC-assigned patients had lower insurance expenditures; fewer hospital admissions, hospital days, UNADJUSTED MEAN TOTAL 6-MONTH EXPENDITURES AND UTILIZATION Mean (95% CI) Total insurance expenditures Hospital admissions Hospital days Emergency department visits Primary care visits GC (n 62) UC (n 65) p-value* $4586 ($2678, $6493) $5964 ($3759, $8171) 0.347 0.24 (0.09, 0.39) 0.43 (0.19, 0.67) 0.185 0.82 (0.15, 1.49) 2.45 (0.60, 4.30) 0.103 0.15 (0.00, 0.32) 0.31 (0.12, 0.49) 0.200 5.2 (4.01, 6.37) 4.9 (3.93, 4.88) 0.676 *Student’s t-test CI, confidence interval; GC, guided care, UC usual care. GUIDED CARE OUTCOMES 33 Six-month Insurance Expenditures 40000 30000 UC GC 20000 UC (N⫽65) GC (N⫽62) 10000 0 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Baseline ACG-PM 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 FIG. 1. Estimates from the regression plateau model, comparing 6-month insurance expenditures for the usual care (UC) and guided care (GC) recipients with different ACG-PM scores. Mean Difference Between Six-month Insurance Expenditures for UC and GC groups and ED visits; and more primary care visits than UC-assigned patients. However, these results were not statistically significant. The relationship between baseline ACG-PM levels and subsequent expenditures is shown in Fig. 1. Smoothed regression techniques suggested a linear relationship in both groups between baseline ACG-PM and total expenditures. The UC-patients had higher costs than the GC-patients when ACG-PM scores were 0.6. This relationship was difficult to evaluate at ACG-PM scores greater than 0.6 because of the small number of patients. Fig. 2 shows that the mean expenditure differences between the GC and UC groups were greater at lower baseline ACG-PM scores, after adjusting for age and gender. These differences were statistically significant at lower ACG-PM scores. $10,000 $8,000 $6,000 $4340 $3733 $1910 $2518 $3126 $1304 $4,000 $2,000 $0 P⫽0.04 P⫽0.02 -$2,000 P⫽0.06 P⫽0.27 -$4,000 P⫽0.54 -$6,000 P⫽0.75 -$8,000 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 Baseline ACG-PM 0.5 0.6 0.7 FIG. 2. Mean differences (with 95% confidence interval) in 6-month insurance expenditures between guided care and usual care groups at increasing baseline ACG-PM scores, adjusted for age and gender. 34 SYLVIA ET AL. Six-month Insurance Expenditures Cost 40000 30000 UC GC-received GC-assignedbut-not-received 20000 GC-received (n⫽31) 10000 UC (n⫽65) GC-assignedbut-notreceived (n⫽31) 0 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Baseline ACG-PM 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 FIG. 3. Nonparametric smooth response curves showing usual care (UC), guided care (GC)-received, and guided care (GC)-assigned-but-not-received expenditures with different baseline ACG-PM scores. Until this point, cost and utilization differences have been reported for all “targeted” patients; however, of the patients assigned to the GC group, 31 actually received GC. Therefore, we computed a second regression plateau model to compare the expenditures for the GCreceived and the GC-assigned-but-not-received, and the UC group (Fig. 3). The GC-received group had lower expenditures than the UC group at baseline risk levels of 0.10-0.40. ITT is a standard method to evaluate methods from a randomized trial. We have provided both ITT and per protocol results to report a range of estimated magnitudes of cost differences. What we have observed in this study is that the GC-assigned-but-not-received group had the lowest expenditures at all risk levels and increases the magnitude of cost savings in the ITT analysis. Importantly, both figures show lower costs for all GC patients throughout lower baseline risk levels. DISCUSSION Administrative costs of providing the GC pilot can be estimated from the additional resources required during the 6-month period. These included salary and benefits for a full- time nurse, travel and other expense reimbursement, database development, laptop computer, printer, and office supplies. These costs totaled approximately $70,000. The dramatic increase in the number of older adults and the prevalence of chronic disease will contribute significantly to the future demand for health care resources and the rise in health care expenditures in the United States. More attention is being placed on the need to improve the quality of chronic care and the efficiency of health care expenditures for people with multiple chronic conditions. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is attempting to address these challenges by conducting several national demonstration projects.26 The results of this pilot study suggest that GC may reduce health care utilization and total insurance expenditures for high-risk older adults. Although the small sample size urges caution and reduces the precision of the estimated cost savings, the apparent trend toward lower insurance expenditures for persons receiving GC is encouraging and warrants further investigation. The observed higher savings at lower ACG-PM levels suggest the greatest differences may be attained among older people at less extreme levels of risk for health care GUIDED CARE OUTCOMES utilization. This relationship also warrants further study. This small pilot study has several significant limitations. The time period for evaluation was short, especially considering that aspects of the intervention require a change in health behaviors on the part of the patient in which the desired outcomes usually take longer than 6 months to realize. Of the 62 high-risk patients assigned to the GC group, 31 did not receive GC. Assignment to GC or UC was not random, and baseline differences that we were unable to measure, such as the propensity of GC-assigned patients to participate in the intervention, could have affected the outcomes we observed. In addition, unmeasured differences in the care provided by the GC and UC physicians could have affected the results. Further, the measurement of baseline characteristics and the identification of high-risk patients occurred several months before the study observation period began, so changes in patients’ status during this interval could have affected our results. Finally, we did not measure the costs of providing GC in detail. In summary, this pilot study suggests that GC, a nurse-led, patient-centered, primary-carebased, comprehensive approach to chronic care may reduce insurance expenditures for highrisk older adults. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial of the complete model of GC (including chronic disease self-management and caregiver education and support) is now addressing many of the limitations of this pilot study. This trial will provide more definitive information regarding the potential impact of GC on the quality and cost of health care for multimorbid older Americans. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Funding for the development and pilot-testing of Guided Care: Johns Hopkins HealthCare contributed the funding and administrative support for the guided care nurse, the development of the EHR, the analysis of claims data and supported Martha Sylvia’s time. Johns Hopkins Community Physicians contributed access to patients, the efforts of the PCPs, and office space and equipment at 35 the community-based primary care practice. The Lipitz Center for Integrated Health Care contributed seed funding, administrative support, and support for data analysis. Dr. Boyd was supported by the Johns Hopkins Bayview Scholars at the Center for Innovative Medicine at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. This abstract was presented in poster form at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, Seattle, WA, 2006; HMO Research Network Annual Conference, Portland, Oregon, 2007. REFERENCES 1. Weinstock M. Chronic care: an acute problem. Hosp Health Netw. 2004;78:40-48, 2. 2. Berenson RA, Horvath J. The clinical characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries and implications for Medicare reform. Paper presented at: Medicare Coordinated Care Conference; March 21–22, 2002; Washington, DC. 3. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Chronic Disease Overview. 2006. Available at: www. cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm. Last accessed on December 14, 2007. 4. Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162: 2269-2276. 5. Anderson G, Horvath J. Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Baltimore, MD: Partnership for Solutions; 2002. Available at: www.partnershipforsolutions.org/DMS/files/chronicbook2002.pdf. Last accessed on December 14, 2007. 6. Gruenberg L, Tompkins C, Porell F. The health status and utilization patterns of the elderly: implications for setting Medicare payments to HMOs. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 1989;10:41-73. 7. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. 8. McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635-2645. 9. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:64-78. 10. Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, et al. Guided care for multi-morbid older adults. The Gerontologist. In press. 11. Weiner JP, Abrams C, Bodycombe D. The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Version 6 Release Notes. Section 2. The ACG Predictive Model: Helping to Manage 36 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. SYLVIA ET AL. Persons at Risk for High Future Costs. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2003. Cumming RB, Knutson D, Cameron BA, Derrick B. A Comparative Analysis of Claims-based Methods of Health Risk Assessment for Commercial Populations. Minneapolis, MN: Society of Actuaries; Park Nicollet Institute Health Research Center; 2002. Dudley RA, Medlin CA, Hammann LB, et al. The best of both worlds? Potential of hybrid prospective/concurrent risk adjustment. Med Care. 2003;41:56-69. Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Meenan RT, Bachman DJ, O’Keeffe Rosetti MC. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care. 2003;41:84-99. Hu G, Root M. Accuracy of prediction models in the context of disease management. Dis Manag. 2005;8:4247. Juncosa S, Bolibar B, Roset M, Tomas R. Performance of an ambulatory casemix measurement system in primary care in Spain. European Journal of Public Health. 1999;9:27-35. Liu CF, Sales AE, Sharp ND, et al. Case-mix adjusting performance measures in a veteran population: pharmacy- and diagnosis-based approaches. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1319-1337. Perkins AJ, Kroenke K, Unutzer J, et al. Common comorbidity scales were similar in their ability to predict health care costs and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1040-1048. Pietz K, Ashton CM, McDonell M, Wray NP. Predicting healthcare costs in a population of veterans affairs beneficiaries using diagnosis-based risk ad- 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. justment and self-reported health status. Med Care. 2004;42:1027-1035. Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, Roos N, Atkinson M. Performance of the ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care. 2001;39:86-99. Wahls TL, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Predicting resource utilization in a Veterans Health Administration primary care population: comparison of methods based on diagnoses and medications. Med Care. 2004;42:123-128. Petersen LA, Pietz K, Woodard LD, Byrne M. Comparison of the predictive validity of diagnosis-based risk adjusters for clinical outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43: 61-67. Lachin JM. Statistical considerations in the intent-totreat principle. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:167-189. Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. Generalized Additive Models. News York: Chapman & Hall CRC; 1990. Hansen MH, Kooperberg C. Spline adaptation in extended linear models. Statistical Science. 2002;17:2-20. Wolff JL, Boult C. Moving beyond round pegs and square holes: restructuring Medicare to improve chronic care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:439-445. Address reprint requests to: Martha L. Sylvia, R.N., M.S.N., M.B.A. Johns Hopkins HealthCare 6704 Curtis Court Glen Burnie, MD 21060 E-mail: msylvia@jhhc.com