Sources and chemistry of secondary organic aerosols formed from

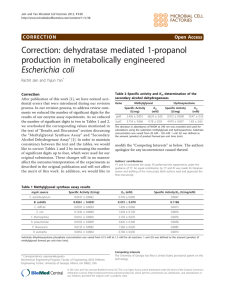

advertisement