Multimeter

Multimeter

Purpose of the Experiment

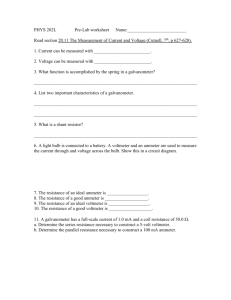

To understand the basic structures of a galvanometer, ammeter, and voltmeter, and familiarize students with the operation of a multimeter.

Experimental Principle

“Artisans must first sharpen their tools to perform well at work.” Several tools are required for exploring the world of electricity. A multimeter is one of these tools.

A multimeter, also known as a Volt-Ohm meter (VOM) or multitester, is an instrument that combines the functions of a galvanometer, ammeter, voltmeter, and ohmmeter. The functions provided by multimeters allow them to be employed in various fields. Before using any multimeter application, you must familiarize yourself with the basic device structure and functions, and before you can adeptly operate a multimeter, you must understand the principle of the device.

Based on the principle of the D’Arsonval galvanometer, the main function of a multimeter is measuring a circuit’s voltage, current, and resistance.

1. The Principle of a Galvanometer

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of a D’Arsonval galvanometer

Figure 2. Operational principle of a

D’Arsonval galvanometer

Fig. 1 is a schematic diagram of a D’Arsonval galvanometer with a permanent magnet and moving coil. Fig. 2 shows the operational principle of a D’Arsonval galvanometer. The moving coil, carrying a current I, produces a magnetic field that interacts with the magnetic field of the permanent magnet, thereby exerting clockwise torque L1 .The magnitude of the torque is directly proportional to I.

(1)

where k

1

is the proportionality constant. Torque L1 rotates the coil, and its relationship with torque L2, which is produced by spring torsion, attains equilibrium and can be expressed as

(2) where θ is the angular displacement of the coil, and k2 the spring’s torsion coefficient.

Equating Formulae (1) and (2), we obtain

Let ; therefore,

(3)

The current magnitude can be determined by the angle.

2. The Principle of an Ammeter

Fig. 3 shows a DC ammeter consisting of a galvanometer connected in parallel to a low-value resistor.

Figure 3.

Ig: current passing through the galvanometer

Is: current passing through Rs and

Rg: internal resistance of the galvanometer

I: input current

(4)

(5)

Modifying Rs determines the measurement range of the ammeter.

3. The Principle of a Voltmeter

Fig. 4 shows a DC voltmeter consisting of a galvanometer connected in series to a high-value resistor.

Let Vg be the highest voltage measured by the galvanometer, and V be the highest voltage to be measured.

(6)

Figure 4.

(7)

(8)

4. The Principle of an Ohmmeter

Figure 5.

Fig. 5 shows an ohmmeter comprising a galvanometer, resistors, and a power source. High Rx (e.g., air) leads to a small current that barely moves the indicator. For a small Rx (e.g., short circuit), R l

can be adjusted to maximize the indicator reading. According to Ohm’s law,

(9) and

(10)

Thus, we have

(11) therefore,

(12) where Rx is the test resistor, and Ig is the current passing through the galvanometer. The scale is nonlinear because, according to Formula (12), the relationship between Ig and Rx is nonlinear.

Laboratory Instruments

Breadboard, analog multimeter, digital multimeter, power supply, resistors

Notes

1. For resistance measurements, do not apply external power because it may damage the multimeter.

2. Choose the appropriate measurement range or position, and start from the range or position with the highest multiple.

3. To avoid damaging digital multimeters, first use an analog multimeter to measure currents. Digital multimeters can only be used for current measurement after the assistant confirms that the multimeter is properly connected in series to the circuit.

4. After measurement using the analog multimeter, ensure the measurement range is switched to OFF instead of a resistance range.

Experimental Procedure

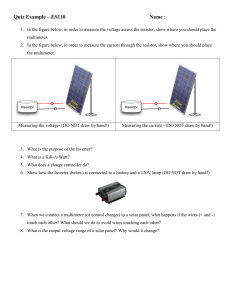

A. Analog Multimeter

1. Consult the appendix and record the resistance readings of 5 resistors.

2. Calibrate the analog multimeter. a. Zero calibration: move the zero position adjuster to align the indicator with the line on the far left. b. Range or position selector: select the appropriate measurement ranges or positions based on the circumstances, and switch to OFF after measurement. c. Connection of test leads: connect the red and black test leads to the (+) and (-) terminals, respectively.

3. Use the multimeter to measure the resistance value. (Note: Perform the zero calibration procedure before every resistance measurement.)

4. Compare the resistance values obtained from Steps 1 and 3.

5. Use the multimeter to determine whether a short circuit or an open circuit occur in the breadboard.

Complete the circuit distribution on the breadboard.

6. Install the resistors used in Step 1 on the breadboard following the circuit shown in Fig. (6).

Figure 6.

7. Use the multimeter to measure the values of R

AC

, R

BD

, R

CD

, and R

AD

, and verify whether the measured values correspond to the results of the series and parallel circuit formulae.

8. Connect terminals A and D to the positive and negative terminals of the power supply, respectively.

9. Use the multimeter to measure V

AB

, V

BC

, V

CE

, V

ED

, V

CD

, and V

AD

.

10. Interpret the values obtained from Step 9.

11. Use the multimeter to measure the current passing through .

12. Verify Ohm’s law using the results obtained from Steps 7, 9, 10.

13. Measurement of AC voltages

a. Select an appropriate ACV position (1000 V).

b. Insert the test leads into the electrical sockets on the experiment table. Record the

AC voltage readings.

B. Digital Multimeter

Repeat Steps A3 to A13 using a digital multimeter.

Questions for Reflection

1. Connect the test leads to reversed terminals. How does the measurement of voltage and current differ?

2. What types of measurement can the analog multimeter perform without batteries?

3. Consider an unknown resistor R ( ), and attempt to solve the following questions using a voltmeter ( ), ammeter ( ), and a voltage source ( ): a. Draw two circuits that use both a voltmeter and ammeter to measure R. b. Discuss or infer the difference or error between the R measurements of the two circuits. c. If R is a low-value resistor, which of the two circuits in 3a can provide a more accurate measurement? Explain why.

4. Why is the measured voltage a constant when a multimeter is used to measure the AC voltage from the socket, which should be a sine wave at a frequency of 60 Hz.

5. Assume you only have access to a DC ammeter with a full-scale reading of 100 mA, how would you measure a DC voltage of 1000 V using the ammeter and several additional resistors?

Appendix

A. Resistor value color codes

Color codes denote numbers for resistors. These codes are defined below.

Color 1 st

band 2 nd

band 3 rd

band 4 th

band

Black

Brown

1 st

digit 2 nd

digit Multiplier

0 0

100

1 1

101

Red 2 2

102

Orange 3 3

103

Yellow 4 4

104

Green 5 5

105

Blue 6 6

106

Violet 7 7

107

Gray 8 8

108

White 9 9

109

Gold -- --

10-1

Silver -- --

10-2

--

1%

2%

--

--

--

--

--

--

Tolerance

0.5%

5%

10%

※

None -- -- -- 20%

※ Used on specific occasions

【 Example 1 】 Determine the resistance value of the resistor shown in Fig.

(1).

Figure (1).

R = (24×101) (Ohms) = 240 (Ohms) +/-10%

【 Example 2 】

R = (909×102) (Ohms) = 9.09×104 (Ohms) +/-1%

Figure (2).

B. Surface-mount resister readings:

102 => 10×102=100( Ω )