The Laws, Regulations, and Industry Practices That Protect

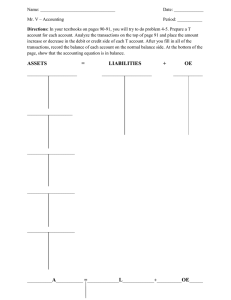

advertisement