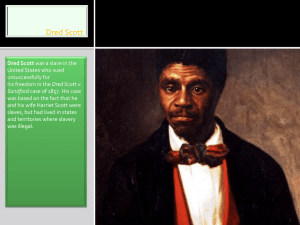

What Was Wrong with Dred Scott, What`s Right about Brown

advertisement