Evidence Based Practice for Information Professionals: A

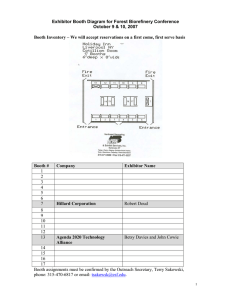

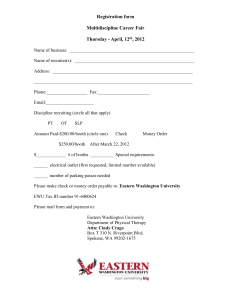

advertisement