Assessment and feedback policy

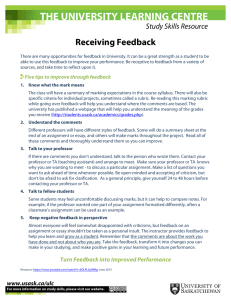

advertisement