Information Security Policy - A Development Guide for Large

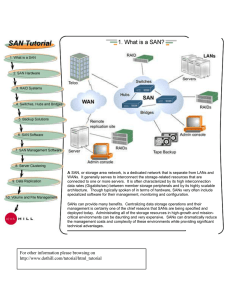

advertisement