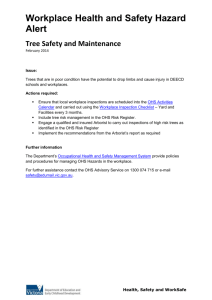

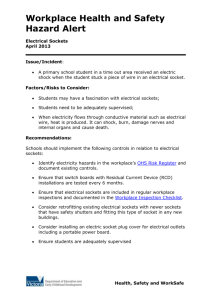

working safely in community services

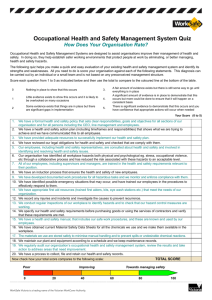

advertisement