Multi-Dimensional Information-based Online Museum for History

advertisement

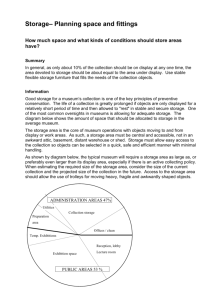

International Journal of Cyber Society and Education Pages 1-22, Vol. 5, No. 1, June 2012 Multi-Dimensional Information-based Online Museum for History Beginners Bin-Yue Cui Nagoya University/Hebei University of Economics and Business Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, 464-8601, Japan/ No. 47, XueFu Road, Shijiazhuang City, Hebei, China binyuecui@nagoya-u.jp Shige-Ki Yokoi Nagoya University Furo-chou, Cikusa-ku, Nagoya 464, Japan yokoi@is.nagoya-u.ac.jp ABSTRACT The Internet has spurred the popularity of online or virtual museums that preserve historical heritages and promote traditional cultures. However, the contents of existing online museums are often too professional for ordinary visitors to understand. This situation dampens visitor interest toward historical cultures or heritages, especially such history beginners who often lack sufficient background knowledge. In this paper, we designed and developed a prototype system for online museums for beginners based on an investigation of existing online museums and the cognitivism of learning and social constructivism theories. Our proposed system has several points that are different from existing online museums: (1) it illustrates artworks with multidimensional information; (2) it integrates correlative information around artworks; (3) it locates artworks on Google Maps based on their geographic information. Our online museum offers great help for history beginners and will facilitate a deeper understanding of history. Keywords: Online Museum, History Beginner, Investigation, Cognitivism, Constructivism, Correlative Information, Multi-dimension Information, Google Maps International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 2 INTRODUCTION Modern technology in its various forms has pervasively permeated the existing environments of museums. “Museums are interested in the digitizing of their collections not only for the sake of preserving the cultural heritage, but to also make the information content accessible to the wider public in a manner that is attractive” (Sylaiou et al., 2009). Virtual or online museums have been accepted widely and play an essential role in popularizing historical knowledge and preserving historical heritages. There are different definitions of online museums. The “virtual museum” establishes access, context, and outreach using information technology (Werner, 1998). An online museum or virtual museum is a “collection of digitally recorded images, sound files, text documents, and other data of historical, scientific, or cultural interest that are accessed through electronic media” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010). It is usually a collection illustrated by images, sound files, text documents, and other data of historical, scientific, or cultural interest that are accessed through electronic media. “A virtual museum … takes advantages of new media digital innovative implementations to display, preserve, reconstruct, disseminate, and store collections” (Euro INNOVANET, 2008). Other names for a virtual museum include online museum, electronic museum, hyper museum, digital museum, cyber museum, or web museum, depending on the backgrounds of the practitioners and researchers (Werner, 2004). In our research (Cui & Yokoi, 2010), we designed and developed an online museum for history beginners. Much recent research exists about educating students or the public by online museums (Okolo et al., 2007; Rayward & Twidale, 1999; Robert A. et al., 2005) that emphasizes on online education by new technologies. To some extent, these researches are education-oriented methods for every online user to popularize history knowledge. In our research, we built an online museum for history beginners and provided background knowledge of collections in local museums by multi-dimensional information that is both inside and outside of local museums. In this paper, an online museum for history beginners is defined as a collection of digitalized information resources, such as images, textual documents, 3D models, flash documents, videos, and audio files of relics collected in physical museums. Additionally, correlative multi-dimension information is included from other institutes online for people with little history background or knowledge. The result raises the interest of beginners in collections and historical heritages or cultures. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 3 In recent years, the term “virtual museum” has been evoked so often that a Google search in June, 2009 garnered more than 1.1 million hits. In many cases, “Virtual visitors to museum websites already out-number physical (on-site) visitors, and many of these are engaged in dedicated learning” (Kravchyna & Hastings, 2002). Museums have a crucial role in facilitating life-long learning (Roy, 2004). Virtual or online museums are not only in vogue, but they reflect the increasing demand of online learning. The majority of online visitors are young people or history beginners who are usually competent with computer operation or network technologies. However, professional introductions with complicated terms are often difficult for them to understand. Therefore, history beginners must be enticed to have interest in history or traditional culture as well as encouraged to learn more about history or cultures by online museums (Cui et al., 2009). In this paper, we investigated 30 existing online museums and designed an online museum for history beginners, the Tokugawa Art Museum project, which addressed the necessity of providing correlative information of collections when an item is introduced online. This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we surveyed existing online museums from the perspective of history beginners and indicated some current issues faced by them. In Section 3, we designed an online museum based on our survey and the cognitivism of learning theory and social constructivism theory. Finally, we drew our conclusions, discussed the limitation of our system, and described the future tasks. SAMPLING SURVEY OF EXISTING ONLINE MUSEUMS FROM PERSPECTIVE OF HISTORY BEGINNERS As a popular way to conduct universal education, online museums provide significant knowledge about collections, history, local cultures, and so on. However, the question remains: is the presentation of collections suitable for history beginners? We sampled existing online museums. Table 1 Distribution of Samples (Jun. 2009) Number of Online Museums Europe 8 Asia 9 America 8 Australia 4 Africa 1 Total 30 International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 4 Analysis of Sampling Survey The sought the usual way to present collections in virtual museums, and whether that method is easily accessible for history beginners or young people with little history information or knowledge. We searched online museums by Google and selected 30 samples by locations. To assure that the samples represent the population well, we randomly selected them from different continents online. The distribution of the stochastic selected samples is shown in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, in Asia, we selected nine samples, including the Palace Museum, the Tokyo National Museum, the Tokugawa Art Museum, and so on. Eight samples were selected from both Europe and America. In Africa, the Egypt Museum is very famous because of its vast rare collections of ancient Egyptian artifacts. Consequently, it was chosen as a sample in our survey. Four online museums of Australia were investigated. This survey, which consisted of three main sections designed to evaluate the usual ways of presenting collections in existing virtual museums, analyzed whether designing an online museum for history or young people is suitable to deepen their understanding of history or culture. This sampling survey focused on three sections: basic information of collections correlative information of collections source of data: inside or outside First, we investigated the basic information of the collections of existing online museums. Table 2 shows data relating to how the selected virtual museums provided online users with the basic information of their respective collections and what content was available to the public on these web pages. Table 2 Basic Information of Collections in Online Museums (Jun. 2009) Items Picture and Description 3D Models Flash Interactive /Animation Video or Audio Geographic Info on Map Europe Asia America Australia Africa Total (%) 8 9 8 4 1 30 100.00 3 2 0 0 1 6 20.00 1 3 1 1 0 6 20.00 3 3 1 3 0 10 33.33 0 1 2 0 0 3 10.00 International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 5 Table 2 indicates that the most popular way to present collections is by pictures with relevant descriptions. In our survey, all the sampled online museums introduced their collections in this way. Furthermore, services like YouTube, Twitter, Digg, Myspace, and Mixx were used in some virtual museums. Users tend to share thoughts and reactions about interesting collections with other online social communities. In addition, 3D technologies, Virtual Reality, and Flash are commonly used in virtual museums today. 20% of the samples presented 3D virtual tours, 3D models, or Flash animation of collections online, allowing users to see details of the collections, such as the bottom, top, or interior of each antique. Relevant video was sometimes directly linked to YouTube. 33.3% of the samples, including those from the British Museum and Field Museum, had video and audio services to introduce each collection. All the methods will greatly help history beginners achieve a better understanding of history or cultures. About 10% of the sample virtual museums used maps to show the geographic information of their collections. The Metropolitan Art Museum of New York, for instance, displayed the distribution of art works in terms of their location based on a map entitled “Timeline of Art History” (Figure1). Another example is the American Museum of Natural History, whose website featured digitally imaged objects from Africa, Europe, and Asia. Users can access an introduction to any collection in certain areas by clicking the corresponding icons (Figure 2). Displaying information on a map is a direct way for online visitors, especially beginners, to find something of interest, or help them understand the locations of collections. However, the maps used in sample virtual museums are all pictures of maps that cannot be zoomed in or out. Additionally, the icons on the maps just represent the geographic categories of collections, not the collections themselves. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 6 Note: from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/world-regions/#/06/World-Map Figure 1 Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art Note: from http://anthro.amnh.org/anthro_coll.shtml Figure 2 Map taken from American Museum of Natural History Second, we investigated whether there is correlative information about collections to facilitate the understanding of history or traditional cultures for history beginners. 70% of the sampled online museums did not give correlative information. Compared with noncorrelative information, nine online museums provided correlative information about International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 7 related cultures, persons, events, and objects that could provoke the interest of history beginners. However, the correlative information is insufficient, since it is always limited to a local database (Table 3). Although almost all correlative information came from a local database, it not only supplements the basic information but also functions as the main point to encourage history beginners to understanding the collections or historical heritages. Table 3 Correlative Information of Collections in Online Museums (Jun. 2009) Items Correlative No Info Yes Yes Related Cultures Related Persons Related Events Related Objects Academic Papers Europe 7 1 1 0 0 0 0 Asia 7 2 1 0 0 1 1 America 3 5 1 1 1 1 3 Australia 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 Africa 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 Total 21 9 3 2 1 3 4 (%) 70.00 30.00 10.00 6.67 3.33 10.00 13.33 Finally, 90% of the online museums failed to provide access to the databases of other institutes or cites with related content from other partner online museums or web pages. Table 4 indicates that merely 10% acquired data from outside databases of cooperating partners. 90% of online museums remain self-sufficient, because their presented collections mainly depend on data from local databases. Table 4 Data from Outside Museums(Jun. 2009) Items Europe 6 Data from outsides No sources Yes 2 Asia 9 0 America Australia Africa 7 4 1 1 0 0 Total 27 3 (%) 90.00 10.00 Current Issues In our sampling survey, we found the following problems for beginners or people with little historical knowledge when they visit existing virtual museums. (1) Illustrated artworks with 2-dimensional information. We found that 100% of samples used a picture and a brief introduction (2-dimension) to present their online artworks. History beginners with little background in historic events, periods, or persons will probably be disappointed by 2-dimensional information because it fails to cater to International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 8 their needs. Multi-dimensional information as correlative information around online artworks is necessary to help beginners understand history or traditional culture. (2) Only 30% of existing online museums provided correlative information about collections, mainly restricted to a small amount of knowledge prepared in advance from a local database. In fact, beginners need much more information. 70% of sampled museums presented online collections in usual way. (3) Virtual museums paid little attention to the geographic information of collections. Online collections are generally introduced as pictures or 3D models with descriptions. History and geography beginners and novices are probably unaware where a collection was found or where it had been previously without the geographic information shown on maps. SYSTEM DESIGN OF ONLINE MUSEUM FOR HISTORY BEGINNERS Based on the above sampling survey, a significant amount of existing online museums is obviously not considering the need of history beginners. For such people, online museums should be designed and built that encourage their interest in local traditional cultures or historical knowledge to protect the world’s historical heritages. We designed an online museum based on the research findings of cognitivism of learning theory and social constructivism theory. “Learning theory is an attempt to describe how people and animals learn, thereby helping us understand the inherently complex process of learning” (Wikipedia, 2010). This theory is underscored by three frameworks: behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. Cognitivism, which indicates a learning process from the perspective of psychology, emphasizes that prior knowledge plays an important role in the learning process. Jeremy (1997) states that “A large body of findings shows that learning proceeds primarily from prior knowledge, and only secondarily from the presented materials.” Prior knowledge will help users understand new knowledge. Background knowledge will also benefit learners to learn and utilize new knowledge, according to social constructivism theory. Social constructivism considers each learner a “unique individual with unique needs and backgrounds.” Learner is also are seen as “complex and multidimensional” (K12 Academic, 2010). From the perspective of social constructivism, social interaction is crucial for learners to acquire social meaning and to use it in practice by building background knowledge from social interaction with others with related knowledge. Wertsch (1997) states that during the International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 9 learning process, the background knowledge and culture of learns shapes the knowledge and truth that a learner creates, discovers, and attains in the process of learning. Regardless of prior knowledge or background knowledge, both terms are described in the same conceptual frameworks (Strangman & Hall, 2004). Stevens (1980) defined background knowledge as “what one already knows about a subject” (p.151). Some researchers define prior knowledge as the entirety of an individual’s knowledge, including explicit and tacit knowledge (Dochy & Alexander, 1995). Nicole Strangman and Tracey Hall (2004) investigated many research references and concluded that prior knowledge and background knowledge are quite similar and can be used interchangeably. Based on the above theory, the primary task for developing a online museum for history beginners is retrieving and integrating correlative information about one collection and building the background knowledge of collections to facilitate online learning of history by beginners. On one hand, providing users with correlative information about one collection builds the background knowledge of collections, addressing the situation in which users cannot interact in online museums, which they can do in actual museums. On the other hand, background knowledge is composed of the correlative information of one collection, such as related historical events, persons or even craftsmanship. The more correlative information provided, the higher is the probability that users can discover knowledge related to their prior knowledge. Therefore, online museum for history beginners provide multi-dimensional information as background knowledge to support online learning. Solutions to Current Issues According to some current issues found in our sampling survey, we ascertained the following solutions (Table 5). In ordinary online museums, maps are seldom used to show visitors the geographic information of antiques; only 10% of the samplings used maps to show the sources of their collections. However, maps remain inadequate because they cannot be zoomed in or out. In our system, some collections in the Tokugawa Art Museum were located on Google Maps to allow history beginners to develop a clear idea about the geographic information of items. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 10 Table 5 Solutions to Current Issues of Online Museums Current Issues 2-Dimensional information: Images Brief introduction Deficiency of correlative information Data sources mostly limited to local databases. Textual Geographic information The samples museum online seldom expressed geographic info of collections by maps. Solutions Multi-dimensional information: Build ontology model to illustrate connections among correlative information and make it available to illustrate collections by multidimensional information. Application of Online Archives: Search for multi-dimension information from both local DB and online archives. Google Maps based geographic info Visualize geographic information of collections by locating them on Google Maps. History beginners have difficulty finding correlative information in the majority of investigated online museums. In our system, correlative information is provided. Concerning data sources, obviously, local databases can hardly provide all the correlative information for online museums visited by history beginners. Thus, an outside data source is required, such as information from the web pages of other websites. Architecture of Online Museum for History Beginners Based on the above analysis, a beginner-oriented online museum is illustrated in Figure 3. Compared with usual online museums, this system offers the following new points. First, it gives history beginners correlative information from both inside and outside the local museum. Second, Google Maps is used to display the distribution of museum collections. Third, a route map of certain antiques shows users their journeys before being assed to the museum. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 11 Figure 3 Architecture of Online Museum for History Beginners There are two kinds of data sources in our system. One is a local database (part 2 of Figure 3); the other is information distributed on networks (part 1 of Figure 3). In our system, an outside resource was used by keyword retrieval by a Google search engine. Fully exploring outside resources is another of the system’s characteristics. Logical relationships can be simply illustrated in Figure 4. Figure 4 Illustration of System Data Source International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 12 In addition, history or culture experts contribute intangible knowledge to history beginners online. They can even upload materials about one online antique or give comments and further information about it as supplementary knowledge. Multi-Dimensional Information in Online Museum for History Beginners In a survey call the Information Value of Museum Website, (Kravchyna & Hastings, 2002), 63% of the interviewed on-line users, including scholars, teachers, and students, looked for information about collections. 49% needed information about images, and 48% needed information for research. Thus, integrating different kinds of knowledge spread across many institutes would give the final users a unique and rich experience. For history beginners, such encompassing knowledge will provoke their interest in history and traditional cultures. Note: from http://www.tokugawa-art-museum.jp/artifact/room3/04.html Figure 5 Illustration of Collections in Website of Tokugawa Art Museum International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 13 Note: from http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/s/stone_lions_head.aspx Figure 6 Illustration of Collections in Website of British Museum When history beginners enjoy a collection online through an online museum’s interface, they can usually see pictures and relevant introductions (Figure 5 and Figure 6). One system, which was developed to build virtual museums also builds online illustrations of collections with pictures and descriptions (Amigoni & Schiaffonati, 2009) For example, a bowl was made in the Momoyama period. However, since beginners probably know little about this historical period, they might want more details about it. What was famous in that period? Who made that bowl? Do similar bowls exist? What materials was it made of? Yet, no such correlative information is provided on usual museum web sites. Thus, an illustrated collection with pictures and brief introductions is inadequate for history beginners. In this online museum, collections are introduced by multi-dimensional information (Figure 7). In addition to the picture and the introduction, the following correlative information is included antiques, persons, history events, time periods, geographic information, and even fabrication. Introducing a collection online by multi-dimensional information facilitates the understanding of history. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 14 Figure 7 Multi-Dimensional Information History beginners can easily access the correlative information about one collection from both internal and external databases. Related Collections In our system, collections will be connected by shared keywords (Figure 8). If one antique is visited, users can easily visit other antiques that share identical keywords. Take antique 1 for instance. Users can get information about antiques 2 and 3 by selecting keyword 4 of antique 1. Based on keyword 4, antiques 4 and 5 can be also visited through antique 3. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 15 Figure 8 Keyword based Relationship among Collections (Principle) The process is illustrated by Figure 9 below. Figure 9 Keyword based Relationship among Collections (User Interface) In addition to connections among collections, relationships between collections and history knowledge will also be provided to history beginners online in the next step of our research. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 16 Collections in the Tokugawa Art Museum will be distributed on a timeline. With this timeline, users can easily find knowledge about historical periods, events, and characters. Related Persons In our system, the related persons around one collection are also available for history beginners who can obtain more knowledge about the interpersonal relationships between collections. Two parts of the data sources can be shown on our online museum’s user interface. Some basic interpersonal relationship information is saved in a local database. We also obtained some information from other web pages and showed it on our user interface (Figure 10). The key historical events around one historical character can also be found in our online museum. All of these will obviously arouse history beginners’ interest and facilitate finding more correlative knowledge online. Figure 10 Information of Related Persons Visualizing Geographic Information of Collections based on Google Maps In our sampling survey, maps were used in several online museums. However, they couldn’t be zoomed in or out or load more information except for icons, by which to display a collection or a category of collections. In our system, a “Collection Map” was International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 17 made that directly visualized the geographic information of collections. Beginners can more conveniently find where the collections come from with collection maps than by reading textual geographic information on web pages. In 2008, Google launched its Google Maps Application Programming Interface (API) and allowed users to embed Google Maps in any website with JavaScript. After Google Maps was launched, its users increased dramatically and many professional systems were developed for it (Yao-Jan Wu, 2007). The search engine ranking of key words retrieved in 2008 showed that “map” rose from 19th to 13th (Takebe, 2009). In this system, the basic description and collection images were uploaded on geographic information from Google Maps. Referring to the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) proposed by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) (ICOM/CIDOC Documentation Standards group, 2009), we defined the data dictionary of collections. In this online museum, geographic information is divided into three kinds: (1) Product location: Where was the antique made? We built a collection map for users based on such geographic information by navigation of a time bar. Key history events are also illustrated on this web page. Integrated information dissolves many problems for history beginners when searching for correlative information online (Figure 11). Figure 11 Collection Map in our Prototype System International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 18 (2) Preserving location inside the museum. Dynamic locations are changed in terms of different exhibitions in the museum. With such information, an exhibition map shows inside the museum is made. (3) Previously visited locations N (1, 2, 3 …N, N>=1). Where else has the collection been? Collections normally travelled to many places before preserved by a museum. Figure 12 Process Diagram of Drawing the Route Map of Collections Therefore, the previous locations of one collection should be recognized and saved in a database. A route map of certain collections will be developed using such geographic information from the collection. In many cases, when visitors are roaming classical or online museums, they are curious about who previously owned the artifact. Where else has the antique been? However, such information is rarely supplied in both kinds of museums. Compared with the usual cases, users will learn where certain collections have been by route maps of the collections in this online museum. As shown in Figure 12, the preservation place, the previously visited places, and the production place of a certain artifact are marked on Google Maps and connected by orange lines. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORKS In this paper, based on a sampling survey of existing museum websites, we identified some problems experienced while history beginners are visiting general online museums. First, collections illustrations are mainly limited to 2-dimension informationpictures and text introductions because the collection cannot be fully presented online. Second, only a small amount of the correlative information of collections is available International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 19 online, hindering by users. Finally, geographic information is described by text in most cases, which cannot directly express geographic information. Based on the current issues, we provided relevant solutions and proposed a system design of an online museum for history beginners. A prototype system was also correspondingly developed. In this online museum for history beginners, we did the following: (1) Presented particular artworks by substituting multi-dimension information for 2-dimension information. (2) Integrated correlative information around certain artworks to facilitate history beginners’ understanding of history heritages and cultures. (3) Visualized the different geographic information of antiques on Google Maps. All of these will greatly help history beginners gain better understanding of history and arouse their interest in historical heritages when they are roaming in exploring this online museum. However, some limitations must also be solved in our museum system in subsequent research. For instance, the data from local databases does not cater to the needs of presenting collections with multi-dimension information. Therefore, we must retrieve related information or online archives by determining how to analyze related web pages to verify the needed information and organize the related multi-dimension information around one collection. In addition, social media are becoming a popular way to generate and transfer social knowledge. All kinds of information from professionals or laypersons around a certain topic can be gathered. Knowledge from social media will also function as a supplementary data source for online museums to encourage users to further study online with those who share interests. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank the Tokugawa Art Museum who provided materials of rare antiques and valuable suggestions. REFERENCES Amigoni, F., & Schiaffonati, V. (2009). The Minerva system: A step toward automatically created virtual museums. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 23(3), 204232. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 20 Binyue Cui, & Shige-ki Yokoi. (2010). Correlative information-based online museum for history beginners. Paper presented at 2010 e-Case & e-Tech International Conference, Macau, China. Binyue Cui, Shigeki Yokoi, & Jien Kato. (2009). Integrating correlative knowledge in virtual museum with Google Maps. Paper presented at the Conference of the Japan Society for Socio-Information Studies, Japan. Dochy, F.J. R.C. & Alexander, P.A. (1995). Mapping prior knowledge: a framework for discussion among researchers. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 10(3), 225-242. Euro INNOVANET (Roma). (2008). Building a new concept of virtual museum four case-studies on best practices, Report of F-MU.S.EU.M. Project. ICOM/CIDOC Documentation Standards Group. (2009). Definition of the CIDOC conceptual reference model, continued by the CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. In K12 Academic. (2010). Constructivist learning intervention. Retrieved November 10, 2010, from http://www.k12academics.com/educationreform/constructivism/constructivist-theory/constructivist-learning-intervention Jeremy, R. (1997). Learning in Interactive Environments: Prior Knowledge and New Experience. Retrieved November 30, 2010, from http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/museumeducation/priorknowledge.html Kenichi Takebe. (2009). Improving the accuracy and representability of new technology. NIKKEI communications, 526, 22-29. Kravchyna, V. & Hastings, S. (2002). Informational value of museum. Retrieved September 12, 2009, from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/929/851 Okolo, Cynthia M., Englert, Carol Sue, Bouck, Emily C., Heutsche, & Anne M. (2007). Web-based history learning environments: Helping all students learn and like history. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(1), 3-11. Rayward, W. B., & Twidale, M. B. (1999). From docent to cyberdocent: Education and guidance in the virtual museum. Archives and Museum Informatics, 13(1), 23-53. Robert A, C. & Ward Mitchell, C. (2005). Survey of web-based educational resources in selected U.S. art museums. Retrieved September 12, 2009, from http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_2/kravchyna/index.html Roy, H. (2004). Learning with digital technologies in museums, science centers and galleries. London: Future Lab Series Report 9. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 21 Stevens, K.C. (1980). The effect of background knowledge on the reading comprehension of ninth graders. Journal of Reading Behavior, 12(2), 151-154. Strangman, N., & Hall, T. (2004). Background knowledge. Retrieved November 11, 2009, from http://www.aim.cast.org/learn/historyarchive/backgroundpapers/background_knowl edge Sylaiou, S., Liarokapis, F., Kotsakis, K., & Patias, P. (2009). Virtual museums, a survey and some issues for consideration, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 10(4), 520-528. Virtual Museum. (2009). In Wikipedia. Retrieved July 16, 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_museum Virtual Museum. (2010). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 28, 2010, from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/630177/virtual-museum Werner, S. (1998). The “Virtual Museum”: New perspectives for museums to present objects and information using the Internet as a knowledge base and communication system. Paper presented at the 6th International Symposium on Information Science (ISI 1998), Prague. Werner, S. (2004). Virtual museums: The development of virtual museums. Retrieved February 20, 2010, from http://icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/ICOM_News/20043/ENG/p3_2004-3.pdf Wertsch, J. V. (1997). Sociocultural Studies of Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wikipedia. (2010). Learning theories. Retrieved November 3, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_theory_(education) Yao-Jan Wu. (2007). Google Maps based arterial traffic information system, Intelligent Transportation System Conference. Paper presented at the 2007 IEEE, WA, USA. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education 22