Orange County Cusp of Change - Orange County`s Healthier Together

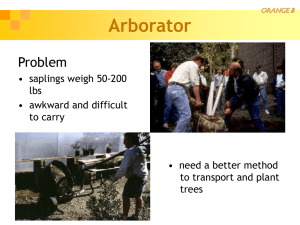

advertisement