Free Trade, Public Goods and Regime Theory : A theoretical

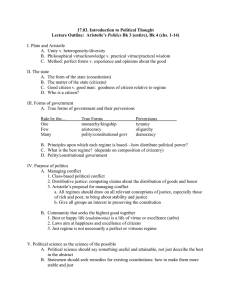

advertisement