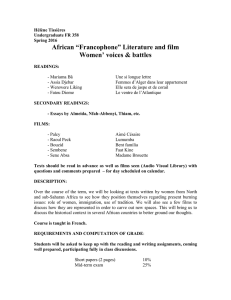

fulltext

advertisement