Part Two LOCAL CONTEXT AND INTERNATIONAL

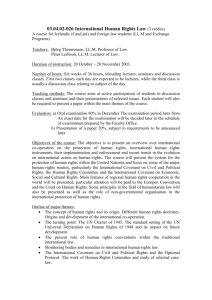

advertisement