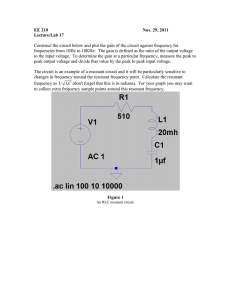

19: Resonant Conversion

advertisement

Chapter 19

Resonant Conversion

Introduction

19.1

Sinusoidal analysis of resonant converters

19.2

Examples

Series resonant converter

Parallel resonant converter

19.3

Exact characteristics of the series and parallel resonant

converters

19.4

Soft switching

Zero current switching

Zero voltage switching

The zero voltage transition converter

19.5

Load-dependent properties of resonant converters

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

1

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Introduction to Resonant Conversion

Resonant power converters contain resonant L-C networks whose

voltage and current waveforms vary sinusoidally during one or more

subintervals of each switching period. These sinusoidal variations are

large in magnitude, and the small ripple approximation does not apply.

Some types of resonant converters:

• Dc-to-high-frequency-ac inverters

• Resonant dc-dc converters

• Resonant inverters or rectifiers producing line-frequency ac

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

2

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

A basic class of resonant inverters

NS

NT

is(t)

Basic circuit

+

dc

source

vg(t)

+

–

vs(t)

i(t)

L

Cs

+

Cp

v(t)

–

–

Switch network

Resistive

load

R

Resonant tank network

Several resonant tank networks

L

Cs

L

L

Cp

Series tank network

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Parallel tank network

3

Cs

Cp

LCC tank network

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Tank network responds only to fundamental

component of switched waveforms

Switch

output

voltage

spectrum

fs

3fs

5fs

f

Resonant

tank

response

fs

3fs

5fs

f

fs

3fs

5fs

f

Tank current and output

voltage are essentially

sinusoids at the switching

frequency fs.

Output can be controlled

by variation of switching

frequency, closer to or

away from the tank

resonant frequency

Tank

current

spectrum

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

4

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Derivation of a resonant dc-dc converter

Rectify and filter the output of a dc-high-frequency-ac inverter

Transfer function

H(s)

is(t)

+

+

dc

source +

–

vg(t)

L

Cs

+

vR(t)

vs(t)

v(t)

R

–

–

NS

Switch network

i(t)

iR(t)

–

NT

Resonant tank network

NR

NF

Rectifier network Low-pass dc

filter

load

network

The series resonant dc-dc converter

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

5

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

A series resonant link inverter

Same as dc-dc series resonant converter, except output rectifiers are

replaced with four-quadrant switches:

i(t)

+

L

Cs

dc

source +

–

vg(t)

v(t)

R

–

Switch network

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Resonant tank network

6

Switch network

Low-pass ac

filter

load

network

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Quasi-resonant converters

In a conventional PWM

converter, replace the

PWM switch network

with a switch network

containing resonant

elements.

Buck converter example

i1(t)

+

vg(t) +

–

v1(t)

Two

switch

networks:

+

Switch

network

C

v2(t)

R

v(t)

–

–

ZCS quasi-resonant

switch network

PWM switch network

i2(t)

i1(t)

+

+

+

v1(t)

v2(t)

v1(t)

–

–

–

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

i(t)

+

–

i1(t)

L

i2(t)

7

Lr

Cr

i2(t)

+

v2(t)

–

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Resonant conversion: advantages

The chief advantage of resonant converters: reduced switching loss

Zero-current switching

Zero-voltage switching

Turn-on or turn-off transitions of semiconductor devices can occur at

zero crossings of tank voltage or current waveforms, thereby reducing

or eliminating some of the switching loss mechanisms. Hence

resonant converters can operate at higher switching frequencies than

comparable PWM converters

Zero-voltage switching also reduces converter-generated EMI

Zero-current switching can be used to commutate SCRs

In specialized applications, resonant networks may be unavoidable

High voltage converters: significant transformer leakage

inductance and winding capacitance leads to resonant network

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

8

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Resonant conversion: disadvantages

Can optimize performance at one operating point, but not with wide

range of input voltage and load power variations

Significant currents may circulate through the tank elements, even

when the load is disconnected, leading to poor efficiency at light load

Quasi-sinusoidal waveforms exhibit higher peak values than

equivalent rectangular waveforms

These considerations lead to increased conduction losses, which can

offset the reduction in switching loss

Resonant converters are usually controlled by variation of switching

frequency. In some schemes, the range of switching frequencies can

be very large

Complexity of analysis

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

9

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Resonant conversion: Outline of discussion

• Simple steady-state analysis via sinusoidal approximation

• Simple and exact results for the series and parallel resonant

converters

• Mechanisms of soft switching

• Circulating currents, and the dependence (or lack thereof) of

conduction loss on load power

• Quasi-resonant converter topologies

• Steady-state analysis of quasi-resonant converters

• Ac modeling of quasi-resonant converters via averaged switch

modeling

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

10

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.1 Sinusoidal analysis of resonant converters

A resonant dc-dc converter:

Transfer function

H(s)

is(t)

+

+

dc

source +

–

vg(t)

L

Cs

+

vR(t)

vs(t)

v(t)

R

–

–

NS

Switch network

i(t)

iR(t)

–

NT

Resonant tank network

NR

NF

Rectifier network Low-pass dc

filter

load

network

If tank responds primarily to fundamental component of switch

network output voltage waveform, then harmonics can be neglected.

Let us model all ac waveforms by their fundamental components.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

11

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

The sinusoidal approximation

Switch

output

voltage

spectrum

fs

3fs

5fs

f

Resonant

tank

response

fs

3fs

5fs

f

Tank

current

spectrum

Tank current and output

voltage are essentially

sinusoids at the switching

frequency fs.

Neglect harmonics of

switch output voltage

waveform, and model only

the fundamental

component.

Remaining ac waveforms

can be found via phasor

analysis.

fs

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

3fs

5fs

12

f

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.1.1 Controlled switch network model

4

π Vg

NS

Vg

is(t)

1

vg

+

–

Fundamental component

vs1(t)

vs(t)

+

t

2

2

vs(t)

–

1

– Vg

Switch network

If the switch network produces a

square wave, then its output

voltage has the following Fourier

series:

4Vg

vs(t) = π

Σ 1n sin (nωst)

The fundamental component is

4Vg

vs1(t) = π sin (ωst) = Vs1 sin (ωst)

So model switch network output port

with voltage source of value vs1(t)

n = 1, 3, 5,...

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

13

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Model of switch network input port

Is1

NS

is(t)

1

vg

+

–

2

ig(t)

+

2

vs(t)

ω st

–

is(t)

1

ϕs

Switch network

Assume that switch network

output current is

i g(t) T = 2

Ts

s

i s(t) ≈ I s1 sin (ωst – ϕ s)

i g(τ)dτ

0

T /2

s

≈ 2

I s1 sin (ωsτ – ϕ s)dτ

Ts 0

2 I cos (ϕ )

=π

s1

s

It is desired to model the dc

component (average value)

of the switch network input

current.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

T s/2

14

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Switch network: equivalent circuit

+

vg

2I s1

π cos (ϕ s)

vs1(t) =

4Vg

π sin (ωst)

is1(t) =

Is1 sin (ωst – ϕs)

+

–

–

• Switch network converts dc to ac

• Dc components of input port waveforms are modeled

• Fundamental ac components of output port waveforms are modeled

• Model is power conservative: predicted average input and output

powers are equal

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

15

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.1.2 Modeling the rectifier and capacitive

filter networks

| iR(t) |

iR(t)

+

i(t)

+

vR(t)

v(t)

–

–

NR

Rectifier network

V

vR(t)

ωst

iR(t)

R

NF

Low-pass

filter

network

dc

load

–V

ϕR

Assume large output filter

capacitor, having small ripple.

If iR(t) is a sinusoid:

vR(t) is a square wave, having

zero crossings in phase with tank

output current iR(t).

Then vR(t) has the following

Fourier series:

∞

4V

1 sin (nω t – ϕ )

vR(t) = π

Σ

s

R

n

n = 1, 3, 5,

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

i R(t) = I R1 sin (ωst – ϕ R)

16

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Sinusoidal approximation: rectifier

Again, since tank responds only to fundamental components of applied

waveforms, harmonics in vR(t) can be neglected. vR(t) becomes

vR1(t) = 4V

π sin (ωst – ϕ R) = V R1 sin (ωst – ϕ R)

Actual waveforms

V

with harmonics ignored

4

πV

vR(t)

ωst

iR(t)

vR1(t)

fundamental

ωst

iR1(t)

vR1(t)

Re

Re = 82 R

π

i R1(t) =

–V

ϕR

ϕR

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

17

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Rectifier dc output port model

| iR(t) |

iR(t)

+

i(t)

+

vR(t)

v(t)

–

R

Output capacitor charge balance: dc

load current is equal to average

rectified tank output current

i R(t)

–

NR

NF

Rectifier network

V

Low-pass

filter

network

dc

load

vR(t)

Ts

=I

Hence

T s/2

I= 2

TS 0

2I

=π

R1

I R1 sin (ωst – ϕ R) dt

ωst

iR(t)

–V

ϕR

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

18

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Equivalent circuit of rectifier

iR1(t)

Rectifier input port:

+

Fundamental components of

current and voltage are

sinusoids that are in phase

vR1(t)

Hence rectifier presents a

resistive load to tank network

+

Re

–

2

π I R1

V

R

–

Re = 82 R

π

Effective resistance Re is

Re =

I

vR1(t) 8 V

=

i R(t) π 2 I

Rectifier equivalent circuit

With a resistive load R, this becomes

Re = 82 R = 0.8106R

π

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

19

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.1.3 Resonant tank network

Transfer function

H(s)

is1(t)

vs1(t)

+

–

Zi

iR1(t)

+

Resonant

network

vR1(t)

Re

–

Model of ac waveforms is now reduced to a linear circuit. Tank

network is excited by effective sinusoidal voltage (switch network

output port), and is load by effective resistive load (rectifier input port).

Can solve for transfer function via conventional linear circuit analysis.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

20

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Solution of tank network waveforms

Transfer function:

Transfer function

H(s)

vR1(s)

= H(s)

vs1(s)

is1(t)

Ratio of peak values of input and

output voltages:

VR1

= H(s)

Vs1

vs1(t)

+

–

Zi

iR1(t)

+

Resonant

network

vR1(t)

Re

–

s = jω s

Solution for tank output current:

i R(s) =

vR1(s) H(s)

=

v (s)

Re

Re s1

which has peak magnitude

H(s) s = jω

s

I R1 =

Vs1

Re

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

21

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.1.4 Solution of converter

voltage conversion ratio M = V/Vg

Transfer function

H(s)

is1(t)

Vg

+

–

+

–

iR1(t)

+

Resonant

network

Zi

vR1(t)

I

+

Re

2

π I R1

–

2I s1

π cos (ϕ s)

M= V = R

Vg

V

I

2

π

I

I R1

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

vs1(t) =

I R1

VR1

R

–

Re = 82 R

π

4Vg

π sin (ωst)

1

Re

V

H(s)

s = jω s

VR1

Vs1

22

4

π

Vs1

Vg

Eliminate Re:

V = H(s)

Vg

s = jω s

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Conversion ratio M

V = H(s)

Vg

s = jω s

So we have shown that the conversion ratio of a resonant converter,

having switch and rectifier networks as in previous slides, is equal to

the magnitude of the tank network transfer function. This transfer

function is evaluated with the tank loaded by the effective rectifier

input resistance Re.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

23

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.2 Examples

19.2.1 Series resonant converter

transfer function

H(s)

is(t)

+

dc

source +

–

vg(t)

L

+

Cs

vR(t)

vs(t)

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

v(t)

R

–

–

NS

switch network

i(t)

+

iR(t)

–

NT

resonant tank network

24

NR

NF

rectifier network low-pass dc

filter

load

network

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Model: series resonant converter

transfer function H(s)

L

is1(t)

Vg

+

–

+

–

C

Zi

iR1(t)

+

vR1(t)

I

+

Re

2

π I R1

V

–

2I s1

π cos (ϕ s)

vs1(t) =

4Vg

π sin (ωst)

Re

Re

=

Z i(s) R + sL + 1

e

sC

s

Q eω 0

=

2

s

1+

+ ωs

Q eω 0

0

H(s) =

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

series tank network

R

–

Re = 82 R

π

1 = 2π f

0

LC

L

R0 =

M = H( jωs) =

C

R

Qe = 0

Re

ω0 =

25

1

1+Q

2

e

1 –F

F

2

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Construction of Zi

|| Zi ||

1

ωC

ωL

f0

R0

Qe = R0 / Re

Re

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

26

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Construction of H

|| H ||

1

Qe = Re / R0

Re / R0

f0

C

ωR e

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

27

R /

e ω

L

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.2.2 Subharmonic modes of the SRC

switch

output

voltage

spectrum

Example: excitation of

tank by third harmonic of

switching frequency

fs

3fs

5fs

f

resonant

tank

response

Can now approximate vs(t)

by its third harmonic:

4Vg

vs(t) ≈ vsn(t) = nπ sin (nωst)

fs

3fs

5fs

f

tank

current

spectrum

Result of analysis:

H( jnωs)

V

M=

=

n

Vg

fs

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

3fs

5fs

28

f

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Subharmonic modes of SRC

M

1

1

3

1

5

etc.

1 f

5 0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

1 f

3 0

29

f0

fs

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.2.3 Parallel resonant dc-dc converter

is(t)

+

L

+

dc

source +

–

vg(t)

+

Cp

vs(t)

vR(t)

v(t)

R

–

–

NS

switch network

i(t)

iR(t)

–

NT

resonant tank network

NR

NF

rectifier network

low-pass filter

network

dc

load

Differs from series resonant converter as follows:

Different tank network

Rectifier is driven by sinusoidal voltage, and is connected to

inductive-input low-pass filter

Need a new model for rectifier and filter networks

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

30

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Model of uncontrolled rectifier

with inductive filter network

I

iR(t)

i(t)

iR(t)

+

+

ωst

vR(t)

vR(t)

v(t)

R

–

–

–I

NR

k

ϕR

4

πI

NF

rectifier network

low-pass filter

network

dc

load

iR1(t)

fundamental

Fundamental component of iR(t):

vR1(t)

i R1(t) = 4I

π sin (ωst – ϕ R)

ωst

vR1(t)

Re

2

Re = π R

8

i R1(t) =

ϕR

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

31

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Effective resistance Re

Again define

Re =

vR1(t) πVR1

=

4I

i R1(t)

In steady state, the dc output voltage V is equal to the average value

of | vR |:

V= 2

TS

T s/2

0

2V

VR1 sin (ωst – ϕ R) dt = π

R1

For a resistive load, V = IR. The effective resistance Re can then be

expressed

2

π

Re =

R = 1.2337R

8

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

32

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Equivalent circuit model of uncontrolled rectifier

with inductive filter network

iR1(t)

I

+

+

2V

π R1

Re

vR1(t)

–

+

–

V

R

–

2

π

Re =

R

8

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

33

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Equivalent circuit model

Parallel resonant dc-dc converter

transfer function H(s)

is1(t)

iR1(t)

+

L

Vg

+

–

+

–

Zi

C

vR1(t)

I

+

Re

2

π V R1

+

–

–

2I s1

π cos (ϕ s)

vs1(t) =

4Vg

π sin (ωst)

M = V = 82 H(s)

Vg π

parallel tank network

R

–

2

Re = π R

8

H(s) =

s = jω s

V

Z o(s)

sL

Z o(s) = sL || 1 || Re

sC

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

34

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Construction of Zo

|| Zo ||

Re

Qe = Re / R0

R0

f0

ωL

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

1

ωC

35

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Construction of H

|| H ||

Re / R0

Qe = Re / R0

1

f0

1

ω 2LC

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

36

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Dc conversion ratio of the PRC

Z o(s)

8

M= 2

sL

π

= 82

π

= 82

π 1+

s = jω s

1

s + s

ω0

Q eω 0

2

s = jω s

1

1–F

2 2

+ F

Qe

2

Re R

8

M= 2

=

π R0 R0

At resonance, this becomes

• PRC can step up the voltage, provided R > R0

• PRC can produce M approaching infinity, provided output current is

limited to value less than Vg / R0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

37

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.3 Exact characteristics of the

series and parallel resonant dc-dc converters

Define

f0

f0

< fs <

k+1

k

1 <F< 1

k+1

k

or

1 + ( – 1) k

ξ=k+

2

subharmonic index ξ

ξ=3

etc. k = 3

mode index k

ξ=1

k=2

f0 / 3

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

k=1

f0 / 2

k=0

fs

f0

38

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.3.1 Exact characteristics of the

series resonant converter

Q1

D1

Q3

L

C

D3

1:n

+

Vg

+

–

R

Q2

D2

Q4

V

–

D4

Normalized load voltage and current:

M= V

nVg

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

J=

39

InR0

Vg

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Continuous conduction mode, SRC

Tank current rings continuously for entire length of switching period

Waveforms for type k CCM, odd k :

vs(t)

Vg

– Vg

iL(t)

Q1

π

Q1

Q1

π

π

D1

ωst

D1

Q2

(k – 1) complete half-cycles

γ

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

40

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Series resonant converter

Waveforms for type k CCM, even k :

vs(t)

Vg

– Vg

iL(t)

Q1

D1

π

π

π

D1

Q1

ωst

D2

Q2

D1

k complete half-cycles

γ

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

41

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Exact steady-state solution, CCM

Series resonant converter

M ξ sin

2 2

2

γ

Jγ

1

+ 2

+ (– 1) k

2

ξ 2

2

cos

2

γ

=1

2

where

M= V

nVg

γ=

InR0

J=

Vg

ω0Ts π

=

F

2

• Output characteristic, i.e., the relation between M and J, is elliptical

• M is restricted to the range

0≤M ≤ 1

ξ

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

42

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Control-plane characteristics

For a resistive load, eliminate J and solve for M vs. γ

M=

ξ tan

4

2

Qγ

2

γ

Qγ

+

2

2

γ

ξ – cos

2

2

2

(–1) k+1 +

1+

Qγ

γ

ξ tan

+

2

2

4

2

Qγ

2

2

2

2

cos 2

γ

2

Exact, closed-form, valid for any CCM

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

43

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Discontinuous conduction mode

Type k DCM: during each half-switching-period, the tank rings for k

complete half-cycles. The output diodes then become reverse-biased

for the remainder of the half-switching-period.

vs(t)

Vg

– Vg

iL(t)

Q1

π

Q1

π

π

D1

ωst

X

Q2

k complete half-cycles

γ

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

44

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Steady-state solution: type k DCM, odd k

M=1

k

Conditions for operation in type k DCM, odd k :

f0

fs <

k

2(k – 1)

2(k + 1)

>J>

γ

γ

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

45

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Steady-state solution: type k DCM, even k

J = 2k

γ

Conditions for operation in type k DCM, even k :

f0

fs <

k

1 >M> 1

k–1

k+1

Ig = gV

gyrator model, SRC

operating in an even

DCM:

+

g

Vg

46

+

V

g = 2k

γR0

–

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Ig = gVg

–

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Control plane characteristics, SRC

1

Q = 0.2

0.9

Q = 0.2

0.8

0.35

M = V / Vg

0.7

0.5

0.35

0.6

0.75

0.5

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1

0.5

0.4

0.75

1

1.5

2

3.5

5

10

Q = 20

0

1.5

2

3.5

5

10

Q = 20

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2

F = f s / f0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

47

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Mode boundaries, SRC

k = 1 DCM

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.4

k = 3 DCM

0.3

k=4

DCM

0.2

etc.

0.1

k = 1 CCM

k = 0 CCM

k = 2 CCM

k = 2 DCM

0.5

k = 3 CCM

M

0.6

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2

F

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

48

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Output characteristics, SRC above resonance

6

F = 1.05

F = 1.07

5

F = 1.10

4

J

F = 1.01

3

F = 1.15

2

F = 1.30

1

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

M

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

49

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Output characteristics, SRC below resonance

F = 1.0

J

F = .93

F = .96

3

F = .90

2.5

F = .85

2

1.5

F = .75

4

π

k = 1 CCM

F = .5

2

π

k = 1 DCM

1

k = 2 DCM

F = .25

F = .1

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

M

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

50

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.3.2 Exact characteristics of

the parallel resonant converter

Q1

D1

Q3

L

1:n

D3

D7

Vg

+

–

C

R

D8

Q2

D2

Q4

+

D5

D6

V

–

D4

Normalized load voltage and current:

InR0

J=

Vg

M= V

nVg

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

51

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Parallel resonant converter in CCM

vs(t)

CCM closed-form solution

Vg

γ

sin (ϕ)

M = 2γ ϕ –

γ

cos

2

γ

ω0t

– Vg

iL(t)

– cos – 1 cos

γ

γ

+ J sin

2

2

for 0 < γ < π (

+ cos – 1 cos

γ

γ

+ J sin

2

2

for π < γ < 2π

ϕ=

vC(t)

vC(t)

V=

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

52

vC(t)

Ts

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Parallel resonant converter in DCM

vC(t)

Mode boundary

J > J crit(γ)

J < J crit(γ)

for DCM

for CCM

J crit(γ) = – 1 sin (γ) +

2

sin 2

γ

+ 1 sin 2 γ

2

4

DCM equations

ω0t

D5 D8

D6 D7

D6 D7

α

M C0 = 1 – cos (β)

J L0 = J + sin (β)

cos (α + β) – 2 cos (α) = –1

iL(t)

– sin (α + β) + 2 sin (α) + (δ – α) = 2J

β+δ=γ

M = 1 + 2γ (J – δ)

δ

D5 D8

D5 D8

D5 D8

D6 D7

D6 D7

β

γ

I

ω0t

(require iteration)

–I

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

53

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Output characteristics of the PRC

3.0

2.5

F = 0.51

0.6

2.0

0.7

J

1.5

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.0

0.5

1.5

1.3

1.2

1.1

F=2

0.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

M

Solid curves: CCM

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Shaded curves: DCM

54

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Control characteristics of the PRC

with resistive load

3.0

Q=5

2.5

M = V/Vg

2.0

1.5

Q=2

1.0

Q=1

Q = 0.5

0.5

Q = 0.2

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

fs /f0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

55

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.4 Soft switching

Soft switching can mitigate some of the mechanisms of switching loss

and possibly reduce the generation of EMI

Semiconductor devices are switched on or off at the zero crossing of

their voltage or current waveforms:

Zero-current switching: transistor turn-off transition occurs at zero

current. Zero-current switching eliminates the switching loss

caused by IGBT current tailing and by stray inductances. It can

also be used to commutate SCR’s.

Zero-voltage switching: transistor turn-on transition occurs at

zero voltage. Diodes may also operate with zero-voltage

switching. Zero-voltage switching eliminates the switching loss

induced by diode stored charge and device output capacitances.

Zero-voltage switching is usually preferred in modern converters.

Zero-voltage transition converters are modified PWM converters, in

which an inductor charges and discharges the device capacitances.

Zero-voltage switching is then obtained.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

56

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.4.1 Operation of the full bridge below

resonance: Zero-current switching

Series resonant converter example

+

Q1

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

+

iQ1(t) –

Vg

C

D3

+

–

vs(t)

Q2

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

Operation below resonance: input tank current leads voltage

Zero-current switching (ZCS) occurs

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

57

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Tank input impedance

Operation below

resonance: tank input

impedance Zi is

dominated by tank

capacitor.

∠Zi is positive, and

tank input current

leads tank input

voltage.

|| Zi ||

1

ωC

ωL

R0

Re

f0

Qe = R0 /Re

Zero crossing of the

tank input current

waveform is(t) occurs

before the zero

crossing of the voltage

vs(t).

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

58

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Switch network waveforms, below resonance

Zero-current switching

vs1(t)

Vg

vs(t)

+

t

Q1

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

C

D3

+

iQ1(t) –

– Vg

vs(t)

is(t)

Q2

Ts

+ tβ

2

tβ

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

t

Ts

2

Conduction sequence: Q1–D1–Q2–D2

Conducting

devices:

Q1

Q4

D1

D4

Q2

Q3

“Soft”

“Hard”

“Hard”

turn-on of turn-off of turn-on of

Q 1, Q 4

Q 2, Q 3

Q 1, Q 4

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Q1 is turned off during D1 conduction

interval, without loss

D2

D3

“Soft”

turn-off of

Q2, Q3

59

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

ZCS turn-on transition: hard switching

vds1(t)

Vg

+

Q1

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

+

iQ1(t) –

t

ids(t)

vs(t)

Q2

Ts

+ tβ

2

tβ

Conducting

devices:

C

D3

Q1

Q4

D1

D4

Ts

2

“Soft”

“Hard”

turn-on of turn-off of

Q1, Q4

Q1, Q4

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

t

Q2

Q3

D2

D3

Q1 turns on while D2 is conducting. Stored

charge of D2 and of semiconductor output

capacitances must be removed. Transistor

turn-on transition is identical to hardswitched PWM, and switching loss occurs.

60

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.4.2 Operation of the full bridge below

resonance: Zero-voltage switching

Series resonant converter example

+

Q1

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

+

iQ1(t) –

Vg

C

D3

+

–

vs(t)

Q2

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

Operation above resonance: input tank current lags voltage

Zero-voltage switching (ZVS) occurs

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

61

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Tank input impedance

Operation above

resonance: tank input

impedance Zi is

dominated by tank

inductor.

∠Zi is negative, and

tank input current lags

tank input voltage.

|| Zi ||

1

ωC

ωL

R0

Re

f0

Qe = R0 /Re

Zero crossing of the

tank input current

waveform is(t) occurs

after the zero crossing

of the voltage vs(t).

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

62

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Switch network waveforms, above resonance

Zero-voltage switching

vs1(t)

Vg

vs(t)

+

Q1

t

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

C

D3

+

iQ1(t) –

vs(t)

– Vg

is(t)

Q2

tα

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

t

Ts

2

Conduction sequence: D1–Q1–D2–Q2

Conducting D1

devices: D

4

“Soft”

turn-on of

Q1, Q4

Q1

Q4

D2

D3

Q1 is turned on during D1 conduction

interval, without loss

Q2

Q3

“Hard”

“Soft”

“Hard”

turn-off of turn-on of turn-off of

Q1, Q4

Q2, Q3

Q2, Q3

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

63

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

ZVS turn-off transition: hard switching?

vds1(t)

Vg

+

Q1

vds1(t)

D1

Q3

L

+

iQ1(t) –

t

C

D3

vs(t)

ids(t)

Q2

tα

Conducting D1

devices: D

4

“Soft”

turn-on of

Q1, Q4

Q1

Q4

Ts

2

D2

Q4

–

is(t)

D4

t

D2

D3

“Hard”

turn-off of

Q1, Q4

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Q2

Q3

When Q1 turns off, D2 must begin

conducting. Voltage across Q1 must

increase to Vg. Transistor turn-off

transition is identical to hard-switched

PWM. Switching loss may occur (but see

next slide).

64

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Soft switching at the ZVS turn-off transition

+

Q1

D1 C

leg

Vg

Q3

vds1(t)

Cleg

–

D3

is(t)

+

+

–

vs(t)

Q2

D2

Cleg

Cleg

D4

–

Q4

vds1(t)

Conducting

devices:

Turn off

Q1, Q4

X D2

D3

t

• Introduce delay

between turn-off of Q1

and turn-on of Q2.

So zero-voltage switching exhibits low

switching loss: losses due to diode

stored charge and device output

capacitances are eliminated.

Commutation

interval

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

to remainder

of converter

• Introduce small

capacitors Cleg across

each device (or use

device output

capacitances).

Tank current is(t) charges and

discharges Cleg. Turn-off transition

becomes lossless. During commutation

interval, no devices conduct.

Vg

Q1

Q4

L

65

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.4.3 The zero-voltage transition converter

Basic version based on full-bridge PWM buck converter

Q3

Q1

D1 C

leg

Vg

+

–

Cleg

ic(t)

Lc

D3

+

Q2

D2

Cleg

v2(t)

Cleg

D4

Q4

–

v2(t)

Vg

• Can obtain ZVS of all primaryside MOSFETs and diodes

Can turn on

Q1 at zero voltage

• Secondary-side diodes switch at

zero-current, with loss

• Phase-shift control

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Conducting

devices:

Q2

Turn off

Q2

66

X D1

t

Commutation

interval

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.5 Load-dependent properties

of resonant converters

Resonant inverter design objectives:

1. Operate with a specified load characteristic and range of operating

points

• With a nonlinear load, must properly match inverter output

characteristic to load characteristic

2. Obtain zero-voltage switching or zero-current switching

• Preferably, obtain these properties at all loads

• Could allow ZVS property to be lost at light load, if necessary

3. Minimize transistor currents and conduction losses

• To obtain good efficiency at light load, the transistor current should

scale proportionally to load current (in resonant converters, it often

doesn’t!)

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

67

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Topics of Discussion

Section 19.5

Inverter output i-v characteristics

Two theorems

• Dependence of transistor current on load current

• Dependence of zero-voltage/zero-current switching on load

resistance

• Simple, intuitive frequency-domain approach to design of resonant

converter

Examples and interpretation

• Series

• Parallel

• LCC

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

68

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Inverter output characteristics

transfer function

H(s)

Let H∞ be the open-circuit (RÕ∞)

transfer function:

vo( jω)

vi( jω)

io(t)

ii(t)

sinusoidal

source

+

vi(t) –

= H ∞( jω)

resonant

network

+

Zo v (t)

o

Zi

purely reactive

–

resistive

load

R

R→∞

and let Zo0 be the output impedance

(with vi Õ short-circuit). Then,

R

vo( jω) = H ∞( jω) vi( jω)

R + Z o0( jω)

This result can be rearranged to obtain

vo

2

+ io

2

Z o0

2

= H∞

2

vi

2

The output voltage magnitude is:

vo

2

= vov *o =

H∞

2

1 + Z o0

with

vi

2

Hence, at a given frequency, the

output characteristic (i.e., the relation

between ||vo|| and ||io||) of any

resonant inverter of this class is

elliptical.

2

/ R2

R = vo / io

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

69

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Inverter output characteristics

General resonant inverter

output characteristics are

elliptical, of the form

2

|| io ||

I sc =

vi

d

oa

l

ed ||

tch | Z o0

a

m =|

R

Z o0

2

vo

io

+ 2 =1

V 2oc

I sc

with

H∞

inverter output

characteristic

Voc = H ∞

I sc =

H∞

I sc

2

vi

Voc

2

vi

Voc = H ∞

vi

|| vo ||

Z o0

This result is valid provided that (i) the resonant network is purely reactive,

and (ii) the load is purely resistive.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

70

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Matching ellipse

to application requirements

Electrosurgical generator

|| io ||

|| io ||

50Ω

Electronic ballast

inverter characteristic

inverter characteristic

2A

40

ed

tch

ma

lamp characteristic

d

loa

2kV

|| vo ||

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

0W

71

|| vo ||

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Input impedance of the resonant tank network

Transfer function

H(s)

Z (s)

R

1 + o0

R

Z o0(s)

Z i(s) = Z i0(s)

= Z i∞(s)

Z o∞(s)

1+ R

1

+

Z o∞(s)

R

1+

where

v

Z i0 = i

ii

R→0

Z i∞ =

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

vi

ii

Effective

sinusoidal

source

+

vs1(t) –

72

Resonant

network

Zi

+

Zo

Purely reactive

Z o0 =

R→∞

i(t)

is(t)

vo

– io

vi → short circuit

Z o∞ =

v(t)

–

vo

– io

Effective

resistive

load

R

vi → open circuit

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Other relations

If the tank network is purely reactive,

then each of its impedances and

transfer functions have zero real

parts:

Z = – Z*

Reciprocity

Z i0 Z o0

=

Z i∞ Z o∞

i0

Z i∞ = – Z

Z o0 = – Z

Z o∞ = – Z

H∞ = – H

Tank transfer function

H(s) =

where

H ∞(s)

1+ R

Z o0

H∞ =

H∞

2

vo(s)

vi(s)

= Z o0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

i0

*

i∞

*

o0

*

o∞

*

∞

Hence, the input impedance

magnitude is

2

R

1+

Z o0

2

2

*

Z i = Z iZ i = Z i0

2

R

1+

Z o∞

R→∞

1 – 1

Z i0 Z i∞

73

2

2

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Zi0 and Zi∞ for 3 common inverters

Series

L

1

ωC

Cs

Z i0(s) = sL + 1

sC s

|| Zi∞ ||

s

ωL

Zo

Zi

|| Zi0 ||

Z i∞(s) = ∞

f

Parallel

1

ωC

L

Z i0(s) = sL

p

ωL

Zi

Cp

|| Zi∞ ||

Zo

Z i∞(s) = sL + 1

sC p

|| Zi0 ||

f

LCC

L

1

ωC +

s

Cs

1

ωC

Zi

Cp

Z i0(s) = sL + 1

sC s

p

1

ωC

s

Zo

ωL

|| Zi∞ ||

Z i∞(s) = sL + 1 + 1

sC p sC s

|| Zi0 ||

f

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

74

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

A Theorem relating transistor current variations

to load resistance R

Theorem 1: If the tank network is purely reactive, then its input impedance

|| Zi || is a monotonic function of the load resistance R.

l

l

l

l

So as the load resistance R varies from 0 to ∞, the resonant network

input impedance || Zi || varies monotonically from the short-circuit value

|| Zi0 || to the open-circuit value || Zi∞ ||.

The impedances || Zi∞ || and || Zi0 || are easy to construct.

If you want to minimize the circulating tank currents at light load,

maximize || Zi∞ ||.

Note: for many inverters, || Zi∞ || < || Zi0 || ! The no-load transistor current

is therefore greater than the short-circuit transistor current.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

75

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Proof of Theorem 1

Previously shown:

Zi

2

= Z i0

2

1+ R

Z o0

1+ R

Z o∞

á Differentiate:

2

d Zi

dR

2

á Derivative has roots at:

= 2 Z i0

2

2

–

1

Z o∞

2

R

1+

Z o∞

2

R

2

2

So the resonant network input

impedance is a monotonic function

of R, over the range 0 < R < ∞.

(i) R = 0

(ii) R = ∞

(iii) Z o0 = Z o∞ , or Z i0 = Z i∞

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

2

1

Z o0

In the special case || Zi0 || = || Zi∞ ||,

|| Zi || is independent of R.

76

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Example: || Zi || of LCC

|| Zi ||

1

ωC +

s

1

ωC

f0

f∞

p

rea

1

ωC

inc

rea

s

ing

R

ωL

inc

s

gR

sin

• for f < f m, || Zi || increases

with increasing R .

• for f > f m, || Zi || decreases

with increasing R .

• at a given frequency f, || Zi ||

is a monotonic function of R.

• It’s not necessary to draw

the entire plot: just construct

|| Zi0 || and || Zi∞ ||.

fm

f

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

77

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Discussion: LCC

|| Zi0 || and || Zi∞ || both represent

series resonant impedances,

whose Bode diagrams are easily

constructed.

|| Zi0 || and || Zi∞ || intersect at

frequency fm.

1

ωC +

s

|| Zi ||

LCC example

f0

1

ωC

f∞

p

ωL

1

ωC

s

|| Zi∞ ||

|| Zi0 ||

For f < fm

1

2π LC s

1

f∞ =

2π LC s||C p

1

fm =

2π LC s||2C p

f0 =

fm

then || Zi0 || < || Zi∞ || ; hence

transistor current decreases as

load current decreases

For f > fm

f

then || Zi0 || > || Zi∞ || ; hence

transistor current increases as

load current decreases, and

transistor current is greater

than or equal to short-circuit

current for all R

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

L

Zi∞

78

Cs

Cp

L

Zi0

Cs

Cp

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Discussion -series and parallel

Series

L

1

ωC

Cs

• No-load transistor current = 0, both above

and below resonance.

|| Zi∞ ||

s

ωL

Zo

Zi

|| Zi0 ||

f

Parallel

• Above resonance: no-load transistor current

is greater than short-circuit transistor

current. ZVS.

1

ωC

L

p

ωL

Zi

Cp

|| Zi∞ ||

Zo

|| Zi0 ||

f

LCC

L

1

ωC +

s

Cs

• ZCS below resonance, ZVS above

resonance

1

ωC

• Below resonance: no-load transistor current

is less than short-circuit current (for f <fm),

but determined by || Zi∞ ||. ZCS.

p

1

ωC

ωL

s

Zi

Cp

Zo

|| Zi∞ ||

|| Zi0 ||

f

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

79

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

A Theorem relating the ZVS/ZCS boundary to

load resistance R

Theorem 2: If the tank network is purely reactive, then the boundary between

zero-current switching and zero-voltage switching occurs when the load

resistance R is equal to the critical value Rcrit, given by

Rcrit = Z o0

– Z i∞

Z i0

It is assumed that zero-current switching (ZCS) occurs when the tank input

impedance is capacitive in nature, while zero-voltage switching (ZVS) occurs when

the tank is inductive in nature. This assumption gives a necessary but not sufficient

condition for ZVS when significant semiconductor output capacitance is present.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

80

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Proof of Theorem 2

Previously shown:

Z

1 + o0

R

Z i = Z i∞

Z

1 + o∞

R

If ZCS occurs when Zi is capacitive,

while ZVS occurs when Zi is

inductive, then the boundary is

determined by ∠Zi = 0. Hence, the

critical load Rcrit is the resistance

which causes the imaginary part of Zi

to be zero:

Note that Zi∞, Zo0, and Zo∞ have zero

real parts. Hence,

Z

1 + o0

Rcrit

Im Z i(Rcrit) = Im Z i∞ Re

Z

1 + o∞

Rcrit

1–

= Im Z i∞ Re

1+

Z o∞

2

R 2crit

Solution for Rcrit yields

Im Z i(Rcrit) = 0

Rcrit = Z o0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

Z o0Z o∞

R 2crit

81

– Z i∞

Z i0

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Discussion ÑTheorem 2

Rcrit = Z o0

l

l

l

l

l

– Z i∞

Z i0

Again, Zi∞, Zi0, and Zo0 are pure imaginary quantities.

If Zi∞ and Zi0 have the same phase (both inductive or both capacitive),

then there is no real solution for Rcrit.

Hence, if at a given frequency Zi∞ and Zi0 are both capacitive, then ZCS

occurs for all loads. If Zi∞ and Zi0 are both inductive, then ZVS occurs for

all loads.

If Zi∞ and Zi0 have opposite phase (one is capacitive and the other is

inductive), then there is a real solution for Rcrit. The boundary between

ZVS and ZCS operation is then given by R = Rcrit.

Note that R = || Zo0 || corresponds to operation at matched load with

maximum output power. The boundary is expressed in terms of this

matched load impedance, and the ratio Zi∞ / Zi0.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

82

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

LCC example

l

l

l

l

For f > f∞, ZVS occurs for all R.

For f < f0, ZCS occurs for all R.

For f0 < f < f∞, ZVS occurs for

R< Rcrit, and ZCS occurs for

R> Rcrit.

Note that R = || Zo0 || corresponds

to operation at matched load with

maximum output power. The

boundary is expressed in terms of

this matched load impedance,

and the ratio Zi∞ / Zi0.

|| Zi ||

1

ωC +

s

1

ωC

ZCS ZCS: R>Rcrit ZVS

for all R ZVS: R<Rcrit for all R

ωL

p

1

ωC

s

Z i∞

|| Zi0 ||

Z i0

|| Zi∞ ||

{

f1

fm

f

Rcrit = Z o0

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

f∞

f0

83

– Z i∞

Z i0

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

LCC example, continued

∠Zi

R

90˚

R=0

60˚

easi

incr

ZCS

30˚

ng R

0˚

R crit

||

||

-30˚

ZVS

Z o0

-60˚

R=∞

f0

fm

-90˚

f∞

Typical dependence of Rcrit and matched-load

impedance || Zo0 || on frequency f, LCC example.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

f

f0

84

f∞

Typical dependence of tank input impedance phase

vs. load R and frequency, LCC example.

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

19.6 Summary of Key Points

1.

2.

The sinusoidal approximation allows a great deal of insight to be

gained into the operation of resonant inverters and dc–dc converters.

The voltage conversion ratio of dc–dc resonant converters can be

directly related to the tank network transfer function. Other important

converter properties, such as the output characteristics, dependence

(or lack thereof) of transistor current on load current, and zero-voltageand zero-current-switching transitions, can also be understood using

this approximation. The approximation is accurate provided that the

effective Q–factor is sufficiently large, and provided that the switching

frequency is sufficiently close to resonance.

Simple equivalent circuits are derived, which represent the

fundamental components of the tank network waveforms, and the dc

components of the dc terminal waveforms.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

85

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Summary of key points

3.

4.

5.

Exact solutions of the ideal dc–dc series and parallel resonant

converters are listed here as well. These solutions correctly predict the

conversion ratios, for operation not only in the fundamental continuous

conduction mode, but in discontinuous and subharmonic modes as

well.

Zero-voltage switching mitigates the switching loss caused by diode

recovered charge and semiconductor device output capacitances.

When the objective is to minimize switching loss and EMI, it is

preferable to operate each MOSFET and diode with zero-voltage

switching.

Zero-current switching leads to natural commutation of SCRs, and can

also mitigate the switching loss due to current tailing in IGBTs.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

86

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion

Summary of key points

6. The input impedance magnitude || Zi ||, and hence also the transistor

current magnitude, are monotonic functions of the load resistance R.

The dependence of the transistor conduction loss on the load current

can be easily understood by simply plotting || Zi || in the limiting cases as

R Õ ∞ and as R Õ 0, or || Zi∞ || and || Zi0 ||.

7. The ZVS/ZCS boundary is also a simple function of Zi∞ and Zi0. If ZVS

occurs at open-circuit and at short-circuit, then ZVS occurs for all loads.

If ZVS occurs at short-circuit, and ZCS occurs at open-circuit, then ZVS

is obtained at matched load provided that || Zi∞ || > || Zi0 ||.

8. The output characteristics of all resonant inverters considered here are

elliptical, and are described completely by the open-circuit transfer

function magnitude || H∞ ||, and the output impedance || Zo0 ||. These

quantities can be chosen to match the output characteristics to the

application requirements.

Fundamentals of Power Electronics

87

Chapter 19: Resonant Conversion