Motivational Techniques and Skills for Health and Mental Health

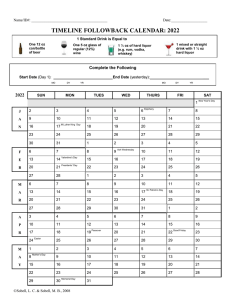

advertisement

Motivational Techniques and Skills 1 Motivational Techniques and Skills for Health and Mental Health Coaching/Counseling AFFIRMATIONS Examples of Affirmative Statements • “You showed a lot of [insert the person’s trait e.g. strength, determination] by doing that.” • “It’s clear that you’re really trying to change your [insert risky/problem/behavior].” • “In spite of what happened last week, you’re coming back today reflects that you’re concerned about changing your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior].” Rationale: Affirmations are statements made by practitioners in response to what people have said. They are used to recognize people’s strengths, successes, and efforts to change. They help to increase people’s confidence in their ability to change. Avoid statements that sound overly ingratiating or insincere (e.g., “ Wow, that’s incredible,” or “ That’s great, I knew you could do it!”). Use affirmations like salt, sparingly. ADVICE/FEEDBACK Examples of How to Provide Advice/Feedback If appropriate, start by asking permission to talk about the person’s behavior. Be prepared to provide them with relevant informational handouts. • “Do you mind if we spend a few minutes talking about…?” [Followed by] • “What do you know about…?” OR “What do you know about how your [insert a health behavior] affects your [insert health problem]?” [Followed by] • “Are you interested in learning more about…?” • “What do you know about the benefits of quitting smoking?” [Follow-­‐up with asking permission to talk about the person’s concern] • “So you said you are concerned about gaining weight if you stop smoking; how much do you think the average person gains in the first year after quitting?” For People Who Do Not Want Information • “I get the sense that you are not ready to change at this time. We can discuss this at a later time if you change your mind.” Rationale: People often have either little or incorrect information about their behaviors. Research has shown that telling people what to do does not work well. Most individuals prefer to be given choices in making decisions to change behaviors. By presenting information in a neutral and nonjudgmental manner empowers a person to make informed decisions about quitting or changing a risky/problem/unhealthy behavior. Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 2 Tips: When possible, focus on the positives of changing. (e.g., “ Within 20 minutes of stopping smoking the body begins a series of changes. Immediately a person’s blood pressure decreases. In 15 years after quitting, the risk of heart disease and death returns to nearly that of those who have never smoked.”) • Provide feedback that allows people to compare their behavior to national norms (e.g., % of people who have risky/problem/unhealthy behaviors). For example, “Where does your drinking fit in in relation to the national norms you see on the feedback page I just gave you?” • Avoid using scare tactics, lectures, or dire warnings as some people might pretend to agree in order to not be further attacked. ASKING PERMISSION Examples of Asking Permission • “Can we talk a bit about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” • “I noticed that you have [insert conditions]? Do you mind if we talk about how different lifestyles affect [insert condition]?” (Diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol use can be substituted for the word “lifestyles.”) Rationale: People are more likely to discuss change when respected and asked, than when being told to change NORMALIZING Examples of Normalizing • “A lot of people are concerned about changing their [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior].” • “Most people report both good and less good things about their [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior.” Rationale: Normalizing is intended to communicate that having difficulties changing is not uncommon for many people. OPEN-­‐ENDED QUESTIONS Examples of Open-­‐Ended Questions • “What makes you think it might be time for a change?” • “What brought you here today?” • “What happens when you [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” • “What was that like for you?” • “What’s different about (quitting smoking, improving your exercise, diet, etc.) this time?” Rationale: Open-­‐ended questions allow people to tell their stories and to do most of the talking. They give the practitioner opportunities to respond with reflections or summary statements that express empathy. Too many back-­‐to-­‐back close-­‐ended questions can feel like an interrogation (e.g., “How often do you overeat?” “How many years have you been smoking?”) Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 3 REFLECTIVE LISTENING Examples of Reflective Listening (generic stems) • “It sounds like…” • “It seems as if…” • “What I hear you saying…” • “I get the sense that…” • “I get the sense that this has been difficult…” Examples of Reflective Listening (specific reflections) • “It sounds like you are concerned about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior].” • “I get the sense that you want to change, and you have concerns about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior or topic].” • “What I hear you saying is that your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior] is really not much of a problem right now.” • “What do you think it might take for you to change in the future?” • “I get the feeling there is a lot of pressure on you to change, and you are not sure you can do it because of difficulties you had when you tried in the past.” Rationale: Reflective listening allows practitioners to carefully listen and then to paraphrase the person’s comments back (e.g., “It sounds like you are concerned about gaining weight if you quit smoking“. Goals of reflective listening include: (a) Building empathy, (b) Encouraging people to state their own reasons for change, and (c) Affirming that the practitioner understands what a person is feeling and doing (i.e., “It sounds like you are feeling upset at not meeting your goal.”). If the practitioner’s guess is wrong, the person usually says so (e. g. “No, I do want to quit, but I am concerned about withdrawal and weight gain.”). SUMMARIES Examples of Summaries • “It sounds like you are concerned about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior] because it is costing you many negative consequences. Where does that leave you?” • “On the one hand you feel you need to quit smoking for your health, but on the other hand that will probably mean not associating with your friends anymore. That doesn’t sound like an easy choice.” • “Over the past three months you have been talking about improving your diet and losing weight. It seems you have started to recognize the less good things about being overweight. And your girlfriend said she is leaving you if you don’t do something about your weight. It’s easy to understand why you are now committed to working on your weight.” Rationale: Summaries require that practitioners listen very carefully to what a person has said. Summaries are a good way to end a session (i.e., offer a summary of the entire session) as well as to move a talkative person on to the next topic. Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 4 CHANGE TALK Questions to Elicit Change Talk • “What makes you think you need to change?” • “What will happen if you don’t change?” • “What will be different if you (insert desired change: lose weight, improve eating, exercise, take your medications, etc.?)” • “What would be the good things about changing your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” • “Why do you think others are concerned about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” For People Having Difficulty Changing Focus is on being supportive as the person is struggling to change. • “How can I help you get past some of the difficulties you are experiencing?” • “If you were to decide to change, what would you have to do to make that happen?” For People Who Have Stated Little Desire For Change Ask the person to describe a possible extreme consequence if they do or don’t change. • “What is the BEST thing you could imagine that could result from changing?” • “If you don’t change, what is the WORST thing that might happen?” • “If you do change, how would your life be different from what it is today?” Rationale: Rather than lecturing or telling people the reasons why they should change, the practitioner gets people to state reasons for change that are personally important to them. Several studies show that change talk is associated with positive outcomes. PROS AND CONS OF CHANGE (Decisional Balancing) Examples of How to Use Pros and Cons of Change • “What are some of the good things about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” [The person answers] • “Okay, on the flipside, what are some of the less good things about your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” After the person discusses the good and less good things about their behavior, the practitioner can use a reflective, summary statement that allows people to talk about their ambivalence about changing. Rationale: Asking people to evaluate both the good and less good things about their actions helps them understand their ambivalence by seeing that (a) they get some benefits (pros) from their risky/problem/unhealthy behavior, and (b) that there will be some costs (cons) if they decide not to change their behavior. Such discussions are intended to help move people further along the readiness to change continuum. Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 5 READINESS TO CHANGE RULER Examples of How to Use a Readiness to Change Ruler 1___2___3___4___5___6___7___8___9___10 Not at all Ready Very Ready Practitioner: “On a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 is not at all ready to change and 10 is really ready to change where are you right now?” Person: “Seven.” Practitioner: “And where were you six months ago?” Person: “Two.” Practitioner: “So it sounds like you went from being not very ready to change your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior] to being much more ready to change.” • “How did you go from a ‘2’ 6 months ago to a ‘7’ now?” • “How do you feel about moving from a ‘2’ to a ‘7’ over the past 6 months?” • “What would it take to move a bit higher on the scale?” People with Lower Readiness to Change (e.g., answers decreased from a ‘5’ in the past to a ‘2’ now) • “So, it sounds like you went from being ambivalent to changing your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior] to no longer thinking you need to change your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior].” • “How did you go from a ‘5’ to a ‘2’?” • “What one thing do you think would have to happen to get you back to where you were before?” Rationale: Assessing readiness to change is critical. Readiness is not static; it can change from day to day. People are at different levels of motivation. If practitioners know where a person is on the readiness to change continuum they will be better prepared to work with them. Depending on where the person is on the Readiness to Change Ruler, the conversation may take different directions. The Ruler can also be used to have people give voice to how their readiness changed, what they need to do to change further, and how they confident they feel about changing right now. CONFIDENCE TO CHANGE Examples of How to Explore Confidence Ratings 1___2___3___4___5___6___7___8___9___10 Not at all Confident Very Confident • Practitioner: “On a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 is not at all confident and 10 is very confident to change how CONFIDENT are you right now that you could make this change?” • “What would it take to move from a [insert number] to a [higher number]?” • “What do you think you might do to increase your confidence about changing your [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]?” Rationale: Confidence ratings provide practitioners with information about how people view their ability Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 6 to make changes. The rating can be used to get people to give voice to what they need to do to increase their confidence. Tip: If a person reports a number of 7 or less, ask them “ What will it take to raise your number?” SUPPORTING CONFIDENCE TO CHANGE Examples of Statements Supporting Self-­‐Confidence Ask People about changes they made: • “It seems you’ve been working hard to quit smoking. That is different than before. How have you been able to do that?” • “So even though you haven’t quit, you have managed to cut down on your smoking. How were you able to do that?” Follow up with a question about how People feel about the changes they made: • “How do you feel about the changes you made?” • “How were you able to go from a [# 6 months ago] to a [# now]?” [The Person answers] “How do you feel about those changes?” Rationale: Making statements and asking questions about changes encourages people to recognize changes they have made. The objective is to increase their self-­‐ confidence that they can change. If a person’s confidence goes from a lower number (past) to a higher number (now), practitioners may follow-­‐up by asking how they were able to do that and how they feel about their change. FOR PEOPLE WHO ARE MAKING LITTLE PROGRESS Examples of How to Use a Paradoxical Statement Practitioner: “You have been trying to change [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior] for two months, but you are still doing [insert risky/problem/unhealthy behavior]. Maybe now is not the right time to change?” • “It sounds like you have a lot going on, and these priorities are competing with your efforts to change at this time.” For People Who Decide They Do Not Want to Change at This Time The practitioner can discuss with people the reasons why it has been difficult for them to change. Then the practitioner might suggest that person might want to take a short “vacation” from therapy (i.e., a few weeks) and think about whether this is really the best time to commit to changing. The practitioner can tell the person that he/she will call the person in a month to see where they are in terms of readiness to change. Rationale: Paradoxical statements about change are used to get people to argue for the importance of changing. It is hoped that the person would counter the practitioner statement with an argument that he/she wants to change (e.g., “No, I know I need to change, it’s just tough putting it into practice.”). Once a person states they do want to change, conversations can identify the reasons why progress has been slow up to now. If the person does not immediately argue for change, the practitioner can ask the person to think about this discussion between now and the next visit. Getting people to think about their behavior often serves to act as an eye-­‐opener. Reserve these statements for people who may not be aware that they are not making changes within a reasonable period of time. When using this approach, the practitioner must sound genuine and not sarcastic. “COLUMBO APPROACH” (Dealing with Discrepancies) Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Motivational Techniques and Skills 7 Using the Columbo Approach to Address Differences Between What People Say and Their Behavior • “On the one hand you’re coughing and having trouble breathing, and on the other hand you are saying cigarettes are not causing you any problems. *What do you think is contributing to your breathing difficulties?” • “Help me to understand, on the one hand you say you want to live to see your 12-­‐year old grow up and go to college, and yet you won’t take the medication your doctor prescribed for your diabetes. * How will that help you live to see your daughter grow up?” Note: *When using discrepancies try to end the statement on the side of change talk as people are more likely to elaborate on the last part of the statement. This approach takes its name from the behavior demonstrated by Peter Falk who starred in the 1970s television series Columbo. Rationale: The Colombo approach can be used to provide a curious inquiry without being judgmental or laying blame. This approach allows a practitioner to address discrepancies between what people say and their actual behavior without evoking defensiveness or resistance. By asking people to make sense of their discrepant information, they must give voice to, recognize, and resolve the discrepancies themselves. This approach evokes less resistance than a practitioner telling people that what they are doing does not make sense or is wrong. In addition, it eliminates the practitioner from sounding judgmental. Sobell and Sobell ©2013. Available online at http://www.nova.edu/gsc/online_files.html. This document is not to be copied or distributed without permission of the authors. For more information on motivational interviewing see Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2011). Group therapy with substance use disorders: A motivational cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.