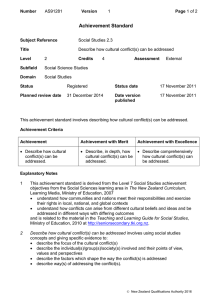

New Zealand Background Country Report

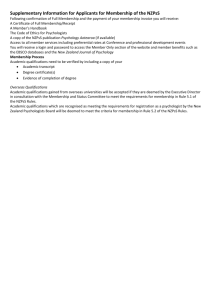

advertisement