The effective location of public library buildings.

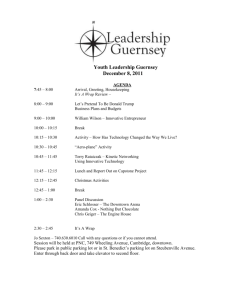

advertisement