Vocational Pathways: Using Industry Partnerships and

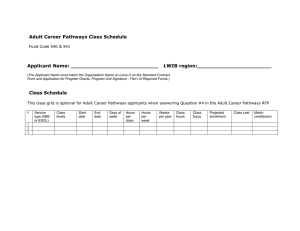

advertisement