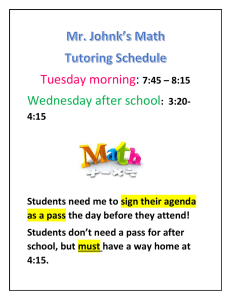

Helping young people to help themselves

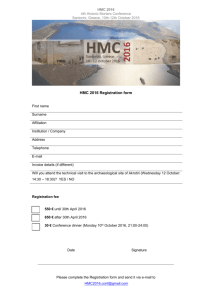

advertisement