A toy model for teaching the concept of EMF, terminal voltage and

advertisement

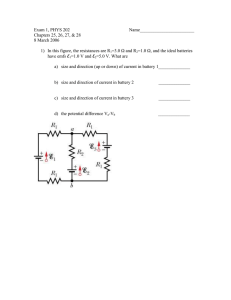

A toy model for teaching the concept of EMF, terminal voltage and internal resistance S. K. Foong Natural Sciences and Science Education, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 1, Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616 e-mail: seekit.foong@nie.edu.sg Abstract: The article considers a toy model for teaching the concepts of EMF, terminal voltage and internal resistance, especially the derivation of the equation V = ε − rI that relates these concepts. It is an extension of a mechanical model originally used for teaching foundational concepts such as the potential difference and emf. 1 Introduction The article considers a toy model for teaching the concept of EMF, terminal voltage and internal resistance, especially the derivation of the equation V = ε − rI that relates these concepts. It is an extension of the mechanical model innovatively used in Chabay and Sherwood book [1] when examining the roles of charges and fields in maintaining a steady current in a simple dc electric circuit and for teaching foundational concepts such as the potential difference and emf. The mechanical model has the advantage of focusing students’ attention on the development of physics concepts, not simultaneously requiring them to deal with the complications of the chemistry involved in a real battery. I found this feature useful in teaching introductory physics courses, and have thus extended the model to include a consideration of internal resistance in teaching a group of high ability Year 12 equivalent students. If it is within the grasp of the students, the inclusion of internal resistance is desirable as it explains various phenomena within the students’ experience such as the temperature rise of a shorted real battery and the dimming of the headlights when starting a car. The mechanical battery The mechanical battery consisting of a parallel plate capacitor of plate separation d and a conveyor belt operated by a motor to transport electrons across the plates, as shown in Figure 1. Without the motor-belt system working as an ``electron pump", as shown in Figure 2, the battery will soon be dead as the capacitor discharges. Figure 1. The Chabay and Sherwood’s mechanical battery in action (Ref. [1], pp. 207) Figure 2. With the conveyor belt removed, the mechanical battery will soon be dead as the capacitor discharges (Ref. [1], pp. 207) 2 To explain the working principles behind the mechanical battery, let’s suppose it is not connected to an external circuit and the capacitor is uncharged to begin with. When the motor is turned on, electrons are extracted from the left plate and transported to the right plate. We shall assume the conveyor belt is frictionless and massless to begin with. Let FC denote the Coulomb force exerted on an electron while it is being transported on the belt by the charged plates, and let FNC denotes the force exerted on the electron by the belt. Let EC denote the electric field in the capacitor, thus FC =eEC. Let the number of transported electron on the belt at any one time be N. The extracted electrons on the belt undergo acceleration at first because, with little charge on the plates, EC is small and so is FC, compared to FNC. As the charges on the plates built up, FC increases and when FC = FNC the motor cannot pump any more charge, and the plates are charged up as much as they can be by the motor. We have arrived at a static equilibrium situation, and there is no further motion of charges. See Figure 3 for an illustration. (Strictly speaking, when FC = FNC the charging continues because the motor-belt system continues operation due to inertia, but just as the negative plate gets charged up further FC becomes greater than FNC and the belt slows down. To avoid this problem, a sensor may be installed on the motor-belt system to switch it off once it slows down.) Figure 3. When FC = FNC the motor cannot pump any more charge, and the plates are charged up as much as they can be (Ref. [1], pp. 221) Extensions of the mechanical battery To assist the conceptual development of the students, one may imagine the conveyor belt is operated by a weight of mass M attached to one of the axles (eg. the axle on the right) in such a way that as the weight is allowed to fall, the axles of the conveyor belt is rotated as shown in Figure 4. This will yield an example for FNC, and also a formula for FNC in terms of adjustable parameters. This example allows the student to seek confirmation of his conceptual reasoning. Let the radius of the axle be R and assume the axles are massless and frictionless. At static equilibrium, by equating the counter-clockwise and clockwise torques, we have eECR=(Mg/N)R, or FNC=eEC=Mg/N, and EC=Mg/Ne. Substitute EC=Mg/Ne into the formula for charge on capacitor, namely Q=ε0 A EC, we obtain also Q=ε0 A Mg/Ne. 3 (a) (b) Figure 4. (a) Conveyor belt operated by a weight of mass M attached to the axle on the right. (b) Static equilibrium, axles stop rotating. At static equilibrium, the work done by the falling weight to move an electron from the positive plate to the negative plate is Mgd/N. Since EMF ε is defined as the work done per unit charge, thus ε= Mgd/Ne. Now suppose the charged battery is connected to a simple external circuit to light up a light bulb, and let the steady state current be I. At this steady state, the conveyor belt is moving at constant velocity v, which may be determined by the requirement that the belt must move the electrons fast enough to replenish the electrons on the negative plate. Let the N electrons on the belt be uniformly distributed over the length d, and thus the number of electrons reaching at the negative plate per second equals (N/d) v. Since every second the negative plate is losing I/e electrons, thus (N/d) v= I/e in order to maintain a constant current, that is v= Id . Ne (1) Extending the toy model to include internal resistance A real battery has internal resistance. To introduce such resistance into the mechanical battery, one may introduce friction or resistance into the conveyer belt system, and in my class I have assumed a friction that is proportional to the linear speed at the surface of the axles, due to say the surfaces of the axles rubbing on their support. Let's denote the total friction of both the axles as Ff , thus Ff = Gv , where G is the proportionality constant. Now again suppose the charged battery is connected to a simple external circuit to light up a light bulb, and let the steady state current be I. In steady state, the net torque is zero, therefore forces involved must balance, namely 4 Mg − NeE C − Gv = 0 . (2) Substituting for v= Id/Ne and rearranging terms, we have EC = Mg GdI − Ne N 2 e 2 (3) and multiplying Eq. (3) by d gives EC d = Mgd Gd 2 I − 2 2 Ne N e (4) Mgd is the work done per unit charge by the falling Ne weight and is therefore the emf. The factor Gd 2 / N 2 e 2 is the mechanical analogue of electrical resistance can be seen as follows. The electrical resistance of a resistor is defined by r = V/I, where I is the current flowing through the resistor, and V is the voltage drop, or the electrical work done per unit charge in crossing the resistor. The mechanical work done against the axle friction in moving the conveyor belt a distance d is Gvd, and the amount of charge transported is Ne, thus the mechanical work done per unit charge is Gvd/Ne. Therefore, the mechanical analogue of internal resistance of the mechanical battery may be defined by the mechanical work done per unit charge per unit current, or Obviously ECd is the terminal voltage V, and r= Gvd / Ne Gvd / Ne Gd 2 = = 2 2. I Nev / d N e (5) We wish to remark in passing that this mechanical analogue of electrical resistance helps to broaden the students’ perspective in interpretation of physics concepts. With internal resistance identified, Eq. (4) becomes V = ε − rI , (6) the standard equation relating the battery’s terminal voltage, EMF, internal resistance and the current flowing through it. My experience has shown that many students had difficulty understanding this equation. This derivation shows clearly how this equation is the consequence of energy conservation. Conclusion 5 We have constructed a toy model for teaching the concept of EMF, terminal voltage and internal resistance by extending the mechanical model used in Chabay and Sherwood book [1]. My experience has shown that pupils in my high ability Pre-U class appreciate the course materials, and it would be desirable to appropriately adapt the material to benefit a larger group of average students as well. Acknowledgement: I would like to thank the students of the University’s SM2 Program for their inquisitiveness and stimulating questions. References [1] Chabay R and Sherwood B 1995 Electric and Magnetic Interactions (John Wiley), pp. 206— 357. 6