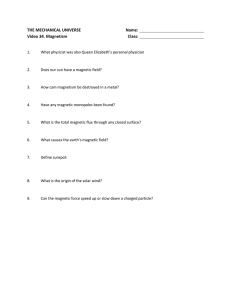

Chapter 9 Magnetic Forces, Materials, and Inductance

advertisement