the sparks` handbook

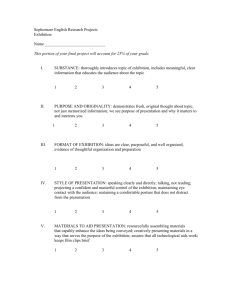

advertisement