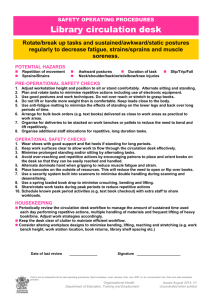

Manual Handling Code of Practice: Safety Guidelines

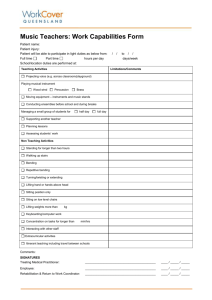

advertisement