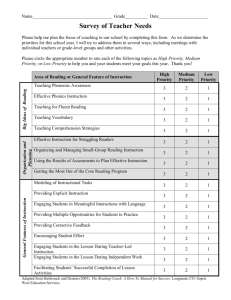

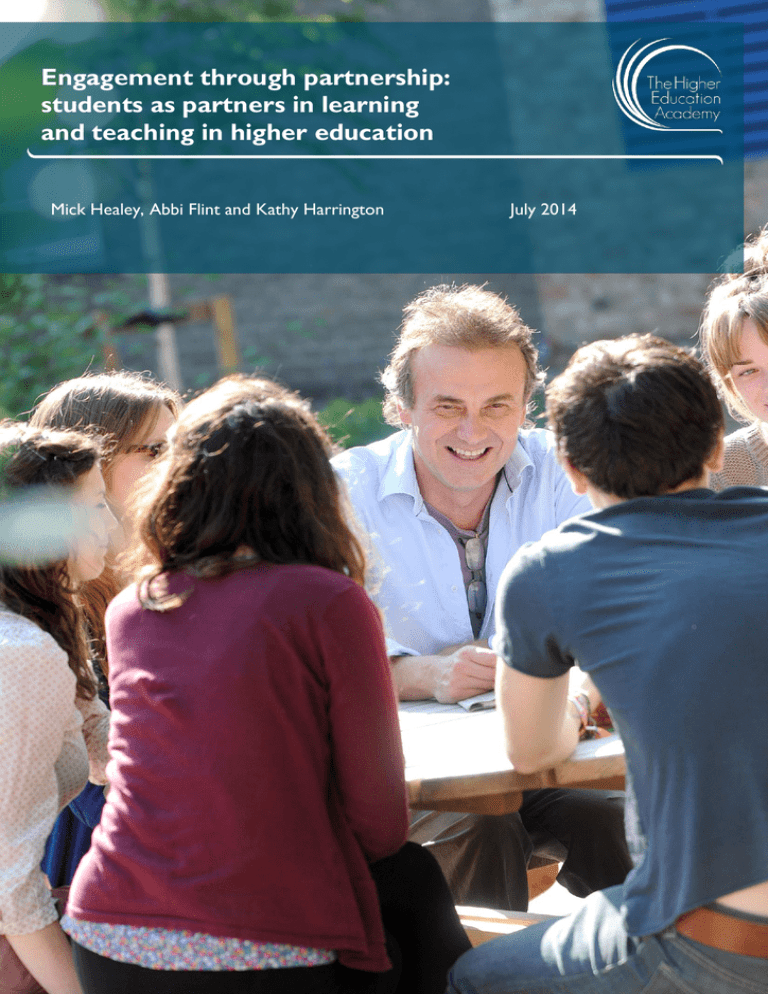

Engagement through partnership

advertisement