COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING: Engaging Students for Success

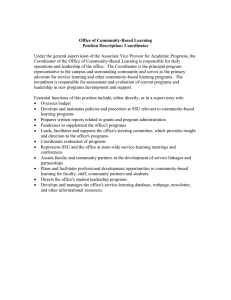

advertisement