LAW AND LAND DEVELOPMENT IN VERMONT A Practical Guide

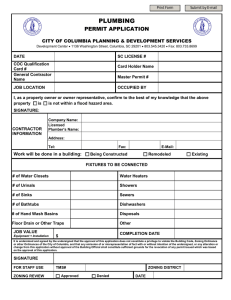

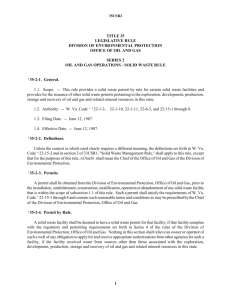

advertisement